Figure 1

Post pictures of people using canes and doing fun activites in your waiting room.

Walking as good medicine is an ancient notion credited to Hippocrates.

Modern medicine continues to support walking as a means to a healthier life. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) advocates that adults participate in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity weekly. Walking is one way people can meet that goal. Previously, the HHS recommended engaging in 10-minute bursts of activity. However, the HHS now notes that even shorter periods of activity can be an effective way of meeting the 150-minute goal.1

Simple assistive devices, such as canes, can help people with impaired balance or joint pain stay active safely. However, some people may not understand how a cane can help them stay active or may resist using a cane for other reasons. After years of walking without assistive devices, regularly walking with a cane is a significant change. Patients may need our help to adopt this new behavior. We share several points to assist with patient-provider conversations to support the transition to walking with a cane.

Barriers to Cane Use

We humans are loss averse. We may emotionally or psychologically perceive a loss more intensely than we would experience a comparable gain. In other words, when we have something we value, we will work hard to not give it up, even when it may not be in our best interest. Some people may see using a cane as a loss of independence and youth, and it may be hard for them to see the gain of safety with mobility that a cane provides. Some people may give up walking rather than commit to using a cane.

Common perceptions about canes are barriers to their use. Canes are often viewed as indicators of frailty, old age and dependency. Because of these views, rather than being in public with a cane, some people may choose not to leave their homes. This decision may lead to a loss of independence as they become increasingly reliant on others to deliver their groceries and run their errands. Individuals may not recognize that a cane can promote independence, taking weight off a painful joint and assisting with balance issues while standing and walking.

Other barriers to cane use include uncertainty regarding how to select, obtain and use a cane, and low self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in one’s abilities).

Individuals also may not fully understand the potential risks of not using a cane. They may think of a fall as a minor event that they can walk off and not realize that it could result in significant injury and further loss of independence.

Accepting the Cane

Starting to use a cane can be a big life transition. The role of the healthcare provider is to help patients accept the cane by understanding their life goals and addressing barriers.

Most patients want to maintain their independence with regard to performing daily activities, and their work and social interactions. Discussions can focus on how the cane promotes independence by helping them maintain safe mobility so they can meet their goals. Canes and other mobility devices can allow them to walk more so they can run their own errands, stay physically active and engage in social activities.

Although we don’t want to frighten patients into using a cane, it is import-ant to reinforce what can be lost by not using one and alerting them to the potential consequences of falls. Some simple ways to promote cane acceptance:

- Post pictures in the waiting room of people using a cane and enjoying themselves (see Figure 1).

- Give a cane as a gift. Giving your patient a cane, free of charge and fitted to them, will likely foster a long-lasting, favorable impression of your practice. A feeling of gratitude can trigger low-cost advertising by patients through word of mouth, with snowballing effects. Add your practice logo to the gift for an additional marketing opportunity. Single-point canes are the most common style required and can be purchased for less than $12 on Amazon.3

- The person on your team who has the best alliance/relationship with your patient could give the cane to the patient.

- Use loss framing to promote buy-in. For example, “A good reason to use a cane is to prevent a loss of walking ability and independence.”

Figure 2

To fit a cane, have the patient stand with their arm resting at the side of their trunk. The level of their wrist joint is where the top of the cane should be.

Cane Fit & Use

- The height of the cane is guided by having the patient stand with their arm resting at the side of their trunk. The level of their wrist joint is where the top of the cane should be (see Figure 2).

- The cane is held in the opposite hand of the involved leg to foster a more natural gait pattern.

- If the cane is beneficial, your patient will notice right away. A cane that is too tall will be harder to pick up and move forward. A cane that is too short will cause leaning to one side.2 Both situations will compromise balance.

- To negotiate steps, the stronger leg leads going up and the involved/ weaker leg leads going down. The cane always moves with the involved leg (see Figure 3, below).

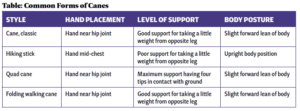

Cane Comparisons

A plethora of cane styles exists to choose from, including various handles, grip cushions and bases of support (i.e., where the cane hits the ground). Much like incorporating a patients’ choice to rheumatic treat- ment options, an individual can choose a cane that best fits their physical and optic needs. A soft han- dle grip may provide the best comfort for individuals with arthritis. Some common forms of canes are described in the table above.

Figure 3

The cane always moves with the involved leg.

Conclusion

Canes are important tools to help people stay on their feet, minimize sedentary behavior, move and lubricate joints and muscles, and foster better joint and muscle health. The third point of floor contact provided by a cane can help prevent falls, especially for older adults. Providing a cane at a healthcare appointment may optimize individuals’ use of a cane.

Yvonne Golightly, PT, MS, PhD, is a professor and assistant dean for research at the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Allied Health Professions, Omaha. She is a musculoskeletal epidemiologist and a physical therapist with 20 years of experience in research and over a decade of clinical practice.

Aileen Ledingham, PT, MA, PhD, is a physical therapist at Mount Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, Mass., where she specializes in rheumatology, particularly physical therapy for older patients with knee issues. She also serves as the 58th president of the Association of Rheumatology Professionals.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Anna Lawrence for her assistance in the development of this article.

References

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2018. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf.

- Mayo Clinic. Tips for choosing and using canes. 2023 May 26. Accessed 2024 May 23. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/healthy-aging/in-depth/canes/art-20548206.

- How to choose the right cane. Arthritis Foundation. (n.d.) https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/managing-pain/joint-protection/how-to-choose-the-right-cane.