The role of ANCA in disease pathogenesis remains unclear. Support for a pathogenic role for ANCA has come from in vitro data indicating potential mechanisms through which ANCA-mediated vascular injury could occur and from an elegant MPO knockout mouse model.5 These experiments demonstrated the induction of glomerulonephritis and vasculitis by the adoptive transfer of mouse-anti-MPO splenocytes into immune-deficient mice or the passive infusion of mouse anti-MPO immunoglobin G into both immune-deficient and immune-competent mice. However, the absence of ANCA in up to 20% of patients with WG and the ability for patients to have high ANCA levels yet remain in remission argue against ANCA being pathogenic.

Disease Activity

Assessment of disease activity forms the foundation for treatment decisions. In the absence of an effective biomarker, collective information from the history, physical examination, laboratories, and imaging remain the best means of detecting active disease. Although instruments such as the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) for WG are not generally used outside of studies, they highlight the manifestations of active disease in WG.6 It should always be kept in mind that many features, in particular pulmonary infiltrates or hematuria, are not specific for active WG, and the potential for chronic damage, infection, or medication toxicity must always be considered.

Treatment

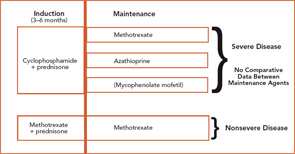

The current therapeutic approaches to WG are shown in Figure 1 (above).7 Treatment of WG is considered to have two phases: induction, where active disease is put into remission; and maintenance, where remission is sustained. CYC-sparing approaches have been developed to use this effective agent optimally for the treatment of severe disease while limiting CYC exposure to reduce the risk of toxicity.8

Induction

To date, the only agents proven to induce remission of active WG are prednisone in combination with either CYC or MTX. Patients with severe disease are usually treated with CYC 2 mg/kg/day and prednisone 1mg/kg/day. CYC should be given as a single dose in the morning with a large amount of fluid throughout the day to maintain a dilute urine. Because CYC is excreted by the kidney, dose reduction should be considered in patients with renal insufficiency. CYC treatment should be limited to three to six months in almost all instances, with subsequent transition to a maintenance agent.

The utility of daily oral versus intermittent intravenous (IV) CYC remains controversial, and the results from a randomized trial are not yet available. Although use of IV CYC has been based upon the rationale of side-effect reduction, it is not clear that the toxicity is less than daily CYC when given for three to six months combined with close monitoring.