“This school believes that crystal deposition is the primary step in the development of gouty tophi and therefore attribute tissue necrosis to the damaging effect of the crystals,” he said. “In opposition are other authors … who defend the idea that the tissue necrosis of the gouty lesion is the primary event, and the deposition of uric acid salts is secondary to this.”5

In his own work injecting urate crystals into rabbits, Dr. Freudweiler observed evidence of acute inflammation and tissue necrosis in those injected.5 Some other early research

also found inflammatory reactions resulting from the injection of crystalline uric acids or other forms of urates into living tissue.5 But much of this work fell into obscurity, and Dr. Garrod’s work was left unconfirmed.

Intervening Years

In the following years, the medical community did come to accept a pathophysiologic role between tophaceous gout and hyperuricemia. Salicylates, the first uricosuric agents when given in high doses, and then later agents, such as probenecid, could successfully lower serum urate and gradually dissolve tophaceous gout deposits.2,3

Through the 1950s, however, medical texts were noncommittal about the relationship between urates and the pathogenesis of acute inflammatory gouty attacks, and the mechanism of acute gouty arthritis was studied relatively little.2

It was well established by then that some, but not all, people with hyperuricemia suffered attacks of acute gouty arthritis. On the other hand, when solutions of non-crystallized sodium urate were injected into humans, this had not seemed to trigger a gout flare, nor did the administration of large doses of uric acid delivered intravenously.1 At the time, this was a primary point made by those arguing that urates played no role in triggering acute gouty flares.2

Modern Study of Gout

One might argue that the modern study of gout began in 1961, with work led by Daniel J. McCarty Jr., MD, then head of rheumatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.6,7 Using polarized light microscopy, McCarty et al. were able to show crystals of monosodium urate in gouty synovial fluid, often in the process of undergoing phagocytosis. These had been much more difficult to see via the standard light microscopy used previously.

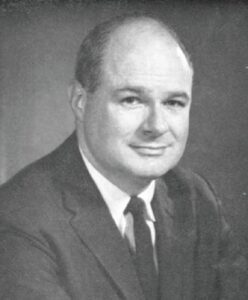

Dr. McCarty

The next year, two key complementary papers in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and The Lancet helped definitively establish the role of elevated serum urate and sodium urate crystals in triggering acute gout flares.1,2