Case study: You are asked to see a frail 78-year-old man with osteoarthritis and Parkinson’s disease who was recently discharged from the hospital after internal fixation of an intertrochanteric hip fracture sustained in a fall from standing height. The lowest T score on bone mineral density measurement is –1.7 at the total hip. Review of his laboratory results is notable for a serum calcium of 7.9 mg/dL, and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 40 mL/min. What would you do next?

Why Consider Bisphosphonates in the Hip-Fracture Population?

Hip fractures are one of the most dreaded results of osteoporosis, affecting one in six white women over the course of their lifetime and resulting in more deaths than breast cancer.1 For those individuals who survive, the consequences of a fracture include a high risk of mobility impairment, new functional dependence, and substantially elevated risk of hospitalization that persists for at least 12 months.2,3 Some of this morbidity is related to the occurrence of additional fractures after the initial event; prospective cohort studies have shown that one in five patients will suffer another fracture in the two years following their hip fracture, with nearly one-third of these being second hip fractures.4

Despite this high risk of additional osteoporotic fractures, fewer than 20% of older adults with hip fracture receive treatment for osteoporosis. This low secondary prevention rate holds true in nearly all settings and countries examined. While fragmentation of care and misaligned incentives have been implicated in the low treatment rate, surveys of providers caring for these frail older patients have also cited concerns that the high mortality rate after hip fracture may not allow sufficient time for the fracture-reduction benefit to accrue. Further, providers have been uncertain of the safety and efficacy of bisphosphonates in patients with multiple comorbidities and functional impairment, since most osteoporosis registration trials included a healthier, postmenopausal osteoporosis population.5 Finally, concerns have been raised about the impact of bisphosphonates on fracture healing in the hip-fracture population.

This article will summarize the evidence supporting the treatment of hip-fracture patients with bisphosphonates, including the impact of these agents on the occurrence of additional fractures, mortality, and safety endpoints. Practical and cost-effectiveness considerations will also be discussed.

Evidence Supporting Use of Bisphosphonates after Hip Fracture

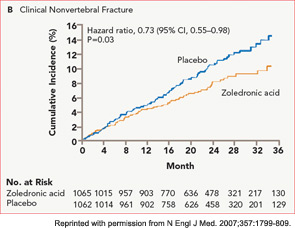

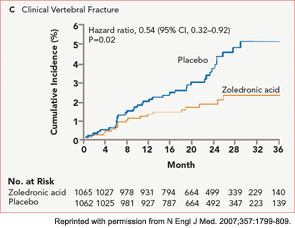

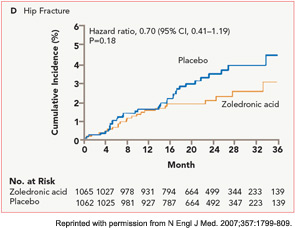

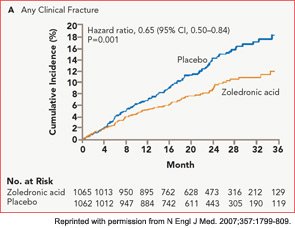

The HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial (HORIZON-RFT) was designed to determine the risks and benefits of bisphosphonate treatment in frail older adults with hip fracture. HORIZON-RFT was a randomized, controlled, double-blind study comparing zoledronic acid 5 mg IV yearly with a placebo. More than 2,100 patients were enrolled within 90 days of surgical repair of a low-trauma hip fracture, and were followed for up to three years for additional clinical fractures, bone mineral density (BMD), and safety endpoints including mortality (see Figure 1, above). Patients were enrolled from both community and institutional settings, but were ambulatory prior to the hip fracture. Other notable inclusion criteria were estimated GFR of greater than 30 mL/min, near-normal serum calcium levels, and inability or unwillingness to take an oral bisphosphonate. Because a large proportion of participants were found to be vitamin D insufficient, all participants received a loading dose of approximately 100,000 IU at least one week prior to the first dose of zoledronic acid, followed by daily oral calcium and vitamin D supplements. Patients were enrolled regardless of their baseline DXA, and 45% had T scores > –2.5.6

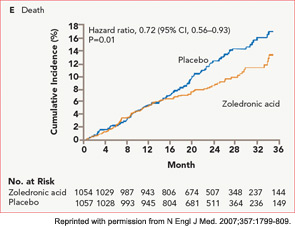

HORIZON-RFT showed that yearly zoledronic acid reduced the risk of subsequent clinical fractures after hip fracture by 35%, with comparable reductions in all fracture types, and across multiple subgroups of patients. BMD was significantly improved, as were quality-of-life measures related to pain and mobility.7 Fracture reduction benefits were seen in both community dwelling and institutionalized patients, and were also seen in those with baseline BMD above –2.5. Surprisingly, although mortality was included as a safety endpoint in the study, a significant 28% reduction in mortality was also observed in the treated patients; this was the first time a mortality benefit had been documented with an osteoporosis treatment.

Following the publication of the HORIZON-RFT trial results, additional studies have replicated the positive mortality findings among hip-fracture patients. In a cohort of 209 patients with hip fracture, treatment with oral bisphosphonate was associated with a significantly lower mortality, (6% reduction per month of treatment), even after adjusting for multiple confounders.8

Also consistent with the findings on lower mortality in treated patients, oral bisphosphonate use was associated with a 27% reduction in mortality among frail, institutionalized older adults in Australia.9 Thus, it appears that the antifracture efficacy of bisphosphonates is substantial in hip-fracture patients despite their competing comorbidities and lower life expectancies, and that measurable reductions in mortality are seen with oral and IV bisphosphonate treatment in this group.

Potential Mechanisms for Mortality Reduction

Because osteoporotic fractures themselves are associated with morbidity and mortality, it would seem logical that the lower rate of secondary fractures would explain the mortality reduction observed in HORIZON-RFT and subsequent studies. However, analyses of these data have shown that only 8% of the mortality reduction can be explained by prevention of secondary fractures.10 Potential mechanisms for the remaining mortality benefit remain controversial, but several intriguing hypotheses have been formulated.

It was noted in HORIZON-RFT that, while intervention and control patients had similar rates of common acute illnesses such as pneumonia or cardiovascular events, the risk of dying from these acute events was lower across most categories of illness in those patients who had received zoledronic acid. This pattern is consistent with a mechanism termed hormesis. In hormesis, an acute stressor (such as the acute phase reaction precipitated by intravenous bisphosphonate) renders an organism better able to withstand subsequent stressors. However, since the mortality benefit of bisphosphonates also appears to extend to oral agents, which have very short serum half-lives and no appreciable acute phase response, it is unclear how hormesis could be produced.

Significant treatment by disease interactions were observed in HORIZON-RFT for arrhythmias and pneumonia, with fewer treated patients dying of these illnesses.10

These findings raise the possibility that bisphosphonates may impact these illnesses through their documented immune system or antiinflammatory effects. Further work needs to be done to untangle these findings.

Fewer than 20% of older adults with hip fracture receive treatment for osteoporosis.

Practical and Safety Considerations for Bisphosphonate Use in Hip-Fracture Patients

Because of the higher burden of comorbidities in hip-fracture patients compared with postmenopausal osteoporosis populations, the concern for drug safety is heightened. In addition, there are logistical implications for initiating bisphosphonates in frail patients who may be transitioning between healthcare settings. The following section will consider fracture healing, vitamin D deficiency, renal safety, and the timing of infusion. We will discuss whether some patients are “too frail” to receive secondary fracture prevention after hip fracture.

Animal studies have suggested that bisphosphonates given in the acute fracture period might have an adverse impact on healing due to their suppression of bone turnover and therefore remodeling; the few human studies available have reported conflicting results, with oral bisphosphonates enhancing callus formation in Colles’ fractures, but doubling the risk of delayed healing of humeral fractures.11,12 HORIZON-RFT was therefore designed to prospectively identify and centrally adjudicate all potential cases of delayed hip-fracture healing. Similarly, potential cases of hip avascular necrosis were adjudicated as a potential harmful effect of giving zoledronic acid in the post-fracture period; femoral neck fractures may damage the single artery to the femoral head and precipitate a process similar to that hypothesized to lead to osteonecrosis of the jaw. While the rates of these complications in the HORIZON-RFT study were generally low, there was no difference in delayed fracture healing or avascular necrosis in those receiving zoledronic acid or placebo, regardless of the timing of infusion in relation to the hip-fracture repair.13 Thus, it appears that fracture healing complications are not a concern with bisphosphonates in hip-fracture populations.

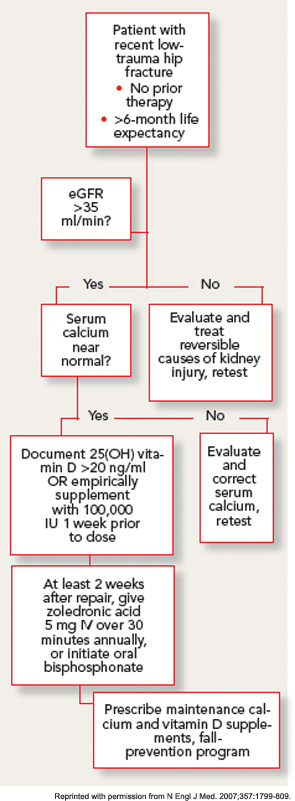

The prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency has been reported to exceed 60% in hip-fracture patients.14 This is a concern in initiating bisphosphonates, particularly intravenous formulations, because of the risk of precipitating clinically significant hypocalcemia.15 This risk may be especially problematic in older patients with concomitant renal impairment and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Measurement of 25(OH) vitamin D levels is recommended after fragility fracture, but results are often not immediately available, and then further delay accrues if the patient requires repletion prior to initiation of bisphosphonate. After initial experience in HORIZON-RFT demonstrated that most patients were vitamin D insufficient, and that waiting for 25(OH) vitamin D levels to return before proceeding with the protocol was not practical, the approach taken was to provide repletion dose for everyone with a single dose of approximately 100,000 IU vitamin D one week prior to the zoledronic acid infusion. The precise dose used and whether the supplement was D2 or D3 varied slightly across countries based on availability.

With this approach, no clinically significant cases of hypocalcemia were observed, and laboratory-detected hypocalcemia was quite rare and similar in both groups. No cases of vitamin D toxicity were found. Thus, for patients with normal calcium levels, an approach of universal repletion prior to bisphosphonate initiation appears safe. However, it is prudent to await further test results in patients with abnormal corrected serum calcium levels. While the serum levels of 25(OH) vitamin D at which bisphosphonates are safe has not been clearly determined in clinical studies, expert opinion holds that patients with serum levels above 20 ng/mL are unlikely to develop significant hypocalcemia.

GFR declines in most people with advancing age, and the prevalence of renal impairment is high in patients with hip fracture. Although most of the circulating serum bisphosphonate is deposited rapidly in the bone, nephrotoxicity has been documented with intravenous preparations, particularly in oncology populations receiving high dose therapy.16 Therefore, the label for oral and intravenous bisphosphonates excludes patients with GFR less than 30–35 mL/min, and renal safety has been scrutinized carefully with newer agents. No cases of clinically apparent acute kidney injury were observed in the zoledronic acid osteoporosis trials. Prospective laboratory studies in patients undergoing intravenous zoledronic acid therapy demonstrate a small acute decrease in GFR, which rapidly resolves, and no appreciable difference in renal function at one year.17 The infusion rate appears to be an important determinant of renal toxicity, thus minimum infusion times of 30 minutes have been recommended. It is prudent in older populations to document adequate hydration and baseline renal function with physical examination and laboratory testing prior to starting a bisphosphonate.

Patients in the post–hip fracture period usually have new mobility impairments and pain, and may be transitioning to a variety of healthcare settings over a short period. Therefore, minimizing the number of outpatient visits required to initiate osteoporosis treatment is an important goal. Although it would seem to be attractive to give the first dose of zoledronic acid during the hospitalization for hip-fracture surgery, there are several reasons that this is generally not practical. First, ensuring vitamin D sufficiency through laboratory testing or empiric repletion frequently takes longer than the average length of stay after hip fracture. In addition, post-hoc analysis of the HORIZON-RFT data strongly suggests that zoledronic acid has significantly lower efficacy on both BMD and fracture endpoints when given in the first two weeks after fracture.18This effect may occur because of the avid, preferential uptake of the drug at the fracture site, leaving less available for the rest of the skeleton.

While this effect may not be a problem for bisphosphonates dosed more frequently, it would seem important to wait at least two weeks after the fracture if yearly zoledronic acid therapy is planned. Unfortunately, current reimbursement discourages treatment for intravenous bisposphonates in rehabilitation or skilled nursing facilities, who must provide the drug out of a capitated payment. Coordination of the infusion with postoperative follow-up appointments may be possible. Initiating oral bisphosphonate is a simpler alternative therapy for those patients in whom infusions are not available or practical, although the direct evidence of their benefit is weaker. It is not necessary to wait for BMD measurement prior to initiating therapy, as treatment is indicated and effective regardless of baseline BMD.

It appears that the antifracture efficacy of bisphosphonates is substantial in hip-fracture patients despite their competing comorbidities and lower life expectancies.

Although HORIZON-RFT included an older population than is typical for osteoporosis trials, it is likely that the enrolled patients represented the healthiest subset of the hip-fracture population. Is there a group of patients who are “too frail” for treatment, in whom the risks and costs outweigh the benefits? Using a large Medicare sample, Curtis and colleagues demonstrated that, although the five-year risk of death after osteoporotic fracture in older adults usually exceeds the risk for second fracture across patient-demographic and fracture-type groups, the five-year risk for second fracture is also high, varying from a low of 13% to a high of 43%. Furthermore, the number of fracture patients who needed to be treated to prevent a second fracture was low, ranging from eight to 46 across all demographic groups.19

Although not specific to hip-fracture patients, a recent model examined the cost-effectiveness of five years of oral alendronate treatment in women with osteoporosis whose ages ranged from 50 to 90 years, and whose life expectancies varied from the highest to the lowest quartiles. Even in women at the oldest ages in the lowest quartile of life expectancy, which is likely representative of many hip-fracture patients, treatment was highly cost effective.20 While such analyses specific to the more expensive agents such as zoledronic acid are lacking in hip-fracture patients, given the efficacy of this agent in both fracture reduction and mortality, the results are likely to be similar. Therefore, our practice is to consider treatment in hip-fracture patients whom we judge to have a life expectancy of at least six months if such treatment is consistent with the patient’s goals of care.

Conclusion

Patients with hip fracture are an important and, until recently, overlooked population in which to consider bisphosphonate treatment. Solid data from clinical trials now show that such treatment is safe and effective in reducing both subsequent fractures and mortality, and it is likely to be cost effective in even the frailest patients. Since practical barriers to treatment can be significant it is important for hospital or provider groups to establish systems to ensure that eligible patients are offered treatment (see Figure 2).

Disclosures

Dr. Colón-Emeric is a consultant for Novartis, Amgen, and Daiichi Sankyo; receives research support from Novartis, Pfizer; and has a patent for the cardiovascular effects of bisphosphonates.

Dr. Colón-Emeric is associate professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center and associate director of the Durham VA Geriatrics Research Education and Clinical Center, Durham, N.C.

References

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. Facts and statistics about osteoporosis and its impact. www.iofbonehealth.org/facts-and-statistics.html. Updated January 2011.

- Fox K, Hawkes W, Hebel J, et al. Mobility after hip fracture predicts health outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:169-173.

- Zimmerman S, Chandler JM, Hawkes W, et al. Effect of fracture on the health care use of nursing home residents. Arch Int Med. 2002;162:1502-1508.

- Colón-Emeric C, Kuchibhatla M, et al. The contribution of hip fracture to risk of subsequent fractures: Data from two longitudinal studies. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:879-883.

- Colón-Emeric C, Casebeer L, Saag K, et al. Barriers to providing osteoporosis care in skilled nursing facilities: Perceptions of medical directors and directors of nursing. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5:361-366.

- Lyles K, Colón-Emeric C, Magaziner J, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fracture and mortality after hip fracture. New Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799-1809.

- Adachi J, Lyles K, Colón-Emeric C, et al. Zoledronic acid results in better health-related quality of life following hip fracture: The HORIZON–Recurrent Fracture Trial. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2539-2549.

- Beaupre L, Morrish D, Hanley D, et al. Oral bisphosphonates are associated with reduced mortality after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:983-991.

- Sambrook P, Cameron I, Chen J, et al. Oral bisphosphonates are associated with reduced mortality in frail older people: A prospective five-year study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2551-2556.

- Colón-Emeric CS, Mesenbrink P, Lyles KW, et al. Potential mediators of the mortality reduction with zoledronic acid after hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:91-97.

- Adolphson P, Abbaszadegan H, Boden H, Salemyr M, Henriques T. Clodronate increases mineralization of callus after Colles’ fracture: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial in 32 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:195-200.

- Solomon D, Hochberg M, Mogun H, Schneeweiss S. The relation between bisphosphonate use and non-union of fractures of the humerus in older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:895-901.

- Colón-Emeric C, Nordsletten L, et al. Association between timing of zoledronic acid infusion and hip fracture healing. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2329-2336.

- Pieper CF, Colon-Emetic C, Caminis J, et al. Distribution and correlates of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels in a sample of patients with hip fracture. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5: 335-340.

- Peter R, Mishra V, Fraser WD. Severe hypocalcaemia after being given intravenous bisphosphonate. BMJ. 2004;328:335-336.

- Lewiecki EM, Miller PD. Renal safety of intravenous bisphosphonates in the treatment of osteoporosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:663-672.

- Boonen S, Sellmeyer DE, Lippuner K, et al. Renal safety of annual zoledronic acid infusions in osteoporotic postmenopausal women. Kidney Int. 2008;74:641-648.

- Eriksen EF, Lyles KW, Colón-Emeric CS, et al. Antifracture efficacy and reduction of mortality in relation to timing of the first dose of zoledronic acid after hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1308-1313.

- Curtis JR, Arora T, Matthews RS, et al. Is withholding osteoporosis medication after fracture sometimes rational? A comparison of the risk for second fracture versus death. J Am Med Dirs Assoc. 2010;11:584-591.

- Pham AN, Datta SK, Weber TJ, Walter LC, Colón-Emeric CS. Cost-effectiveness of oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis at different ages and levels of life expectancy. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1642-1649.