Although ophthalmologists and rheumatologists come from the same medical-school background, our training can diverge so much that even the language we speak is incompletely shared. We know many rheumatologists who stare uncertainly at the notations that are the standard nomenclature for an eye examination. And we know ophthalmologists who are unfamiliar with the new drugs—including the biologics—that are now the mainstay of immunosuppressive therapy. Given the complexity of systemic inflammatory diseases, miscommunication about ocular problems can have serious consequences, causing delays in diagnoses and even misdirected therapy.

Case for Collaboration

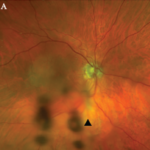

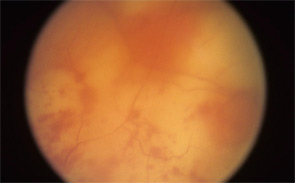

Consider, for example, the management issues raised when the the Uveitis Clinic Casey Eye Institute at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland recently evaluated a patient with Wegener’s granulomatosis for retinal vasculitis. The patient was a 55-year-old female with biopsy-proven Wegener’s that had been treated with prednisone and cyclophosphamide. When the patient began to develop visual loss in one eye, her Wegener’s was seemingly in remission. The dilated ophthalmologic examination, however, demonstrated widespread retinal vasculitis. This examination also revealed large patches of creamy retinal injury that are characteristic of acute retinal necrosis (ARN), a herpetic infection that is rare but much more common in an immunocompromised host (see Figure 1).

figure 1: Acute retinal necrosis from herpes virus infection.

The rheumatologic perspective was important in this case because we know that patients with a systemic vasculitis, such as polyarteritis or Wegener’s granulomatosis, rarely develop retinal vasculitis from the disease itself—especially if adequately treated. The ophthalmology perspective was equally important because the diagnosis of ARN is usually made by clinical examination that requires indirect ophthalmoscopy to identify the characteristic lesions. These lesions are often in the peripheral retina. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for a specific virus using surgically obtained ocular fluid can confirm the diagnosis. By amalgamating expertise in rheumatology and ophthalmology, we were able to appropriately diagnose this patient. The proper treatment of ARN is to reduce immunosuppression and initiate anti-viral therapy.

Ophthalmology Refresher

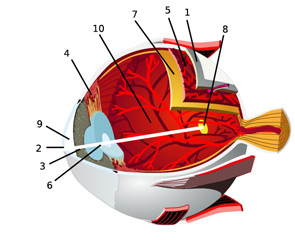

In an effort to facilitate communications with our ophthalmologic peers, this article will review the anatomy of the eye and the salient types of involvement in major rheumatologic diseases. (See Figure 2, for an overview of ocular anatomy.)

The retina is the innermost neural layer coating the back of the eye. The most important part of the retina is the macula (8), where light is focused. The anterior chamber of the eye (9) lies between the cornea and lens. This chamber contains aqueous humor, which, like cerebrospinal fluid, contains virtually no cells and minimal protein. The largest compartment in the eye is the vitreous cavity posterior to the lens (10). Like synovial fluid, vitreous humor is rich in hyalouronic acid.

Source: Chabacano. See http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Eye-diagram_no_circles_border.svg for license terms.

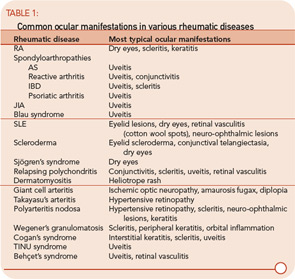

Ocular involvement is common in rheumatologic disease and varies among different diagnoses. The major ophthalmic manifestations of rheumatic diseases include uveitis, conjunctivitis, scleritis, retinal vasculitis, dry eye syndrome, orbital inflammation, and neuro-ophthalmic lesions. The patterns of common involvement are listed in Table 1 (TK). Among the listed ocular manifestations, uveitis is the most common vision-threatening inflammation associated with rheumatic diseases.1

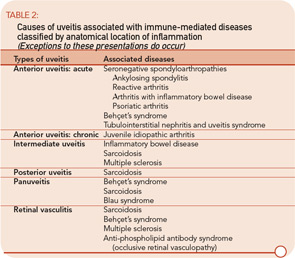

The etiologies of uveitis include infection, trauma, tumor, or immune-mediated processes. Uveitis is commonly classified by anatomical location of inflammation into anterior, intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis.2

- Anterior uveitis: When the primary site of inflammation is in the anterior chamber, a synonym for iritis or iridocyclitis.

- Intermediate uveitis: When the vitreous is the major site of inflammation.

- Pars planitis: The subset of intermediate uveitis characterized by leukocytic exudates called a snowbank or snowball at the peripheral retina or pars plana.

- Posterior uveitis: When the retina and/or choroid are the primary site of involvement. Includes including retinitis, choroiditis, chorioretinitis, and retinochoroiditis. The abnormalities can usually be observed by fundoscopic examination.

- Panuveitis: Reserved for situations in which inflammation is observed in the anterior chamber, vitreous, retina, and/or choroid.

- Retinal vasculitis: Indicates inflammation in retinal vessels and occasionally occurs without a concomitant uveitis.

Uveitis subsets can also be characterized the following features: onset (sudden versus insidious), laterality (unilateral versus bilateral), duration (limited versus chronic), continuity (recurrent versus persistent), and presence of complications such as the iris sticking to the lens (a phenomenon known as posterior synechiae). Uveitis is termed granulomatous if large concretions of leukocytes adhere to the corneal endothelium (see Figure 3) and non-granulomatous if these concretions are small.

The most common symptoms of uveitis are blurred vision, pain, floaters, light sensitivity, and redness. The pain and redness are typically seen in acutely inflamed eyes, and may not be prominent in eyes with asymptomatic, chronic inflammation or for inflammation that is solely posterior to the lens. The main causes of blurred vision are media opacity from the inflammatory reaction, cataract, secondary glaucoma, and macular edema. Ophthalmologists grade and classify uveitis by severity of the inflammatory reaction and the location of ocular involvement (See table 2.)

Acute Anterior Uveitis: Spondylarthropathies

Spondylarthropathies, such as ankylosing spondylitis and reactive arthritis, are the most common identifiable causes of anterior uveitis. In North America, approximately 50% of patients with anterior uveitis are HLA-B27 positive. The typical patient presents with sudden onset of acute anterior uveitis (AAU) in one eye (see Figure 4), but this condition can subsequently recur in either eye. Simultaneous bilateral involvement is not typical. Posterior segment inflammation is generally uncommon. Most cases resolve completely within several months.3

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS): Iritis is sometimes the first clue to the presence of an associated spondylarthritis. In some patients, the inflammation can be severe enough to produce hypopyon, fibrin formation, and posterior synechiae. AAU occurs in 25% to 40% of patients with AS, and AS can be diagnosed in 18% to 34% of patients with AAU. The prognosis of AAU associated with AS is generally good; each acute attack usually responds to topical corticosteroid drops with or without cycloplegics. If promptly treated, this disease usually does not result in any residual damage to the eye.4,5

Reactive arthritis: HLA-B27–positive patients with an enthesitis also may develop episodes of AAU similar to that which occurs in patients with AS. Conjunctivitis can be seen at the early stage of the disease and acute nongranulomatous iritis occurs in approximately 40% of patients. In atypical cases, the uveitis becomes chronic, bilateral, and/or intermediate.6

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): Ocular inflammation occurs in approximately 4% to 6% of patients with IBD. The most common forms of ocular involvement are uveitis and scleritis. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are both associated with uveitis. A common presentation of ocular disease resembles that which occurs in AS with nongranulomatous, recurrent, unilateral, acute anterior uveitis. Unlike AS, however, patients with IBD can have the insidious onset of a chronic, bilateral uveitis. Posterior segment involvement—including pars plana exudates, vitreous inflammation, and retinal vasculitis—has occasionally been reported.

Approximately half of patients develop uveitis prior to onset or diagnosis of IBD. The activity of uveitis does not often parallel the gastrointestinal disease activity, but scleral inflammation may. Uveitis is strongly related to sacroiliitis and arthritis. Of patients with IBD, 20% may have sacroiliitis; of these patients, 60% are HLA-B27–positive. Patients with IBD who have acute iritis tend to be HLA-B27–positive and have sacroiliitis. In contrast, patients with IBD who develop sclerouveitis tend to be HLA-B27–negative and have no sacroiliitis.7,8

Psoriatic arthritis: AAU is associated with psoriatic arthritis. An association between uveitis and psoriasis without arthritis has been reported. Eye involvement associated with psoriatic arthritis includes conjunctivitis, anterior uveitis, and scleritis. Like patients with IBD, patients with psoriatic arthritis often have nongranulomatous, recurrent anterior uveitis, but insidious chronic bilateral inflammation has frequently been reported as well.9

Acute Anterior Uveitis: TINU Syndrome

Although most rheumatologists are unfamiliar with the tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome, the disease is more common than generally appreciated. Importantly, the clinical manifestations, which include fever, arthralgias, and fatigue in association with a markedly elevated sedimentation rate, can be confused with many autoimmune processes. The most common ocular manifestation of the TINU syndrome is bilateral, sudden-onset, anterior uveitis. The disease can present in one eye initially, with the second eye becoming clinically involved within four months.

TINU has been found in 10% of patients with bilateral, sudden-onset anterior uveitis; the percentage jumps to 32% in patients under 20. The onset of renal disease may precede or simultaneously present at the onset of uveitis. Renal disease following ocular involvement is less common. The course of uveitis is persistent in most patients, with a median duration of seven months. While some patients can have chronic uveitis for years, patients generally achieve excellent visual prognosis and good renal function with limited use of topical and short-course oral corticosteroids.10

Chronic Anterior Uveitis: JIA

Inflammation of the anterior segment that persists longer than three months is termed “chronic anterior uveitis.” Some experts also use the term “chronic” to mean the opposite of acute (“chronic” is sometimes equated with insidious onset). Because insidious onset of inflammation is typical of the eye disease among children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), some patients are asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed in a school screening examination.

JIA is the most common systemic disorder associated with iridocyclitis in children. Among the subsets of JIA, the vast majority of patients who have uveitis are in the pauciarticular group. The average age of onset of uveitis is six. Uveitis generally develops within five to seven years of the onset of joint disease but may occur as long as 28 years after the development of arthritis. Ocular inflammation is not related to joint disease activity. Girls with pauciarticular disease and a positive antinuclear-antibody test are at high risk to develop chronic uveitis. Most patients have a negative rheumatoid factor.11

Because of the frequently asymptomatic nature of the uveitis, profound ocular damage can occur silently. According to guidelines developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, children with polyarticular and pauciarticular JIA should undergo regular slit-lamp examinations at least every six months. Those who are younger than seven and antinuclear antibody–positive should see an ophthalmologist every three to four months. Those with Still’s disease should have an eye exam annually.12

Intermediate or Panuveitis

Behçet’s syndrome: Behçet’s syndrome is a generalized occlusive vasculopathy of unknown cause. Its classic triad consists of acute iritis with hypopyon, painful oral ulcers, and genital ulceration. The disease is most common in Southeast Asia, the Eastern Mediterranean to Japan, and less common in the United States. In Asians, it is associated with HLA-B51.

Although Behçet’s syndrome may cause panuveitis, a characteristic feature of this disease is recurrent acute iritis or chronic iridocyclitis. This complication is often bilateral and can be associated with a transient hypopyon. Posterior segment involvement includes retinal vasculitis, retinal hemorrhages, macular edema, focal retinal necrosis, ischemic optic neuropathy, and vitritis.

Treatment of Behçet’s syndrome includes the initial use of oral corticosteroids. Early institution of immunosuppressive medication improves long-term prognosis. Azathioprine and cyclosporine have been shown to be useful treatments in randomized controlled trials. Infliximab and alpha-interferon have shown utility in open-labeled studies. The disease tends to be chronic and recurrent, and—if unsuccessfully treated—can lead to blindness with eventual ischemic retinopathy and optic atrophy.13

Lyme disease: Ocular involvement in Lyme disease occurs at all stages. An early sign is follicular conjunctivitis. Uveitis associated with Lyme disease is rare but could manifest as a chronic iridocyclitis or vitritis.14

Sarcoidosis: Up to half of patients with systemic sarcoidosis exhibit ocular inflammatory diseases and uveitis is the most common ocular manifestation. In most series, sarcoidosis accounts for 3% to 10% of all patients with uveitis evaluated at a referral center.

Sarcoidosis can cause chronic granulomatous iridocyclitis. Typical findings are large keratic precipitates, iris nodules, and white clumps of cells in the inferior anterior vitreous. Iris nodule and posterior synechiae can lead to secondary glaucoma. Posterior segment involvement is less frequent. Small granulomas along retinal venules can be useful in diagnosis. Macular edema and optic disc involvement lead to visual loss. A retinal vasculitis is associated with sarcoidosis even though vasculitis is not typical of this disease in other organs. Ocular disease activity may not parallel other organ manifestations.15

Blau syndrome (familial granulomatous arthritis): Mutations in the human NOD2/CARD15 gene cause Blau syndrome, characterized by granulomatous uveitis, arthritis, and rash. Blau syndrome is an autosomal-dominant disease. Skin rash is usually a prominent initial manifestation, which can be observed in early childhood as painless tiny tan dots. The joint anomalies always appear in the first decade, but do not lead to severe handicap until the fourth or fifth decade of life. Episodes of uveitis tend to recur, and progress to posterior involvement. Uveitis can be associated with disc edema, retinal striae, and secondary glaucoma. Blau syndrome can be mistakenly diagnosed as childhood-onset sarcoidosis, but lack of lung involvement and the mode of inheritance are clues for differentiation.16

Other Rheumatologic Diseases That Cause Uveitis

Cogan’s syndrome: Patients with Cogan’s syndrome present with ocular and audiovestibular symptoms, which typically occur within two years of each other. The most common ocular involvement is bilateral, non-syphilitic interstitial keratitis. Atypical cases can present with scleritis, uveitis, retinitis, and optic neuritis. Audiovestibular symptoms resemble Ménière’s disease. Deafness occurs in about 50% of patients. Systemic manifestations include fever, arthritis, skin rash, lymphadenopathy, gastrointestinal symptoms, neurologic abnormalities, and cardiovascular involvement. Systemic corticosteroids with or without immunosuppressive therapy are often effective in controlling ocular and other visceral manifestations, but have limited success in restoring hearing.17

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): Ocular involvement with SLE includes dry eye syndrome, keratitis, scleritis, eyelid lesions, and (rarely) uveitis. The most common intraocular findings are retinal microvascular abnormalities, including cotton-wool spots, retinal arteriolitis, vascular occlusion, and vitreous hemorrhage. The presence of retinal vasculitis and neovascularization often correlates with central nervous system involvement and antiphospholipid antibodies.18

Polyarteritis nodosa: Ocular involvement is rare in polyarteritis nodosa, but includes scleritis, uveitis (iritis and vitritis), hypertensive retinopathy, and retinal vasculitis. Cotton-wool spots and retinal hemorrhages can also be seen. Central retinal artery occlusion and optic atrophy may lead to blindness in the late stage of disease.19

Wegener’s granulomatosis: Eye disease affects 50% of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Common eye findings include orbital inflammation, scleritis, and keratitis. Uveitis as a primary involvement is uncommon. Patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis may develop scleritis as the initial manifestation. Patients with scleritis and a positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test tend to have severe scleritis, even if other signs of Wegener’s granulomatosis are absent. Posterior scleritis may cause visual loss and ocular pain with exudative retinal detachment. Retinal vasculitis and true retinitis are rarely reported.20,21

Other diseases that cause both uveitis and arthritis include Whipple’s disease, relapsing polychondritis, neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease, and Kawasaki’s disease.

Medical Treatment of Immune-mediated Uveitis

Most experts in the treatment of uveitis rely on a pyramidal approach to the inflammation. The levels in the pyramid as used in our practice are:

Topical corticosteroids: Topical corticosteroid therapy, such as prednisolone acetate, is used to treat anterior uveitis. Initial administration is usually frequent, with gradual tapering when inflammation subsides. The major side effects include increased intraocular pressure and cataractogenesis.

Topical cycloplegics: Cycloplegics help relieve photophobia and pain, secondary to ciliary spasm. They prevent or sometimes break synechiae formation. They are usually used in active anterior uveitis. Some of the options to dilate the pupil include cyclopentolate, scopolamine, and atropine. While these are usually well tolerated, cycloplegics should be used with caution in children and elderly patients. Potential but rare systemic side effects include fever, tachycardia, seizure, and hallucinations. Patients with a dilated pupil have difficulty with near vision such as reading and may be especially sensitive to sun.

Local corticosteroids injection and intraocular sustained released implant: Periocular corticosteroid injections are useful in acute, recalcitrant, or noncompliant cases as an alternative to frequent eye drops. They are also particularly helpful when posterior segment involvement such as macular edema occurs. Periocular injection is effective 70% of the time, but intravitreal injection is an alternative if the clinical benefit proves inadequate. Use intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection to treat macular edema from uveitis. Surgical implantation of a sustained-released device is an option for chronic persistent inflammation. A fluocinolone implant is Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–ap-proved and delivers corticosteroid into the vitreous cavity for 30 months. The main adverse effects are similar to those of topical corticosteroid treatment, but one more common and severe.

Systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents: Oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of uveitis therapy. For the patient whose condition is not adequately controlled by topical corticosteroids or local therapy, immunosuppression may be required to combat vision-threatening inflammation, inadequate response to corticosteroid treatment, and corticosteroid intolerance. Drugs options include antimetabolites (i.e., methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil), calcineurin inhibitors (i.e., cyclosporine and tacrolimus), and alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil).22

Biologics: TNF inhibitors, alpha interferon, and daclizumab (anti–IL-2 receptor alpha chain) have been studied for the treatment of uveitis. Of the TNF inhibitors, infliximab has proven dramatically effective for several manifestations of Behçet’s disease, and some argue that it is the drug of choice for this indication.23 On the basis of retrospective data, several centers have concluded that infliximab is more effective than etanercept in the treatment of uveitis.24

Our personal experience in a prospective study of infliximab for various types of refractory uveitis demonstrated marked efficacy as well as unexpected toxicity. Among 31 studied patients, side effects included three cases of drug-induced lupus and three thromboses (two with pulmonary emboli and one with myocardial infarction). While this study is too small to conclude that patients with uveitis are especially susceptible to toxic effects from infliximab, we speculate that patients who have localized inflammation may be more prone to adverse events from systemic inhibition of a cytokine.25

TNF inhibitors reduce the frequency of uveitis in patients with AS who are prone to recurrent bouts of eye inflammation.

To date only one report has addressed the efficacy of adalimumab for uveitis. Although this report is favorable, greater study is needed before this approach is adopted widely.

Our approach is to recommend a TNF-inhibitor in the form of a monoclonal antibody for patients with uveitis who have failed other immunosuppressives and who have a systemic disease such as a spondylarthropathy that should respond to this approach. Ironically, although infliximab is not FDA-approved for JIA, high doses of infliximab are reportedly effective for the uveitis associated with JIA.

Experience using rituximab for uveitis is limited and many other biologics, such as abatacept and alefacept, are essentially unstudied. An open-label study using rituximab for scleral and orbital disease is currently underway at our institution.

Conclusion

While rheumatologists and ophthalmologist often speak a different language, they share a mutual responsibility for patients with systemic illness whose vision requires their combined efforts. An understanding of the ocular manifestations of rheumatic disease enables a rheumatologist to have the gratifying opportunity to protect or restore vision in a subset of patients with sight-threatening inflammation.

Dr. Pasadhika is a fellow in the ophthalmology department at Casey Eye Institute and an instructor in the ophthalmology department at Chulalongkorn University Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. Dr. Rosenbaum is professor of medicine, ophthalmology, and cell biology and director of inflammation research at OHSU and director of the Uveitis Clinic at Casey Eye Institute.

References

- Hamideh F, Prete PE. Ophthalmologic manifestations of rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2001;30:217-241.

- Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT; Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509-516.

- Martin TM, Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. Anterior uveitis: current concepts of pathogenesis and interactions with the spondyloarthropathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14:337-341.

- Power WJ, Rodriguez A, Pedroza-Seres M, et al. Outcomes in anterior uveitis associated with the HLA-B27 haplotype. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1646-1651.

- Tay-Kearney ML, Schwam BL, Lowder C, et al. Clinical features and associated systemic diseases of HLA-B27 uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:47-56.

- Kiss S, Letko E, Oamruddin S, et al. Long-term progression, prognosis, and treatment of patients with recurrent ocular manifestations of Reiter’s syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1764-1769.

- Ghanchi FD, Rembacken BJ. Inflammatory bowel disease and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;46:663-676.

- Salmon JF, Wright JP, Murray AD. Ocular inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:480-484.

- Paiva ES, Macaluso DC, Edwards A, et al. Characterisation of uveitis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:67-70.

- Mackensen F, Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. Enhanced recognition, treatment, and prognosis of tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:995-999.

- Cunningham ET. Uveitis in children. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000;8:251-261.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Rheumatology and Section on Ophthalmology. Guidelines for ophthalmologic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 1993;92:295-296.

- Evereklioglu C. Current concepts in the etiology and treatment of Behçet disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50:297-350.

- Zaidman GW. The ocular manifestations of Lyme disease. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1997;37:13-28.

- Jones NP. Sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:393-396.

- Rose CD, Wouters CH, Meiorin S, et al. Pediatric granulomatous arthritis: an international registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3337-3344.

- Grasland A, Pouchot J, Hachulla E, et al. Typical and atypical Cogan’s syndrome: 32 cases and review of literature. Rheumatology. 2004;43:1007-1015.

- Arevalo JF, Lowder CY, Muci-Mendoza R. Ocular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:404-410.

- Akova YA, Jabbur NS, Foster CS. Ocular presentation of polyarteritis nodosa. Clinical course and management with steroid and cytotoxic therapy. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1775-1781.

- Pakrou N, Selva D, Leibovitch I. Wegener’s granulomatosis: ophthalmic manifestations and management. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:284-292.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Foster CS, et al. Guidelines for the use of immunosuppressive drugs in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders: recommendations of an expert panel. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:492-513.

- Lim L, Suhler EB, Smith JR. Biologic therapies for inflammatory eye disease. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34:365-374.

- Theodossiadis PG, Markomichelakis NN, Sfikakis PP. Tumor necrosis factor antagonists: preliminary evidence for an emerging approach in the treatment of ocular inflammation. Retina. 2007;27:399-413.

- Suhler EB, Smith JR, Wertheim MS, et al. A prospective trial of infliximab therapy for refractory uveitis: preliminary safety and efficacy outcomes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:903-912.