‘Come, Steve!” I heard Kunga yell from across the small, irrigate wheat paddies as I walked back into Samdzong, a village of 17 houses, 60 people, in the Upper Mustang of Nepal. Kunga Gurung, a 26-year-old monk who just passed his medical exams in Kathmandu after three years of medical school, was coming out of a mud-brick, thatch-roofed home. He took me inside where I found a very worried mother, Yuka, holding her three-day-old baby girl, Karsung, who was listless and had yet to feed. One in three babies born in the village last year didn’t survive. The wind is thought to cause most illness, and it blows constantly here on the south Tibetan plateau. Yuka was protecting Karsung with a goatskin wrap and three wool blankets. Once she was uncovered, I could see that the umbilical cord was not infected and all extremities moved. Little Karsung perked up as I held her up in the fresh air and, with Kunga’s breastfeeding instruction, Yuka got Karsung to latch on. We relaxed and started to leave when grandmother, Yandur, asked if I could see her husband, Choesang, an 83-year-old meme or grandfather, who was across the room lying under four blankets next to the unattended loom. Meme had been listless for three days, moaning, eating and drinking little, except for the three daily doses of “medicinal” raksi (a local distilled rice alcohol) from Yandur. He had a temperature of 101ºF, a rare bowel trickle, exquisite rebound abdominal tenderness, and dark urine. I prescribed ceftriaxone IM, triple H. pylori therapy, and rehydration fluids, but suspected that this treatment would be insufficient.

Initial Hesitation

When asked to accompany an archeological expedition to the Upper Mustang of Nepal, I wondered if a 62-year-old rheumatologist on antiarrhythmics, with right knee osteoarthritis, was appropriate for the job. Would rheumatology practice translate to expedition and third-world medicine? My indecision changed to commitment when my group allowed me the time go. Sir William Murray predicted what then happened: “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back … the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred.”1

The Upper Mustang is the world’s last remaining ethnically pure, Tibetan, Buddhist culture, situated in the Kali Gandaki valley of north central Nepal, the rest of which is 90% Hindu. It is one of the poorest countries in the world. My family-medicine colleague, Bruce Gardner, MD—who has made three medical trips to Nepal—oriented me to expedition care and gave me a draft supply list. Stephen Bezruchka, MD, MPH, senior lecturer in the department of global health at the University of Washington in Seattle, offered insights about global health “sustainable practices” in third-world countries, and gave me contacts. I read and supplied for high-altitude illness (descend), diarrhea (treat early), foot care (prevent), everything from migraine and motion sickness to H. pylori worms, dermatitis, and wound care. I came prepared with large supplies of medication my building pharmacy sold to me at near cost or that were donated by colleagues. I gathered two duffels of supplies to donate: basic hospital instruments, over 30 medications, basic first-aid supplies, medical books, reading glasses, and other supplies would all eventually find a home in Kunga’s Chhoedhe Monastery medical clinic.

Our Dedicated Team

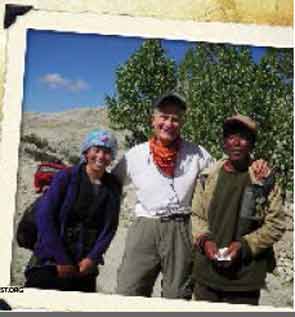

“Providence moved” via the web and the wonderful people on the expedition. I found the CIWEC Travel Clinic website (http://ciwec-clinic.com), director Dr. Prativa Poudy, and head nurse Francoise Pahul, all very helpful. After arrival in Kathmandu, anthropologist Caroll Dunham then invited me to lunch with her photographer husband, Thomas Kelly. They introduced me to Kunga. I learned that Kunga’s monestary was in LoManthang in the Upper Mustang, where we were headed. Expedition leaders Pete Athans, the first non-Sherpa to summit Mt. Everest seven times, and his wife Liesl Clark, photographer and producer of the National Geographic documentary, The Cave People of the Himalaya, with children, Cleo (7) and Finn (10), promptly invited Kunga to join us as my interpreter and medical colleague. Archeologist Mark Aldenderfer, PhD, bioarcheologist Jackie Eng, PhD, Indian post-doc Kavita Bist, PhD, and climber Ang Sherpa made up the rest of full-time professional team, and each became a teacher and companion.

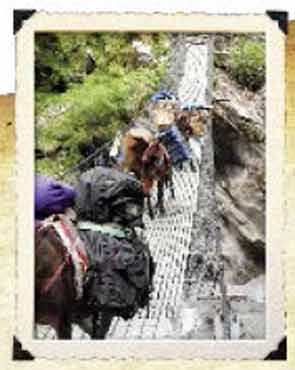

We trekked, horse-packed, and rode Jeeps up though the ancient kingdom of Lo, founded in 1380, with a 25-generation monarchy that only ended in 2008. The Kali Gandaki river descends through walled canyons, lined with hundreds of living and mortuary cave systems dating from 1000 BCE to 1500 CE, before diving through the deepest ravine in the world. Pete and Liesl have led a decade of expeditions, discovering caves with 15th century Buddhist wall paintings, Tibetan scripts in ink, silver, and gold, and bone remains suggesting evidence of different mortuary practices, including defleshing and sky burials, as well as supporting libraries in several villages and working closely with the Nepal Department of Archeology to assure proper reporting of all findings and securing them for the local villages.

For the expedition group, I cared for 29 minor problems, but I was prepared for cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Eight-hour Jeep rides meant that back-care education was important. Liesl, who is a recycling and environmental health teacher/blogger, loved my use of a one-liter, air-filled water bottle for lumbar support. I taped a sprained ankle, removed splinters, dressed blisters, treated a paronychia, and injected a first metatarsophalangeal bursitis. Metoclopramide and ondansetron made hours of mountain bus and Jeep rides tolerable for the woozy, and low-dose valium dampened the anticipatory anxiety. I treated two episodes of traveler’s diarrhea with single-day therapy at the earliest symptoms, followed with peptobismuth, preventing full impact of the condition.

The most unexpected concern occurred two days into the trip when the kids were exposed to chickenpox. Without the children having a clear history of past exposure, and because we were heading into the remote Himalayas, I taxied to an open-air pharmacy recommended by the CIWEC clinic, bought two doses of vaccination, and administered them in the hotel room. Mild to severe local reactions occurred (one child had probably had chickenpox before), and one night of fever required a late-evening hotel-room visit and acetaminophen. The next morning, I finally relaxed on seeing them both spryly eating breakfast.

Sustainability Through Kunga

Each evening in a new tea-house room, Kunga and I saw villagers, who lined up outside after word got out. During the month, I saw 53 villagers, and the most common complaint was back pain. Forehead yokes keep the heavy loads fairly well aligned to protect lumbar discs, but straight-legged, flexed posture while working the fields is perfect for disc compression and herniation. I drew pictures and demonstrated lordotic posture and taught Williams extension exercises. In Samdzong, under the midday sun, I held the first back-pain prevention class, to the amusement of many. Kunga wrote excellent histories in my log and did rudimentary exams, and I taught him lung, abdominal, back, and joint examination. For osteoarthritis of the knee, I gave two intraarticular steroid shots and distributed small bags of low-dose ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and topical creams. Several men with chronic gastritis were treated for H. pylori, and another with hematochezia was treated for amebic colitis. One man with possible reactivation tuberculosis was sent to Pohkara. I asked him to wear a mask all day, which he did, and I am happy to report that I did not convert my purified protein derivative skin test.

Teaching Kunga allowed me to leave something sustainable behind. Differential diagnosis and targeted treatment is different from the traditional medicine instruction he received growing up (which was Sowa-Rigpa, similar to Ayurveda). In Tibetan medicine, illness is due to imbalance in the five basic elements, and medicinal herbs, diet, activity, and mantras are used to rebalance and treat most illness.2 When I asked, a young amchi (a traditional Tibetan medicine practitioner), Lhundup Bista, opined that at least 40% of illness was due to imbalance in the emotional/spiritual domains. His father, Amchi Gysato Bista, said it was difficult to treat osteoarthritis of the knee, but that his diet therapies did well in treating polyarthritis in younger patients, similar to the results of Ayurvedic medicine in treating rheumatoid arthritis.3

Ancestral bones from the caves showed evidence of vertebral compression fractures, erosive shoulder arthritis, and Achilles calcifications. The presence of mechanical back pain, inflammatory arthritis and enthesitis, osteoporosis, and emotional distress suggests rheumatology illness in the Upper Mustang may not be that different from that in Seattle.

Kunga is planning on getting a Master’s in public health, and is committed to the healthcare of the Mustang. While there is one doctor for every 850 people in the Kathmandu valley, rural areas have one doctor for every 150,000 people, and infant mortality more than doubles to 13.2%.4 I left Kunga medical books, instruments and supplies, and exam notes. We have e-mailed since my return, and I just know he will make a difference!

Returning Renewed

I visited meme Choesang for the last time four days after I found him with a ridge belly. My suspicions had been wrong—he didn’t die and, in fact, was awake and eating. Ceftriaxone IM, triple H. pylori therapy, and rehydration fluids may have helped, or maybe it was his karma. Either way, he won this battle to not to leave this world, and suckling Karsung was winning her battle to stay.

So, where have you always wanted to go? Do it. You will learn expedition medicine and third-world medicine easily, given your internal medicine foundation. As a rheumatologist, you deconstruct complex illness through patient stories, do comprehensive multisystem examinations, and think about the whole person. These skills will allow you to practice medicine anywhere, but it is your comfort dealing with the unknown, your ability to offer hope when all the answers aren’t known, and to hold your patient’s hand during any crisis that will assure your usefulness. Anywhere you go, there will be people in pain, with inflammation and disability, who will appreciate what you have to offer. Being so close to the challenges and joys of simple living will fill your heart and renew your soul.

Dr. Overman is a founding member of The Seattle Arthritis Clinic and chief of rheumatology at Northwest/University of Washington Medical Center. He has practiced rheumatology in Seattle for 30 years and co-authored You Don’t LOOK Sick! Living Well with Invisible Chronic Illness. He is currently clinical professor of medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

References

- Murray WH. The Scottish Himalayan Expedition. London: Dent; 1951.

- Craig SR. Healing Elements: Efficacy and the Social Ecologies of Tibetan Medicine. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2012.

- Furst DE, Venkatraman MM, Krishna Swamy BG, et al. Well controlled, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of classical Ayurvedic treatment are possible in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:392-393.

- Patan Academy of Health Sciences. Nepal at a Glance. Available at www.pahs.edu.np/about/about-nepal. Accessed August 29, 2013.