“Yes sir.”

That was the response of Raymond Scalettar, MD, DSc, FACP, when his commanding officer told him the U.S. Army wanted him to switch specialties—from gastroenterology to rheumatology.

There was only one problem.

Dr. Scalettar

Dr. Scalettar wasn’t exactly sure what that would entail. That was the mid-1950s. Back then, rheumatology was barely out of the womb. Residency and fellowship programs for the fledgling specialty were scarce. Rigorous scientific studies on rheumatology were uncommon. Even treatments were based on impressions.

Dr. Scalettar remembers that scenario well, especially because it was the impetus for launching his 60-year medical career as a rheumatologist. Since then, he has been recognized as a Master of the American College of Rheumatology, worked in private practice for over half a century and served as a clinical professor of medicine at George Washington University Medical Center. Now 87 years old and recently retired, Dr. Scalettar is one of the field’s pioneers, a living historian who can travel back to rheumatology’s roots and reveal the story of its evolution.

Major Advancements

After graduating from SUNY (State University of New York) Downstate Medical Center in 1954, Dr. Scalettar joined the U.S. Air Force as a first lieutenant intern scheduled to become a flight surgeon. But while completing his internship at Walter Reed General Hospital in Washington, D.C. (a U.S. Army facility now called Walter Reed National Military Medical Center), he accepted an Army commander’s invitation to resign his Air Force commission and join the Army to pursue his internal medicine residency.

Capt. Scalettar

So in 1955, he metamorphosed into Army Capt. Scalettar and was assigned to the former Army Medical Field Service School in San Antonio, Texas. The following year, he returned to Walter Reed, changed his specialty from gastroenterology to rheumatology due to the hospital’s need for a rheumatologist and completed his residency in 1958.

“We had a huge population of patients with inflammatory arthritis,” Dr. Scalettar says, explaining that Joseph Bunim, MD, who was setting up the National Institutes of Health Arthritis Center, was his mentor. “We learned from our patients and tried various treatments.”

In 1960, he became chief of rheumatology at Walter Reed, treating VIPs that included then Vice President Richard Nixon, who was running for president, diagnosing him with septic arthritis due to hemolytic staph aureus.

That experience prompted Dr. Scalettar to write an historical article for the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1984 titled, “Presidential Candidate Disability,” which focused on problems the country would face if a presidential candidate became ill. The article drew attention this fall from The Washington Post and The Guardian, a British newspaper, when Presidential Candidate Clinton was diagnosed with pneumonia. He also wrote a commentary for The Rheumatologist in 2009 on President Barack Obama’s healthcare reform and Secretary Clinton’s address to the AMA’s House of Delegates.

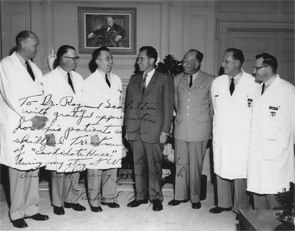

Dr. Scalettar and members of the Walter Reed treatment team with Richard Nixon.

Dr. Scalettar stayed at Walter Reed until 1962, when he joined a private practice that grew to nine internists, each with a different subspecialty. During his 54-year medical career at Washington Internal Medical Group in Washington, D.C., he practiced as an internist and rheumatologist.

“These were ground-breaking years for rheumatology,” says Dr. Scalettar, who witnessed major treatment changes and the emergence of new pharmaceuticals. “Gold injections had been the standard treatment for rheumatoid arthritis until the 1980s. We no longer use this medication.”

In 1948, anti-inflammatory drugs, in the form of corticosteroids, began making their debut. However, the cost of cortisone derivatives, such as prednisone, was too high for many patients. So rheumatologists prescribed huge doses of aspirin—the backbone of anti-inflammatory drugs—which produced such side effects as gastritis and ringing in the ears.

Due to a host of production problems, he says it took almost 10 years for the cost of corticosteroids to drop. By then, indomethacin was on the market. So was hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug that also helped patients battle lupus. The next major drug appeared in the 1980s, methotrexate, which is still used today to treat psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Researchers at the NIH were also making progress with effective treatments for gout and gouty arthritis. During the 1960s, he remembers the introduction of medication that lowered uric acid by excretion through the kidneys.

‘Gold injections had been the standard treatment for rheumatoid arthritis until the 1980s.’ —Dr. Scalettar

More Work to Be Done

Throughout his career, Dr. Scalettar also took a special interest in the politics of medicine and, ultimately, served as board chair for the American Medical Association. In this role, he appeared on numerous TV and radio programs and testified before Congress during the 1980s.

“I always began my interview by saying, ‘I am a rheumatologist,’ and explained what rheumatology was,” he says. “That helped put rheumatology on the map.”

As rheumatology research expands to new frontiers, he envisions future medications being tailored to each person, based on an individual’s unique genetic make-up.

As for his future, retirement isn’t his style. He now works as a consultant for local senior living communities and continues to address the inequalities of the healthcare system.

“Years ago, I had no idea that I wanted to be a rheumatologist,” says Dr. Scalettar, adding that he’s grateful to the Army commander who helped launch his career. “I’ve been very fortunate to have such a career where I could be of service to so many people.”

Carol Patton is a writer in Las Vegas.