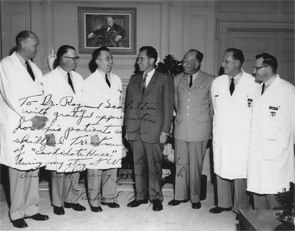

Dr. Scalettar and members of the Walter Reed treatment team with Richard Nixon.

Dr. Scalettar stayed at Walter Reed until 1962, when he joined a private practice that grew to nine internists, each with a different subspecialty. During his 54-year medical career at Washington Internal Medical Group in Washington, D.C., he practiced as an internist and rheumatologist.

“These were ground-breaking years for rheumatology,” says Dr. Scalettar, who witnessed major treatment changes and the emergence of new pharmaceuticals. “Gold injections had been the standard treatment for rheumatoid arthritis until the 1980s. We no longer use this medication.”

In 1948, anti-inflammatory drugs, in the form of corticosteroids, began making their debut. However, the cost of cortisone derivatives, such as prednisone, was too high for many patients. So rheumatologists prescribed huge doses of aspirin—the backbone of anti-inflammatory drugs—which produced such side effects as gastritis and ringing in the ears.

Due to a host of production problems, he says it took almost 10 years for the cost of corticosteroids to drop. By then, indomethacin was on the market. So was hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug that also helped patients battle lupus. The next major drug appeared in the 1980s, methotrexate, which is still used today to treat psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Researchers at the NIH were also making progress with effective treatments for gout and gouty arthritis. During the 1960s, he remembers the introduction of medication that lowered uric acid by excretion through the kidneys.

‘Gold injections had been the standard treatment for rheumatoid arthritis until the 1980s.’ —Dr. Scalettar

More Work to Be Done

Throughout his career, Dr. Scalettar also took a special interest in the politics of medicine and, ultimately, served as board chair for the American Medical Association. In this role, he appeared on numerous TV and radio programs and testified before Congress during the 1980s.

“I always began my interview by saying, ‘I am a rheumatologist,’ and explained what rheumatology was,” he says. “That helped put rheumatology on the map.”

As rheumatology research expands to new frontiers, he envisions future medications being tailored to each person, based on an individual’s unique genetic make-up.

As for his future, retirement isn’t his style. He now works as a consultant for local senior living communities and continues to address the inequalities of the healthcare system.

“Years ago, I had no idea that I wanted to be a rheumatologist,” says Dr. Scalettar, adding that he’s grateful to the Army commander who helped launch his career. “I’ve been very fortunate to have such a career where I could be of service to so many people.”