arka38 / SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

SAN DIEGO—Recent research tells us more about giant cell arteritis (GCA) to help rheumatologists more accurately diagnose and effectively treat patients with this type of vasculitis. On Nov. 6 at the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, three experts explored the latest findings on GCA pathogenesis, diagnostic approaches, imaging modalities and growing treatment options.

GCA: What’s Really Happening?

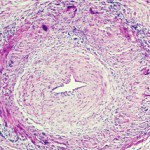

GCA is a granulomatous, large-vessel vasculitis that usually affects patients after 50, and women more often than men. GCA may affect the aorta and the smaller, second to fifth aortic branches, particularly the temporal artery, said Cornelia Weyand, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at Stanford University’s Vasculitis Research Center.

Immune privilege usually spares the aorta and its branches from inflammatory attacks, but in GCA, that pact is broken, she said. Patients may have aortic aneurysm, stenosis or occlusion in the aortic branches, tissue ischemia and constitutional symptoms that muscle pain, or polymyalgia rheumatica, as well as malaise, anemia, thrombocytosis, failure to thrive and, sometimes, fever.

GCA has both vascular and extravascular components. In the extravascular phase, innate immune cells like monocytes and neutrophils are triggered, and innate, pro-inflammatory cytokines are released. There is an induction of hepatic acute phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein, mannose-binding protein, ferritin and others. This may result in an inflammatory amplification loop.

“We need to understand the role of hepatic acute phase proteins in GCA and polymyalgia rheumatica, and we need to know what they do in the disease process. Right now, we do not know,” Dr. Weyand said.

Unanswered Questions

Tocilizumab, an IL-6 inhibitor, is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat GCA, but unanswered questions, including whether biomarkers for disease activity are lost after therapy blocks IL-6 and if the tissue-protective functions of acute phase proteins are also blocked by treatment, are important for GCA patients, said Dr. Weyand.

In GCA, T cells, dendritic cells and macrophages form granulomatous lesions inside the vessel walls. CT angiography and magnetic-resonance angiography (MRA) help reveal the degree of disease and which arteries are involved. Disease tends to go into the aortic branches in a symmetrical pattern. As occlusion occurs, blocking off blood flow, blood tends to be rerouted to other vessels. Patients form aneurysms when disease leads to vessel destruction in the aorta, requiring surgical repair.

“We know that the disease leads to dissection, which we can rapidly diagnose. We know that when it dissects, it does so between the adventitia and the media, and forms a dissection lesion,” which can be fatal without intervention, Dr. Weyand showed. “So how does this vasculitic lesion come about? And how is this lesion connected to the extravascular component of disease? The GCA lesion has two major pathomechanisms. It has intimal hyperplasia and intimal myofibroblast proliferation that leads to the occlusion of the lumen. And it has neo-angiogenesis that sits mostly in the adventitia, and that’s what we capture when we image these patients.”