Note: Updated May 2, 2018, to correct a link in the reference section. The error was introduced in editing.

A 44-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the outpatient rheumatology clinic that had followed her for several years for rheumatoid arthritis. She was compliant with her regimen of hydroxychloroquine, etanercept and salsalate. Her chief complaint was worsening pain in her left wrist with constant numbness and tingling and intermittent burning in the hand, particularly the first three-and-a-half fingers. Pain was worse at night. She had previously undergone successful carpal tunnel injections for this pain. She was wearing her splint nightly. Due to pain recurrence and severity, she had been recently referred to a hand surgeon for evaluation.

At this office visit, the physical examination included positive Tinel’s and Phalen’s tests on the affected side. Strength of the first digit was mildly diminished. She requested another injection to give her temporary relief while awaiting the orthopedic appointment. Using accepted topographical landmarks and targeting an area to the ulnar side of the median nerve, two attempts were made for perineural corticosteroid injection into her left carpal tunnel. The patient described severe paresthesia in her hand immediately upon needle insertion on both attempts. The procedure was terminated, and she was referred for sonographic evaluation and ultrasound-guided injection.

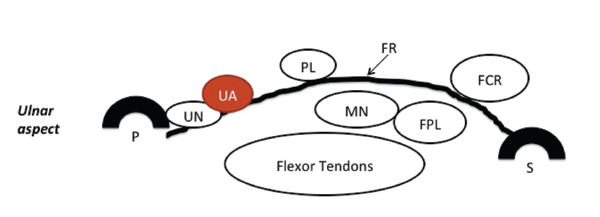

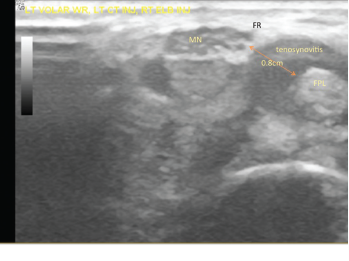

Ultrasound (US) revealed an enlarged, hypoechoic median nerve that had lost echotexture. Cross-sectional measurement of the median nerve at the wrist and forearm revealed the wrist to forearm ratio (WFR) quotient was 2.1; the median nerve had swollen to more than twice its normal size proximal to compression in the carpal tunnel. The swollen median nerve had a cross-sectional area (CSA) of 11 sq. mm.1 A notch sign, or abrupt compression of the median nerve, was noted. The US also identified significant noncompressible tenosynovitis of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL), displacing the median nerve in an ulnar direction directly in the needle path of the previous injection attempts. Power Doppler was positive surrounding the tendon. The flexor retinaculum (FR, also known as the transverse carpal ligament, or TCL) located just superficial to the median nerve had a normal sonographic appearance. (See Figure 1, for a schematic of normal carpal tunnel anatomy, and Figure 2, for this patient’s left volar wrist ultrasound, transverse view.)

An ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection of the FPL tendon sheath on the radial aspect of the median nerve (rather than the usual ulnar side with non-US-guided injections) resulted in dramatic reduction of the tenosynovitis and marked improvement of all symptoms. The medication regimen for her rheumatoid arthritis was then changed due to the suboptimal control of the disease process as indicated by the extensive tenosynovitis. In addition, it was appreciated that with even severe active tenosynovitis, successful treatment of the median nerve compression could occur with medical rather than surgical intervention.

Figure 1: A schematic of normal carpal tunnel anatomy. FR = flexor retinaculum; PL = palmaris longus tendon; FCR = flexor carpi radialis tendon; FPL = flexor pollicis longus tendon; MN = median nerve; UA = ulnar artery; UN = ulnar nerve; P = pisiform bone; S = scaphoid bone. Reprinted with permission from Greenberg MH. Manual of musculoskeletal ultrasound protocols (2018).

The patient has remained asymptomatic since the injection was performed, and the anti-rheumatic medical regimen was intensified more than eight months ago.

Discussion

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) results from any cause that increases pressure within the carpal tunnel, including enlargement of any of the nine flexor tendons or their coverings that pass through it (e.g., inflammation of the synovial sheaths). The median nerve is the most sensitive structure in the tunnel, supplying the first three-and-a-half digits. Compression of the median nerve may cause paresthesia, hypoesthesia, anesthesia or forearm/wrist/hand pain, and it can progress to loss of finger strength.2 The prevalence of CTS in the general population as defined by clinical evaluation and electrophysiological studies (EPS) measures 2.7%.1

Figure 2: The patient’s left volar wrist ultrasound, transverse view (MN = median nerve; FPL = flexor pollicis longus; FR = flexor retinaculum).

Multiple risk factors may affect the median nerve separately or in concert, including occupational or other causes of excessive wrist flexion, using vibrating tools, trauma, tenosynovitis (due to rheumatoid arthritis, other connective tissue diseases, spondyloathropathy, sarcoidosis or CPPD), female gender, obesity, amyloid, hypothyroid, pregnancy, a congenitally small carpal tunnel, aberrant structures within the carpal tunnel (e.g., a ganglion cyst, a neoplasm, gouty tophus, a lipoma, accessory muscles, a bifid median nerve, a persistent median artery, osteoarthritis, an aberrant bone), diabetes, acromegaly, use of aromatase inhibitors and genetic predisposition.3

Unilateral or bilateral CTS may be a presenting symptom in rheumatoid arthritis, and it may occur anytime during the disease course, particularly with suboptimal control of synovitis. The likelihood of having CTS is increased among patients with rheumatoid arthritis.4

CTS diagnosis occurs clinically. A typical history features painful paresthesia involving some or all of the first three-and-a-half fingers, and may include decreased sensation and hand weakness. Pain may radiate retrograde into the forearm and occasionally to the shoulder. Pain is often worse at night. A physical exam may demonstrate objective hypoesthesia, hand weakness, positive Tinel’s and/or Phalen’s signs, and thenar atrophy.

Electrophysiological studies (EPS) are corroborative if abnormal.5 However, EPS may be completely normal in 10–15% of clinical CTS cases.6 To complicate matters, one study found the false positive rate to be 18%.7

Sonography offers both qualitative and quantitative criteria to support the presence of CTS. Qualitatively, the median nerve may become hypoechoic and lose normal nerve echotexture.1 There may be swelling of the nerve proximal to the compression, and flattening of the nerve within a compression area. The abrupt flattening of the nerve is termed the “notch sign.”8

Various numeric sonographic criteria for CTS have been proposed, including direct measurement of CSA of the enlarged median nerve, comparison of CSA of the enlarged median nerve to the value in the forearm (i.e., the wrist-to-forearm ratio, or WFR), and the degree of palmar bowing of the flexor retinaculum.9-11

But how accurate is US in diagnosing CTS? A 2012 evidence-based guideline reviewed the four highest-quality studies up until May 2011 and determined the sensitivity of CTS diagnosis by US ranged from 65–97%, with accuracy ranging from 79–97%.5,12 These studies relied on median nerve CSA with the cut-off ranging from 8.5–10 mm2.

The conclusion: Based on Class I and Class II evidence, US measurement of median nerve CSA at the wrist is accurate and may be offered as a diagnostic test for CTS (Level A).12

What about Electrophysiological Studies?

Comparing US to EPS for CTS diagnosis may not be fair, because US delineates nerve structure and EPS looks at nerve function. In multiple studies, US and EPS featured fairly good correlation, although US correlated less well for mild CTS.13-16 We need further studies, though, before an abnormal US carries the same weight as an abnormal EPS in confirming CTS diagnosis.

What about patients with clinical CTS and negative EPS? As previously described, one study found completely normal EPS in 10–15% of cases of clinical CTS, and another study found 25% of CTS patients had normal EPS.6,17 A third study looked at 319 patients with a clinical diagnosis of CTS in whom 59 had normal EPS. US was performed on those 59 patients and compared with normal controls. US confirmed CTS in 18 of the EPS-negative 59 patients (i.e., about 30%).

The conclusion: US may be useful in diagnosing CTS in EPS-negative patients.18

How Do Orthopedists View US Diagnosis?

Not with any consensus. An evidence-based Level III meta-analysis of 19 articles (with a total of 3,131 wrists) published in an orthopedic journal in 2010 described US sensitivity and specificity of 77.6% and 86.8%, respectively. The authors suggested US, although not as sensitive or specific as EPS, may be a feasible alternative to EPS as a first-line confirmatory test.19 However, the February 2016 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ CTS management guidelines support not routinely using US for the diagnosis of CTS due to limited evidence.20

Ultrasound evaluation may identify the etiology of median nerve impingement by recognizing structural signs, such as severe tenosynovitis, bifid median nerve, a persistent median artery, a ganglion cyst, a neoplasm, a lipoma, accessory muscles and calcium/uric acid/amyloid deposits. US may also demonstrate a vastly swollen median nerve, which increases the probability of injury from injection without US guidance.21

Tenosynovitis appears as a hypoechoic halo surrounding a tendon due to either thickening of the tenosynovium, fluid accumulation or both. Compression with the transducer to look for fluid displacement may help differentiate tenosynovitis from effusion.

In our clinic, we routinely perform an evaluation of the ulnar nerve in the ulnar canal because injury to the deep (motor) branch may cause hand weakness (including the first digit) and potentially mimic median neuropathy.

Carpal Tunnel Treatment?

Treatment of CTS includes risk factor mitigation, cock-up splints to prevent night-time wrist flexion, medication to treat inflammation, corticosteroids orally or by injection to mitigate inflammation, surgical decompression with transection of the TCL and removal of offending structures, such as cysts.

When injection is an option, US evaluation has been proved to increase the efficacy and safety of carpal tunnel injection and may help direct the optimal injection location.22 The normal anatomy of the carpal tunnel contents may be distorted due to disease process. Ultrasound can identify anatomic alteration, thereby preventing further damage to the median nerve. As seen with our patient, blind injection using usual topographic landmarks risked impaling the median nerve. Ultrasound was necessary to visualize significant FPL tenosynovitis that resulted in migration of the median nerve to a distinctly abnormal position, one that would subject it to damage with a topographic landmark-guided injection.

By delineating the etiology of the CTS, US may inform overall treatment decisions. There’s an opportunity for conservative treatment when US reveals the presence of significant tenosynovitis causing median nerve compression, as in our case. You can target tenosynovitis with a combination of medication directed at the underlying disease process (rheumatoid arthritis, in our patient’s case) as well as US-guided injections directly into the area or areas of flexor tenosynovitis that appear to be compressing the median nerve. We also recommended continued use of cock-up splints at night in our case.

US may also prove useful after surgery because surgery doesn’t always alleviate symptoms. Continued or recurrent symptoms may be due to iatrogenic nerve injury, incomplete TCL release, perineural fibrosis or severe presurgical damage to the median nerve.23 Ultrasound’s capacity to visualize these complications may prove useful in delineating the cause of persistent symptoms after surgery.

Conclusion

Ultrasound has become an important tool for CTS evaluation. This inexpensive and noninvasive technique offers criteria to confirm a clinical diagnosis, and it demonstrates morphology that helps avoid treatment pitfalls.

CTS remains primarily a clinical diagnosis. Ultrasound and EPS are confirmatory studies that complement each other because the former modality provides anatomic information, while the latter assesses function. Use of either depends upon availability and the patient’s specific clinical needs.

Ultrasound may also have a place in evaluating EPS-negative patients with compelling symptoms and signs of CTS. It’s clearly useful for evaluating structural concerns that may be precipitating median neuropathy within the carpal tunnel, as well as determining the cause of continued symptoms following surgery. As our case illustrates, direct visualization of the cause of compressive median neuropathy may prove essential to guide treatment.

As Goethe once said, “One only sees what one looks for.” It may be time to start looking.

Mark H. Greenberg, MD, RMSK, RhMSUS, He did his rheumatology fellowship at the Albert Einstein-Montefiore Medical Center in The Bronx, New York. He is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group in Columbia, S.C.

Mark H. Greenberg, MD, RMSK, RhMSUS, He did his rheumatology fellowship at the Albert Einstein-Montefiore Medical Center in The Bronx, New York. He is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group in Columbia, S.C.

Julian Greer received her BS in exercise science from the University of South Carolina. She is a third-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine.

Julian Greer received her BS in exercise science from the University of South Carolina. She is a third-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine.

James W. Fant Jr., MD, completed his rheumatology fellowship at Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. He is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and director of the Rheumatology Division at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group in Columbia, S.C.

James W. Fant Jr., MD, completed his rheumatology fellowship at Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. He is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and director of the Rheumatology Division at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group in Columbia, S.C.

References

- Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, et al. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA. 1999 Jul 14;282(2):153–158.

- Biachi S, Martinoli C. (2007). Ultrasound of the Musculoskeletal System. 458–467. Springer.

- Kothari MJ, Shefner JM, Dashe JF. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Etiology and epidemiology. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Aug 25, 2017.

- Shiri R. Arthritis as a risk factor for carpal tunnel syndrome: A meta-analysis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016 Oct;45(5):339–346.

- Kothari MJ, Shefner JM, Dashe JF. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Mar 9, 2017.

- Werner RA, Andary M. Electrodiagnostic evaluation of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2011 Oct;44(4):597–607.

- Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, et al. Diagnostic properties of nerve conduction tests in population-based carpal tunnel syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003 May 7;4:9.

- Lee D, van Holsbeeck MT, Janevski PK, et al. Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Ultrasound versus electromyography. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999 Jul;37(4):859–872.

- Duncan I, Sullivan P, Lomas F. Sonography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Roentgenol. 1999 Sep;173(3):681–684.

- Hobson-Webb LD, Massey JM, Juel VC, et al. The ultrasonographic wrist-to-forearm median nerve area ratio in carpal tunnel syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008 Jun;119(6):1353–1357.

- Buchberger W, Judmaier W, Birbamer G, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Diagnosis with high-resolution sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 1992 Oct;159(4):793–798.

- Cartwright MS, Hobson-Webb LD, Boon AJ, et al. Evidence-based guideline: Neuromuscular ultrasound for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2012 Aug;46(2):287–293.

- Kanikannan MA, Boddu DB, Umamahesh, et al. Comparison of high-resolution sonography and electrophysiology in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015 Apr–Jun;18(2): 219–225.

- Kim MK, Jeon HJ, Park SH, et al. Value of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: Correlation with electrophysiological abnormalities and clinical severity. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014 Feb;55(2):78–82.

- Fowler JR, Munsch M, Tosti R, et al. Comparison of ultrasound and electrodiagnostic testing for diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: Study using a validated clinical tool as the reference standard. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Sep 3;96(17).

- Kang S, Kwon HK, Kim KH, et al. Ultrasonography of median nerve and electrophysiologic severity in carpal tunnel syndrome. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012 Feb;36(1):72–79.

- Witt JC, Hentz JG, Stevens JC. Carpal tunnel syndrome with normal nerve conduction studies. Muscle Nerve. 2004 Apr;29(4):515–522.

- Koyuncuoglu HR, Kutluhan S, Yesildag A, et al. The value of ultrasonographic measurement in carpal tunnel syndrome in patients with negative electrodiagnostic tests. Eur J Radiol. 2005 Dec;56(3):365–369.

- Fowler JR, Gaughan JP, Ilyas AM. The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: A meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011 Apr;469(4):1089–1094.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Management of carpal tunnel syndrome evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Feb 29, 2016.

- Greenberg MH, Fant JW Jr. Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided compared to blind steroid injections in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Oct 17;69:1060–1065.

- Evers S, Bryan AJ, Sanders TL, et al. Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided compared to blind steroid injections in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Jul;69(7):1060–1065.

- Jones NF, Ahn HC, Eo S. Revision surgery for persistent and recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome and for failed carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Mar;129(3):683–692.