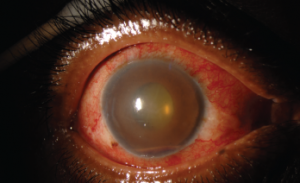

Figure 2. This external photograph of the right eye shows keratic precipitates on the corneal endothelium, corneal edema and hemorrhagic hypopyon in the setting of acute herpetic anterior uveitis.

Uveitis is an umbrella term for intraocular inflammatory diseases that can lead to vision loss. It’s not just a concern for ophthalmologists. Uveitis occurs in approximately 2–5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 6–9% of patients with psoriatic arthritis and 25% of patients with reactive arthritis. The prevalence may be as high as 33% in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.1 Thus, it’s important rheumatologists have an understanding of this potentially debilitating condition.

The Basics

Sandwiched between the dense connective tissue of the sclera externally and the neurosensory retina internally, the uvea comprises the pigmented, middle layer of the eye. Composed of the iris, ciliary body and choroid, inflammation within these structures is collectively called uveitis.

The heterogeneous causes of uveitis include trauma, autoimmune disorders, infections, drug reactions and malignancies. When a cause is not identified, which occurs in approximately half of cases, the term idiopathic is used.

Intraocular inflammation is uncommon, with an estimated incidence of 26–52 cases per 100,000 people per year due to ocular immune privilege—the phenomenon in which the eye attempts to limit local immune and inflammatory responses to preserve vision.2,3 The eye lacks lymphatic drainage, and the aqueous humor contains immunosuppressive factors, including TGF-β.4 Additionally, intraocular tissues express Fas ligand, which promotes leukocyte apoptosis.4

Classifications

Intraocular inflammation is classified on the basis of anatomic location using the standardization of uveitis nomenclature (SUN):5

- Anterior uveitis accounts for 50–90% of cases of ocular inflammation.6 It refers to inflammation of the iris or ciliary body with the focus of inflammation centered in the anterior chamber. Previous terms for anterior uveitis include iritis, iridocyclitis or anterior cyclitis.

- Intermediate uveitis and posterior uveitis occurs in the posterior chamber. Intermediate uveitis describes inflammation within the vitreous body, which includes pars planitis or posterior cyclitis.

- Posterior uveitis refers to inflammation predominately in the retina or choroid, and encompasses entities such as retinal vasculitis or neuroretinitis.

- Finally, panuveitis occurs when inflammation is evenly distributed throughout the eye and not restricted to one chamber.

Uveitis can also be classified by onset or course.6 Although the onset of uveitis can be either sudden or insidious, the course denotes the duration.

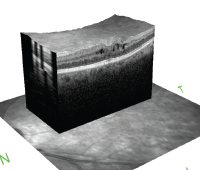

Cystoid macular edema is seen on optical coherence tomography. The hyporeflective spaces within the retina represent fluid accumulation due to inflammatory vascular leakage. This is most common cause of vision loss in patients with uveitis.

Acute uveitis describes inflammation occurring for less than six weeks with sudden onset. If inflammation resolves, treatment is stopped, but if it occurs again after three months, the uveitis is considered recurrent. If there is less than three months of inactivity and lack of a treatment-free interval between episodes of inflammation, the uveitis is considered chronic.

Uncontrolled, chronic inflammation causes structural complications leading to blindness, including macular edema, cataracts, glaucoma or neovascularization of the retina.7

As the cause of 10–15% of blindness in the U.S. and Europe, uveitis and associated complications predominately affect patients during their working years. This leads to significantly more lost wages, increased medical costs and increased rates of disability compared to age-matched peers.8-10 Thus, rapid and continued control of intraocular inflammation is required.

Diagnosis & Treatment

Prior to initiation of treatment, a serologic work-up is needed to identify an etiology and rule out infectious causes of the ocular inflammation. The tests ordered vary by clinical exam findings, provider and region, but uveitis specialists universally agree both a non-treponemal (RPR, VDRL) and a treponemal test (FTA-Abs, T. pallidum IgG, MHA-TP) are required to rule out syphilis.

Most immunosuppressive agents are used off label, given there is only one FDA-approved medication for non-infectious intermediate & posterior uveitis, & panuveitis—adalimumab.

Additional testing based on clinical picture can include a computed tomography scan of the chest without contrast if there is a high suspicion for sarcoidosis or Lyme titers in patients with a history of travel to areas where Lyme disease

is endemic.

In patients with anterior uveitis or intermediate uveitis, a positive HLA-B27 test can give prognostic information, because the inflammation is more likely to be chronic or recurrent. Most acute episodes of anterior uveitis last six weeks and, on average, recur once a year.11

Treatment is based on the anatomic location of the inflammation and the chronicity.

Acute anterior uveitis is treated with corticosteroid drops, including prednisolone acetate 1% or difluprednate 0.05%, starting at four times per day or fewer with minimal inflammation or hourly dosing when fibrin and hypopyon are present in the anterior chamber. Cycloplegic drops—such as cyclopentolate 1%, which can be used up to three times per day, or daily atropine 1%—are added to break posterior synechiae, which are abnormal adhesions between the iris and lens.

If chronic anterior uveitis cannot be controlled with three or fewer drops a day of prednisolone acetate 1% or if complications develop, systemic treatment with corticosteroids is warranted.12 Concurrently, a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agent is started to minimize the long-term side effects associated with steroid monotherapy.13

This approach is also used to treat panuveitis, posterior uveitis and intermediate uveitis with secondary complications, including retinal neovascularization, macular edema or vision loss due to vitreous haze.

Most immunosuppressive agents are used off label, given there is only one medication approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) for non-infectious intermediate and posterior uveitis, and panuveitis—adalimumab.

The American Uveitis Society has published recommendations on the use of anti-metabolite and biologic agents for ocular inflammatory disorders.14 However, treatment needs to be individualized based on patient comorbidities, age, pregnancy status and the side effect profile of each drug.

The second treatment approach is local therapy, using periocular or intraocular steroid injections. The FDA has approved several intraocular implants for the treatment of non-infectious intermediate and posterior uveitis, and panuveitis.

Options for short-term inflammation control include the 0.7 mg dexamethasone intravitreal implant (Ozurdex; Allergan) and the 0.18 mg fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant (Yutiq; EyePoint).

Long-term control can be achieved using the 0.59 mg fluocinolone acetonide anchored implant (Retisert; Bausch and Lomb) in lieu of immunosuppression.

An additional periocular treatment for macular edema is the injection of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog-40) into the sub-tenon space or into the vitreous cavity (Triesence; Alcon).

Local therapy spares the systemic side effects of immunosuppressive agents and oral corticosteroids, but it has been associated with the development of elevated intraocular pressure and cataracts. The Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) trial showed that seven years after implantation of the 0.59 mg fluocinolone acetonide-anchored implant, 45% of patients underwent glaucoma filtering surgery, and 90% received cataract surgery.15

Referral Recommended

Based on the myriad treatment options and the possible complications of unrecognized ocular inflammation, referral to a uveitis specialist is warranted to screen for ocular manifestations of autoimmune disorders. A prompt referral should be placed for evaluation of a patient with a painful, red eye. If an infection is suspected, same-day referral is necessary.

Bridging the gap between systemic disease and the eye, the uveitis specialist is a fellowship-trained ally in the treatment of patients with autoimmune disease.

Meghan Berkenstock, MD, is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, and practices at the Ocular Immunology Division of the Wilmer Eye Institute. Her research focuses on quality improvement in the treatment of patients with uveitis, and identifying and treating ocular side effects of oncologic immunotherapy medications.

Meghan Berkenstock, MD, is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, and practices at the Ocular Immunology Division of the Wilmer Eye Institute. Her research focuses on quality improvement in the treatment of patients with uveitis, and identifying and treating ocular side effects of oncologic immunotherapy medications.

ACR Guideline

In 2019, the ACR released a new guideline for the management of JIA-associated uveitis. Review the recommendations in our article, or read the full guideline.

References

- Sharma SM, Jackson D. Uveitis and spondyloarthropathies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Dec;31(6):846–862.

- Gritz DC, Wong IG. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California: The Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology. 2004 Mar;111(3):491–500.

- Suhler EB, Lloyd MJ, Choi D, et al. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers of the Pacific Northwest. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(6):890–896.e8.

- Taylor A. Ocular immune privilege. Eye (Lond). 2009 Oct;23(10):1885–1889.

- Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Sep;140(3):509–516.

- Thorne JE, Suhler E, Skup M, et al. Prevalence of noninfectious uveitis in the United States: A claims-based analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 Nov 1;134(11):1237–1245.

- Tomkins‐Netzer O, Talat L, Bar A, et al. Long‐term clinical outcome and causes of vision loss in patients with uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2014 Dec;121(12): 2387–2392.

- Miserocchi E, Fogliato G, Modorati G, Bandello F. Review on the worldwide epidemiology of uveitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013 Sep–Oct;23(5):705–717.

- Thorne JE, Skup M, Tundia N, et al. Direct and indirect resource use, healthcare costs and work force absence in patients with non-infectious intermediate, posterior or panuveitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016 Aug;94(5):e331–e339.

- Acharya NR, Tham VM, Esterberg E, et al. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis: Results from the Pacific Ocular Inflammation Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Nov;131(11):1405–1412.

- Thorne JE, Woreta FA, Dunn JP, Jabs DA. Risk of cataract development among children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-related uveitis treated with topical corticosteroids. Ophthalmology. 2010 Jul;117(7):1436–1441.

- Birnbaum AD, Jiang Y, Vasaiwala R, et al. Bilateral simultaneous-onset nongranulomatous acute anterior uveitis: Clinical presentation and etiology. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012 Nov;130(11):1389–1394.

- Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS, et al. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: Recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000 Oct;130(4):492–513.

- Levy-Clarke G, Jabs DA, Read RW, et al. Expert panel recommendations for the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor biologic agents in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders. Ophthalmology. 2014 Mar;121(3):785–796.e3.

- Writing Committee for the Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial and Follow-up Study Research Group, Kempen JH, Altaweel MM, Holbrook JT, et al. Association between long-lasting intravitreous fluocinolone acetonide implant vs systemic anti-inflammatory therapy and visual acuity at 7 years among patients with intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis. JAMA. 2017 May 16;317(19):1993–2005.