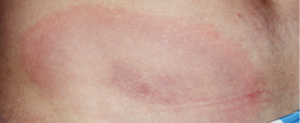

Erythema migrans rash in Lyme disease.

A team of healthcare practitioners and researchers, spearheaded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the ACR, has developed updated evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. The 2020 guidelines cover a wide variety of Lyme disease manifestations, including Lyme arthritis.

Linda Bockenstedt, MD, the Harold W. Jockers Professor of Medicine, section of rheumatology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., was the ACR lead on the multidisciplinary panel. “This comprehensive effort is critical for awareness,” says Dr. Bockenstedt. “Lyme disease is increasing in prevalence, and we know that only about 50% of the public living in endemic areas is taking preventive measures against tick-borne infections. Most people think about taking measures when they go into the woods, but you can [also] pick up a tick in your backyard or when pets bring them indoors.”

The panel, which included an additional 12 medical specialties and patients, used a standardized methodology for rating the certainty of the evidence and strength of the recommendations. Known as GRADE (the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation), this rigorous methodology has resulted in a robust document on the latest scientific and clinical information on Lyme disease available to healthcare practitioners.

Recommendations

Diagnostic testing strategy for Lyme arthritis

- Use serum antibody testing over polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture of blood or synovial fluid/tissue;

- In seropositive patients for whom the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis is being considered but treatment decisions require more definitive information, the panel recommends PCR applied to synovial fluid or tissue rather than Borrelia culture of those samples.

“Lyme disease can be associated with arthralgias and myalgia early on, but frank arthritis is a late manifestation of the infection,” says Dr. Bockenstedt. “Typically, patients present with arthritis many months after they were initially infected. Often, adults do not recall a previous tick bite or an earlier illness that is compatible with Lyme disease, such as a summer, viral-like syndrome or intermittent episodes of joint pain. They often present with a swollen knee, sometimes going to an orthopedic surgeon first, thinking they may have had a subacute athletic injury.”

Dr. Bockenstedt

Indeed, says Dr. Bockenstedt, with Lyme arthritis, the most common joint involved is the knee. “The knee is often very swollen, with less pain given the degree of swelling. It is rare to have more than two or three joints involved. Arthritis involving small joints of the hands and feet, as seen in rheumatoid arthritis, should not raise suspicion for Lyme disease.”

But testing can be tricky for practitioners, she says, due to the multiple testing options offered by commercial laboratories.

“Lyme arthritis would be extremely unusual in someone who doesn’t have positive Lyme IgG antibody testing,” continues Dr. Bockenstedt. “We [the panel] recommend following the two-tier method for diagnosing Lyme disease: screening with an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test first and then, if that is equivocal or positive, performing IgM and IgG immunoblots (Western blots).

“A common mistake is that the practitioner may order just the immunoblot assay and the results reveal positive IgM reactivity only or a single protein band on an IgG blot. By the time someone presents with Lyme arthritis, they most often have a strongly positive screening Lyme EIA and IgG immunoblot with multiple bands reactive. The guidelines also endorse the use of a modified two-tier Lyme assay, in which two different EIAs are performed sequentially or concurrently without immunoblots, which can eliminate some of this confusion over band interpretation.

‘Testing patients who have diffuse arthralgias, myalgias or fibromyalgia symptoms alone increases the potential for false positive results & inappropriate treatment.’ —Dr. Bockenstedt

“The ACR has previously recommended against routine screening for Lyme disease as a cause of musculoskeletal symptoms in the absence of a potential exposure to ticks that carry the Lyme bacteria or an appropriate physical exam. Testing patients who have diffuse arthralgias, myalgias or fibromyalgia symptoms alone increases the potential for false positive results and inappropriate treatment.”

Antibiotic regimens for the initial treatment of Lyme arthritis

- For patients with Lyme arthritis, use oral antibiotic therapy for 28 days.

For patients in whom Lyme arthritis has not completely resolved

- In patients with Lyme arthritis with partial response (e.g., mild residual joint swelling) after a first course of oral antibiotic, the panel makes no recommendation for a second course of antibiotic vs. observation. Consideration should be given to exclusion of other causes of joint swelling than Lyme arthritis, medication adherence, duration of arthritis prior to initial treatment, degree of synovial proliferation vs. joint swelling, patient preferences and cost. A second course of oral antibiotics for up to one month may be a reasonable alternative for patients in whom synovial proliferation is modest compared to joint swelling and for those who prefer repeating a course of oral antibiotics before considering intravenous antibiotics.

- In patients with Lyme arthritis with no or minimal response (i.e., moderate to severe joint swelling with minimal reduction of joint effusion) to an initial course of oral antibiotic, the panel suggests a two- to four-week course of IV ceftriaxone over a second course of oral antibiotics.

Treating post-antibiotic (previously known as antibiotic-refractory) Lyme arthritis

- In patients who have had no response or an inadequate response to one course of oral antibiotics and one course of IV antibiotics, the panel suggests referral to a rheumatologist or other trained specialist for consideration of the use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), biologic agents, intra-articular steroids or arthroscopic synovectomy. Antibiotic therapy for longer than eight weeks is not expected to provide additional benefit to patients with persistent arthritis if that treatment has included one course of intravenous antibiotics.

“In a small subset of patients treated for Lyme arthritis,” says Dr. Bockenstedt, “the swelling does not subside. In those instances, we don’t recommend continued treatment with antibiotics [because] this strategy has not proved to be effective. You can, however, treat these patients with medications used for rheumatoid and other forms of inflammatory arthritis, including DMARDs or biologics, with successful outcomes. These treatments do not lead to a recrudescence of infection. Current research indicates that persistent inflammation may be due to a failure to regulate the immune response after antibiotics have killed the Lyme bacteria.”

Pediatric Considerations

Dr. Zemel

Addressing the particular needs of children suspected of having Lyme arthritis was Lawrence Zemel, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, who led the panel’s pediatric subcommittee on arthritis management.

“When a child shows up in an [emergency department] or an office with one swollen joint,” says Dr. Zemel, “we have to parse out whether it is Lyme arthritis, septic arthritis or another form of acute arthritis. Septic arthritis is a medical emergency, so it is important to at least consider the possibility that this is what you’re dealing with.

“However, many practitioners rush to the diagnosis of septic arthritis and call an orthopedic surgeon. And, if the orthopedic surgeon has tunnel vision, then he or she [may] decide to intervene operatively, essentially overtreating

the condition.

“This happens fairly frequently [because] providers are not considering Lyme disease.”

Providing information on the main distinctions between septic arthritis and Lyme arthritis, Dr. Zemel notes, “Septic arthritis almost always involves a single joint, whereas Lyme arthritis may involve two to three different joints, sometimes sequentially. In addition, septic arthritis is almost always associated with fever. If you suspect septic arthritis, then aspirate the joint and examine the fluid. If the cell count is less than 70,000/uL, then septic arthritis is unlikely.”

Adding a dose of caution about antibiotics, he says, “A small segment of physicians tend to prescribe long-term antibiotics. With Lyme arthritis, however, neither children nor adults should be given more than two months of antibiotics.”

“In pediatric patients, if joint swelling remains after two months of antibiotics, intra-articular steroids can be helpful. Also note, when working up a child for Lyme arthritis, it is unnecessary to check for other co-infection tests unless the child has had a prolonged fever and/or other blood abnormalities.”

Elizabeth Hofheinz, MPH, MEd, is a freelance medical editor and writer based in the greater New Orleans area.

References

- Lantos PM, Rumbaugh J, Bockenstedt, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Jan;73(1):1–9.

- Lantos PM, Rumbaugh J, Bockenstedt, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Nov 29.