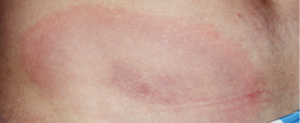

Erythema migrans rash in Lyme disease.

A team of healthcare practitioners and researchers, spearheaded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the ACR, has developed updated evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. The 2020 guidelines cover a wide variety of Lyme disease manifestations, including Lyme arthritis.

Linda Bockenstedt, MD, the Harold W. Jockers Professor of Medicine, section of rheumatology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., was the ACR lead on the multidisciplinary panel. “This comprehensive effort is critical for awareness,” says Dr. Bockenstedt. “Lyme disease is increasing in prevalence, and we know that only about 50% of the public living in endemic areas is taking preventive measures against tick-borne infections. Most people think about taking measures when they go into the woods, but you can [also] pick up a tick in your backyard or when pets bring them indoors.”

The panel, which included an additional 12 medical specialties and patients, used a standardized methodology for rating the certainty of the evidence and strength of the recommendations. Known as GRADE (the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation), this rigorous methodology has resulted in a robust document on the latest scientific and clinical information on Lyme disease available to healthcare practitioners.

Recommendations

Diagnostic testing strategy for Lyme arthritis

- Use serum antibody testing over polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture of blood or synovial fluid/tissue;

- In seropositive patients for whom the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis is being considered but treatment decisions require more definitive information, the panel recommends PCR applied to synovial fluid or tissue rather than Borrelia culture of those samples.

“Lyme disease can be associated with arthralgias and myalgia early on, but frank arthritis is a late manifestation of the infection,” says Dr. Bockenstedt. “Typically, patients present with arthritis many months after they were initially infected. Often, adults do not recall a previous tick bite or an earlier illness that is compatible with Lyme disease, such as a summer, viral-like syndrome or intermittent episodes of joint pain. They often present with a swollen knee, sometimes going to an orthopedic surgeon first, thinking they may have had a subacute athletic injury.”

Dr. Bockenstedt

Indeed, says Dr. Bockenstedt, with Lyme arthritis, the most common joint involved is the knee. “The knee is often very swollen, with less pain given the degree of swelling. It is rare to have more than two or three joints involved. Arthritis involving small joints of the hands and feet, as seen in rheumatoid arthritis, should not raise suspicion for Lyme disease.”

But testing can be tricky for practitioners, she says, due to the multiple testing options offered by commercial laboratories.

“Lyme arthritis would be extremely unusual in someone who doesn’t have positive Lyme IgG antibody testing,” continues Dr. Bockenstedt. “We [the panel] recommend following the two-tier method for diagnosing Lyme disease: screening with an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test first and then, if that is equivocal or positive, performing IgM and IgG immunoblots (Western blots).

“A common mistake is that the practitioner may order just the immunoblot assay and the results reveal positive IgM reactivity only or a single protein band on an IgG blot. By the time someone presents with Lyme arthritis, they most often have a strongly positive screening Lyme EIA and IgG immunoblot with multiple bands reactive. The guidelines also endorse the use of a modified two-tier Lyme assay, in which two different EIAs are performed sequentially or concurrently without immunoblots, which can eliminate some of this confusion over band interpretation.