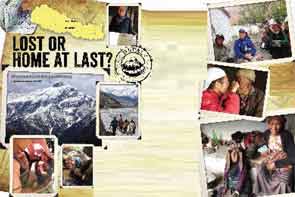

‘Come, Steve!” I heard Kunga yell from across the small, irrigate wheat paddies as I walked back into Samdzong, a village of 17 houses, 60 people, in the Upper Mustang of Nepal. Kunga Gurung, a 26-year-old monk who just passed his medical exams in Kathmandu after three years of medical school, was coming out of a mud-brick, thatch-roofed home. He took me inside where I found a very worried mother, Yuka, holding her three-day-old baby girl, Karsung, who was listless and had yet to feed. One in three babies born in the village last year didn’t survive. The wind is thought to cause most illness, and it blows constantly here on the south Tibetan plateau. Yuka was protecting Karsung with a goatskin wrap and three wool blankets. Once she was uncovered, I could see that the umbilical cord was not infected and all extremities moved. Little Karsung perked up as I held her up in the fresh air and, with Kunga’s breastfeeding instruction, Yuka got Karsung to latch on. We relaxed and started to leave when grandmother, Yandur, asked if I could see her husband, Choesang, an 83-year-old meme or grandfather, who was across the room lying under four blankets next to the unattended loom. Meme had been listless for three days, moaning, eating and drinking little, except for the three daily doses of “medicinal” raksi (a local distilled rice alcohol) from Yandur. He had a temperature of 101ºF, a rare bowel trickle, exquisite rebound abdominal tenderness, and dark urine. I prescribed ceftriaxone IM, triple H. pylori therapy, and rehydration fluids, but suspected that this treatment would be insufficient.

Initial Hesitation

When asked to accompany an archeological expedition to the Upper Mustang of Nepal, I wondered if a 62-year-old rheumatologist on antiarrhythmics, with right knee osteoarthritis, was appropriate for the job. Would rheumatology practice translate to expedition and third-world medicine? My indecision changed to commitment when my group allowed me the time go. Sir William Murray predicted what then happened: “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back … the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred.”1

The Upper Mustang is the world’s last remaining ethnically pure, Tibetan, Buddhist culture, situated in the Kali Gandaki valley of north central Nepal, the rest of which is 90% Hindu. It is one of the poorest countries in the world. My family-medicine colleague, Bruce Gardner, MD—who has made three medical trips to Nepal—oriented me to expedition care and gave me a draft supply list. Stephen Bezruchka, MD, MPH, senior lecturer in the department of global health at the University of Washington in Seattle, offered insights about global health “sustainable practices” in third-world countries, and gave me contacts. I read and supplied for high-altitude illness (descend), diarrhea (treat early), foot care (prevent), everything from migraine and motion sickness to H. pylori worms, dermatitis, and wound care. I came prepared with large supplies of medication my building pharmacy sold to me at near cost or that were donated by colleagues. I gathered two duffels of supplies to donate: basic hospital instruments, over 30 medications, basic first-aid supplies, medical books, reading glasses, and other supplies would all eventually find a home in Kunga’s Chhoedhe Monastery medical clinic.