In 2021, the ACR—in concert with the Vasculitis Foundation (VF)—released four new vasculitis guidelines, one each on: 1) anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis, 2) giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu arteritis, 3) polyarteritis nodosa and 4) Kawasaki disease.1-3,11 The guideline development process is complex. For the vasculitis guidelines, this process kicked off in June 2017, when the core leadership team formed by the ACR first met in person. The ACR also convened expert and voting panels. Together, the core team and the two panels determined the project’s scope. Members of the literature review team assembled evidence using the most recent nomenclature system for vasculitis, the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature.4 A panel of patients contributed as well. In this series, we discuss the updated recommendations with authors who contributed to each guideline. Read other installments in this series.

In 2021, the ACR—in concert with the Vasculitis Foundation (VF)—released four new vasculitis guidelines, one each on: 1) anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis, 2) giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu arteritis, 3) polyarteritis nodosa and 4) Kawasaki disease.1-3,11 The guideline development process is complex. For the vasculitis guidelines, this process kicked off in June 2017, when the core leadership team formed by the ACR first met in person. The ACR also convened expert and voting panels. Together, the core team and the two panels determined the project’s scope. Members of the literature review team assembled evidence using the most recent nomenclature system for vasculitis, the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature.4 A panel of patients contributed as well. In this series, we discuss the updated recommendations with authors who contributed to each guideline. Read other installments in this series.

In this third article in the series, we talk with Philip Seo, MD, MHS, about eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). Dr. Seo, who serves as physician editor of The Rheumatologist, is the director of the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center, director of the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Fellowship Training Program, and an associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

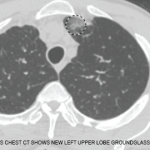

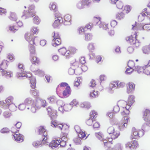

About 40% of people with EGPA are ANCA positive, but the condition is different enough from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) to need its own set of recommendations. This type of vasculitis is characterized by eosinophilia, rhinosinusitis and adult-onset asthma, all of which are difficult to treat. Moreover, a high proportion of patients develop organ-threatening disease, including aggressive neuropathy and cardiac involvement. Cardiac involvement accounts for up to half the deaths attributable to EGPA and is something we’re all concerned about.

Q: Can you talk about why the guideline authors decided to use ‘severe’ or ‘non-severe’ as a risk stratification framework for treatment, as opposed to using the Five-Factor Score (i.e., older than 65 years, cardiac insufficiency, renal insufficiency, gastrointestinal involvement, absence of otolaryngologic manifestations) when deciding on the recommendations?

Dr. Seo: The Five-Factor Score was never intended to help us decide how to treat a patient. It’s a prognostic index that says, ‘If a patient meets certain criteria, then you can predict the mortality rate at five years is this … .’ I think it’s useful when it comes to talking to a patient about what they can expect over the next several years, but it was never meant to be a treatment guide.

The terminology for ‘severe’ vs. ‘non-severe’ used to be ‘severe’ vs. ‘limited’ disease. That terminology was developed by John Stone and Ulrich Specks for the WGET trial.5 The lasting influence of that trial is the classification system Americans have used to divide patients into those who need cyclophosphamide or rituximab, for example, and those who can be treated with milder drugs, such as methotrexate. We use severe and non-severe as shorthand to represent the thinking that goes into deciding how to treat a patient.

From the guideline—Recommendation: For patients with active, severe EGPA, we conditionally recommend treatment with cyclophosphamide or rituximab over mepolizumab for remission induction.

Q: A hot topic is the role of rituximab in the treatment of EGPA. Can you talk about what led the guideline committee to make cyclophosphamide or rituximab for remission induction a conditional recommendation for EGPA? Where do you stand on it yourself?

Dr. Seo: EGPA is like the lupus of the vasculitis world. In lupus, you could have one patient who has disease that is limited to the skin and another patient with central nervous system disease and one who is losing kidney function, and they’re all classified as having systemic lupus erythematosus. In the same way, EGPA encompasses a large spectrum of patients who can look very different clinically. I think the recommendation is really speaking to the patients who look more like they have microscopic polyangiitis.

Patients with EGPA who are ANCA positive look more like patients with MPA; they tend to have glomerulonephritis, pulmonary hemorrhage and mononeuritis multiplex. ANCA-negative patients look much more like they have an eosinophilic disorder. I think rheumatologists are much more likely to see patients with refractory vasculitic manifestations of EGPA, and for those patients, I think rituximab is reasonable.

Q: The guideline recommends treatment with conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)—methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil—over rituximab or mepolizumab for patients with active, non-severe EGPA and for patients with severe EGPA whose disease has entered remission. Given its primacy in ANCA vasculitis, in which we favor rituximab for maintenance therapy, why not continue rituximab for maintenance in EGPA?

Dr. Seo: There’s an ongoing trial by the French Vasculitis Study Group examining rituximab for remission maintenance in EGPA, so maybe in two or three years I’ll have a real answer for you.6 In the meantime, that trial will be the only solid data we’re going to have. If you’ve got an EGPA patient who basically has glomerulonephritis, I think what you said is really reasonable. Of course, then we would consider rituximab for remission maintenance. But there aren’t a lot of data supporting that approach.

As for mepolizumab, remember that the MIRRA study, which was run by Michael E. Wechsler, MD, only looked at patients with mild to moderate disease, not patients with life-threatening manifestations of EGPA.7 It doesn’t mean mepolizumab couldn’t help those patients, but I think it’s still an open question for that patient population.

Q: Do you see a role for mepolizumab as an adjunct therapy, or would you lean toward conventional synthetic DMARDs for someone who has the vasculitic variety of EGPA?

Dr. Seo: I think mepolizumab is an amazing drug for patients with chronic sinusitis or chronic asthma who require rescue inhalers on a regular basis and they’re constantly getting Medrol Dosepaks (methylprednisolone) to keep their asthma under control. What I’m not sure about is if it’s also a great drug for a patient with glomerulonephritis or pulmonary hemorrhage or mononeuritis multiplex. For a lot of patients I’ll end up using both: I’ll use a traditional DMARD to prevent the relapse of the vasculitic component, and I’ll use mepolizumab or another anti-interleukin (IL) 5 agent to keep the respiratory symptoms under control.

The great thing about mepolizumab, in particular, is that it not only works for EGPA, but it works for chronic eosinophilic pneumonia and for the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. As long as you know you’re in that ballpark, and your patient doesn’t have a parasite—like strongyloides for example—mepolizumab probably isn’t a bad agent. It’s probably safer for most patients to block IL-5 than it is to give them prednisone.

Q: The guidelines did conditionally recommend that patients with non-severe disease be started on either mepolizumab or conventional synthetic DMARDs over glucocorticoids alone. Doesn’t this establish a principle whereby all patients who are newly diagnosed with EGPA, non-severe and severe, will get a DMARD?

Dr. Seo: I think it acknowledges that a lot of the people putting together these guidelines run vasculitis centers of our own. And because of that, we tend to see people who have already seen maybe two or three other rheumatologists, and they’re just not doing well. I think the bias is toward being a bit more aggressive when it comes to using additional agents besides glucocorticoids. On the other hand, a decent number of patients with EGPA basically just have bad asthma, and I think for those patients, it would be reasonable to think of glucocorticoid monotherapy. That probably doesn’t encompass all the patients you might see, though.

Q: When do you pull back the glucocorticoids?

Dr. Seo: There’s a story at Hopkins about Mary Betty Stevens, MD. She was responsible for training a lot of people who are now division directors or department directors. The first piece of advice she would give to a fellow would be, ‘Don’t mess with the prednisone.’ That’s because a lot of patients would be on 3 or 4 mg, and inevitably the first-year fellow would taper the prednisone the patient didn’t seem to need, and inevitably the patient would have an awful relapse and require hospitalization.

For patients who don’t have life-threatening manifestations of EGPA, I generally start with 0.5 mg/kg of prednisone. An old study from Wolfgang Gross’ group showed that most patients end up taking 7.5 mg of prednisolone daily to keep their disease under control.8 I think it’s true for a lot of patients with EGPA—no matter what you treat them with, they still need a little bit of prednisone, especially to keep their bronchospasm under control. Once I get to 10 mg of prednisone, I start to slow down the prednisone taper. I’ll taper by 1 mg increments once a month, and I wait until their symptoms, typically bronchospasm or sinusitis, return.

If someone manages to taper completely off steroids, I’m just pleasantly surprised. For the majority of patients, though, they may not complain of frank bronchospasm but they did notice they had to cut back on their activities and they’re not exactly sure why. That’s my clue the prednisone taper has probably gone as far as it can.

From the guideline—Recommendation: For patients with EGPA, we conditionally recommend obtaining an echocardiogram at the time of diagnosis.

Q: Going from treatment to screening, do you think we’re missing asymptomatic cardiac disease in GPA? As I mentioned, half of the deaths attributable to EGPA come from cardiac disease.

Dr. Seo: Ulrich Specks, MD, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.—a giant in the field—did a case series years ago evaluating patients with GPA. He demonstrated that their ejection fraction decreased at the time of flare and then became normal again when the flare was treated. That observation doesn’t really influence treatment, but it does make me think there’s probably a higher proportion of patients with cardiac disease out there who we’ll never know about because we don’t standardly perform echocardiograms.

Q: What led the guideline committee to recommend a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE)? They could have recommended a simple electrocardiogram (ECG), which is quicker, cheaper, and more accessible in general, or they could have gone straight to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which provides more information about inflammatory lesions.

Dr. Seo: I think we were trying to split the difference between cost effectiveness and efficacy. Take the ECG, for example. I’ll go back to the Framingham data. Framingham indicates that ECGs are effective at diagnosing left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in maybe the 7% of patients.9,10 Even if you would say that your cardiologist is 10 times better than the Framingham cardiologists, they’re only getting that finding in 30% of patients. I feel like the ECG probably isn’t a great screening tool to find all the cardiac dysfunction that we’re looking for in our patients.

At the other end of the spectrum are EGPA patients with patchy eosinophilic infiltrates in their hearts that don’t seem to influence therapy; they just seem to go away when you put the person on whatever therapy you were going to give them anyway. I feel like we would get a lot of information from cardiac MRIs that wouldn’t necessarily be useful because we wouldn’t know what to do with it.

Q: So getting a more sensitive screening modality doesn’t necessarily improve actual care. Is there anything else you wanted to make sure people know about the EGPA guidelines?

Dr. Seo: When I give a talk, the last 15 minutes are often reserved for questions. I call that time “Stump the Chump” because audience members almost always use that time to present patients who break all the rules. I think that happens especially frequently with EGPA, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the readers out there have patients in their own practices who break all the rules and for whom these guideline recommendations won’t work. I would just say the EGPA guidelines really are just that—guidelines to get you started.

Michael Putman, MD (@EBRheum), is an assistant professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Wauwatosa, where he is the associate fellowship program director and the medical director of the vasculitis program.

Michael Putman, MD (@EBRheum), is an assistant professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Wauwatosa, where he is the associate fellowship program director and the medical director of the vasculitis program.

References

- Chung SA, Langford CA, Maz M, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody–Associated Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol and Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Jul 8. Online ahead of print.

- Maz M, Chung SA, Abril A, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Giant Cell Arteritis and Takayasu Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol and Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Jul 8. Online ahead of print.

- Chung SA, Gorelik M, Langford CA, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Polyarteritis Nodosa. Arthritis Rheumatol and Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Jul 8. Online ahead of print.

- Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013 Oct;17(5):603–606.

- The Wegener’s Granulomatosis Etanercept Trial (WGET) Research Group. Etanercept plus standard therapy for Wegener’s granulomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jan 27;352:351–361.

- French Vasculitis Study Group. Rituximab in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (REOVAS). NCT02807103. ClinicalTrials.gov.

- Wechsler ME, Akuthota P, Jayne D, et al. Mepolizumab or placebo for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. N Engl J Med. 2017 May 18;376(20):1921–1932.

- Moosig F, Bremer JP, Hellmich B, et al. A vasculitis centre based management strategy leads to improved outcome in eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss, EGPA): Monocentric experiences in 150 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jun;72(6):1011–1017.

- Oliveira GHM, Seward JB, Tsang TSM, Specks U. Echocardiographic findings in patients with Wegener granulomatosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005 Nov;80(11):1435–1440.

- Sklyar E, Ginelli P, Barton A, et al. Validity of electrocardiographic criteria for increased left ventricular mass in young patients in the general population. World J Cardiol. 2017 Mar 26; 9(3):248–254.

- Gorelik M, Chung SA, Ardalan K, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Kawasaki Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022 Apr; 74(4):586–596; and Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022 Apr;74(4):538–548.