For many adult rheumatologists, pediatrics is a distant memory from medical school, a field whose unusual syndromes, confusing vaccination schedules, and alarmingly small, noisy, and vulnerable subjects were left behind with relief years ago. Yet some of those patients—perhaps one in a thousand—will develop inflammatory arthritis and need the help of rheumatologists. In many centers, pediatric rheumatologists are not readily available, and adult rheumatologists are called to step in. Further, with rare and unfortunate exception, these children with arthritis grow up to adulthood, and many will need ongoing rheumatologic care. This brief review is a primer for adult rheumatologists facing such patients. The good news is that the similarities between pediatric and adult arthritis vastly outweigh differences. The challenge is that there are differences, and some of these are important. The focus of this review is to highlight these distinctions.

What Is Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis?

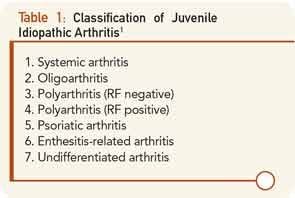

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the umbrella term used to characterize all types of inflammatory arthritis that arise without known cause before the 16th birthday. The term “JIA” was adopted to help resolve confusion stemming from two preexisting nomenclature systems, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) and juvenile chronic arthritis (JCA), though the former abbreviation remains in widespread use. JIA encompasses several different phenotypes (see Table 1).1

Oligoarticular JIA (oligo-JIA) is arthritis that involves fewer than five joints in the first six months of disease. This subtype is the most common, and is the disease that accounts principally for the remarkable epidemiological peak in JIA incidence between years one and four of life.

Polyarticular JIA (poly-JIA) by definition involves five joints or more in the first six months. A subset of poly-JIA patients have positivity for either rheumatoid factor or cyclic citrillunated peptide (CCP). Clinically, these patients are indistinguishable from those with adult seropositive rheumatoid arthritis.

Systemic JIA (sJIA) is a very distinct subset characterized by fever and rash, and commonly referred to under the eponym Still’s disease. Psoriatic arthritis is also recognized as a JIA subset, while other spondylarthropathies are gathered together under the term “enthesitis-related arthritis” (ERA).

Don’t Get Hung Up on JIA Subtypes

Aside from sJIA, which is unmistakably distinct, and arthritis involving the spine and sacroiliac joints, which, as in adults, requires different therapy than peripheral arthritis, the distinctions imposed by this nomenclature are of limited clinical value. Neither genome-wide association studies nor peripheral gene expression studies, nor detailed clinical phenotyping provide solid support for the current subdivisions.2 Correspondingly, therapeutic trials in JIA have most commonly enrolled by polyarticular course, rather than by JIA subtype (i.e., onset pattern). This is not quite to say that “anything goes” with respect to disease phenotypes, however. In particular, fever is characteristic of sJIA but is not part of the phenotype of any other JIA subtype. In other contexts, fever accompanying joint swelling may reflect infection, lupus, or cancer.

What’s Different about Diagnosing JIA?

Adult rheumatologists are used to diagnosing arthritis, and have developed the physical examination of the joints to a fine skill. This skill remains the core of arthritis diagnosis in children as well. Yet, there are some important differences. In adults, the history is at least as important as the examination. Do the joints hurt? Is there loss of function? Is there morning stiffness? Was there preceding trauma? These questions are important since the exam can be obscured by concurrent osteoarthritis and accumulated asymmetry due to injuries, while tenderness can have both inflammatory and noninflammatory causes. In children, symptom history is often limited, especially in the very young—recall that the peak age of onset of JIA is one to four years old. Young children localize pain remarkably poorly, and the complaint of pain is often minimal or even absent altogether.3 Rather, the extent and distribution of joint inflammation must be ascertained by meticulous examination of the whole skeleton, recognizing that children do not always acknowledge tenderness in inflamed joints. Fortunately, children’s joints are generally unaffected by prior injury, simplifying the detection of mild asymmetry that may indicate active or past synovitis.

The examination of the pediatric arthritis patient is different in several other ways. Since inflammation can affect skeletal growth, asymmetry in limb length (especially in the legs) can be an important clue to the presence and chronicity of arthritis. Further, JIA has a predilection to involve the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), potentially with devastating cosmetic consequences. TMJ arthritis in the young child, especially before four years of age, can injure the mandibular growth center adjacent to the articulating condyle, leading to permanent growth impairment and progressive micrognathia. This joint is difficult to examine, and since involvement is rarely symptomatic, any asymmetry in jaw opening must be pursued aggressively (for example, using gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) to permit rapid diagnosis and treatment.

Laboratory studies are also typically less informative in children, and may even be misleading. In adults, rheumatoid factor (RF) and especially CCP assays “nail” the diagnosis in at least half of arthritis patients. Further, most untreated adult arthritis patients will have measurable markers of systemic inflammation. Neither is the case in children. RF and CCP are present in less than 10% of JIA patients, and then only in older (usually >10-year-old) patients whose disease is usually obvious. Many oligo-JIA patients will have no abnormalities on blood examination, aside perhaps from a low-titer ANA. Therefore, even more than in adults, the diagnosis of JIA is established by exam, supplemented where indicated by tests such as Lyme serology to exclude alternate diagnoses.

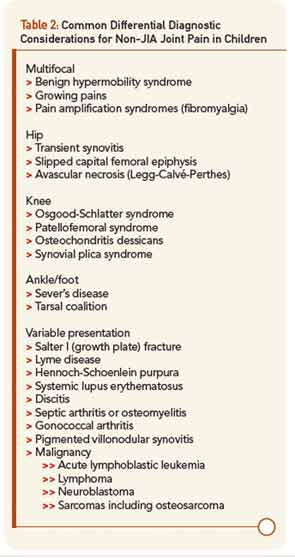

Yet, the biggest difference in diagnosis between pediatric and adult arthritis lies elsewhere: the differential diagnosis (see Table 2. In an adult with joint pain, the major alternatives are usually osteoarthritis, crystalline disease, overuse injuries such as tendonitis or bursitis, and pain amplification syndromes. While patellofemoral syndrome is common in both children and adults, as is pain amplification beginning in early adolescence, most of these other diagnoses are extremely rare in childhood. Their place in the differential diagnosis is assumed by benign hypermobility syndrome, growing pains, transient synovitis of the hip, and diseases specific for the immature skeleton. These latter include Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (avascular necrosis) of the hip, Osgood-Schlatter syndrome (tibial tuberosity apophysitis) at the knee, and Sever’s disease (calcaneal apophysitis) at the ankle.

Of greatest clinical concern are diseases affecting the growth plates, which in children may be more vulnerable to injury than ligaments and calcified bone. By far the most important of these is slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), in which the growth plate of the head of the femur is disrupted leading to anatomic deformity, avascular necrosis, and early hip osteoarthritis. Pain in SCFE is often referred to the knee, so even more than in adults, if the knee hurts, be sure to examine the hip, too. Overall, when evaluating a child with musculoskeletal issues, remember than most of what hurts is not arthritis, while arthritis may not seem to hurt much at all, presenting instead as functional limitation such as limp.3

A word about pain amplification syndromes (the fibromyalgia family). These syndromes are at least as prevalent in the adolescent population as true arthritis.3 As in adults, suspect pain amplification when symptoms and functional limitation are greatly out of proportion to physical and laboratory findings. In the pediatric population, such dysfunction typically presents as school absenteeism. An adolescent with joint pain, fatigue, normal labs, and months of school absence is highly unlikely to have JIA and much more likely to have pain amplification, potentially complicated by issues such as learning disabilities, bullying, depression, and physical or sexual abuse. As in adults, a positive diagnosis spares unnecessary testing and intervention while opening the way to appropriate therapy.

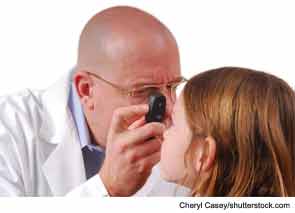

Don’t Forget the Eyes!

For reasons that remain unknown, JIA may be accompanied by destructive inflammation of the eyes, termed chronic anterior uveitis. The major risk factors are young age at onset and a positive ANA titer at any level above normal, with a risk peaking in excess of 30% in some subgroups. Ocular inflammation is usually clinically invisible without a slit lamp, and young children and parents will not notice the problem even as the eye is developing irreversible scarring injury. Therefore, ophthalmological screening should be part of the initial evaluation of suspected JIA, and should continue every three to 12 months depending on risk factors, since the prognosis of the eye depends on the presence or absence of scar at the time uveitis is diagnosed.4 Patients with sJIA, RF-positive poly-JIA, and ERA are generally less susceptible to this complication, though patients with ERA may develop acute anterior uveitis.

Treatment of JIA

The treatment of JIA is fundamentally similar to that of adult arthritis. Pediatric rheumatologists use the same agents, largely for the same indications and in the same way. There are, however, a few key differences.

In children with JIA, extinction of inflammation is the only acceptable therapeutic outcome. In adults, we sometimes tolerate low-grade disease when it appears nonerosive, and/or the patient chooses to avoid or will not tolerate additional therapy. This is essentially never acceptable in children, because inflammation affects the morphology of the growing skeleton, and injury to cartilage leads to osteoarthritis in early adulthood. I direct a clinic, described further below, that includes many adults with JIA who have limiting osteoarthritis in their twenties and thirties due to incomplete arthritis control as children. In many cases, these patients report that their arthritis symptoms had seemed adequately managed, often on nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) alone, though careful history usually indicates that they still had low-grade or episodic swelling.

Fortunately, children are especially tolerant of our medications. A problematic tendency of adult rheumatologists is to “undershoot” when treating children, out of the concern—often echoed by parents—that children might be especially vulnerable to adverse drug effects. In fact, the opposite seems to be the case. Pediatric rheumatologists use per-kilogram doses of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) typically well in excess of those tolerated by adults. In part, this is because pharmacokinetics differ in children in favor of more rapid clearance and because comorbid factors such as diabetes, obesity, alcohol exposure, and concomitant polypharmacy are usually absent. This principle is clearly stated in the recent ACR guidelines for JIA treatment, in which DMARDs and even biologics are considered first-line therapeutics in many children with JIA. By contrast, an extended NSAID trial is generally inappropriate.5 Aggressive up-front therapy may be particularly helpful in sJIA, where a go-slow approach often results in protracted steroid exposure and substantial morbidity.6 When in doubt, a phone consultation with a pediatric rheumatologist, or having the patient travel to visit the nearest JIA specialist, may help to optimize long-term outcome.

Will JIA Go Away?

It is frequently assumed that children will “outgrow” JIA, and in some cases this does occur. Surprisingly, high-quality long-term outcome data are not available, so our prognostic capacity is strikingly limited.7 Published series suggest that up to 75% of patients with classic early-onset persistent oligoarticular arthritis may attain long-term drug-free remission. The prognosis for the other subtypes is less rosy. RF-positive poly-JIA is, like adult RA, almost always a lifelong disease requiring treatment indefinitely. A fraction of seronegative poly-JIA patients, perhaps 20%–30%, enter long-term drug-free remission, but the majority will require therapy long term. Among patients with sJIA, perhaps half attain drug-free remission. Overall, remissions in JIA are unpredictable and are not influenced by puberty.

It is, therefore, a particular challenge to decide whether and how to discontinue therapy in a patient in remission on DMARDs. A key prospective study recently examined this question in patients with JIA in remission on methotrexate. After discontinuation of therapy, more than half flared over the ensuing two years. Some of these patients had elevated inflammatory markers using very sensitive assays, suggesting that they were probably not really in full remission after all, but others did not, and no clinical, demographic, or laboratory features could fully distinguish patients who flared from those who did not.8,9 Compounding the problem, some patients who flare after discontinuation of methotrexate cannot be “recaptured” on the same regimen, but may need addition of biologics to regain control, if indeed control can be established. Discontinuing therapy is, therefore, not without risk.

Transitioning to Adult Rheumatology

Based on these prognostic considerations, it is evident that many—if not most—children with JIA will need ongoing care as adults. Transition of care can be difficult for patient and providers alike. The barriers are several, and ideally, they should be addressed by pediatric rheumatologists well before the time of transfer.7,10 These barriers include attachment to long-time providers, lack of familiarity with the new provider and institution, the need to establish care not only in rheumatology but also in primary care and sometimes in other subspecialties, and the culture shock associated with moving from a family-centered care model to one in which the patient bears most of the responsibility. Medical records are usually transferred incompletely. Insurance changes may arise. All told, transition is a difficult period with a clear risk that important details, or even the patient himself or herself, may fall between the cracks.

At the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, we addressed this need by forming the Center for Adults with Pediatric Rheumatic Illness (CAPRI), which has become the transfer destination of the majority of pediatric rheumatology patients remaining in Boston after completing care at Boston Children’s Hospital. Some of these patients are cared for long term in CAPRI, while others are transferred to other providers—for example, the Brigham Lupus Center—once the transition has been accomplished successfully. Having directed CAPRI since its foundation in 2005, I have come to several conclusions with respect to such transitioning patients.

First, well-worn pathways for patient transition are important. At our adult hospital, out of more than forty rheumatology faculty members, only two handle the majority of these transfers—myself, as a rheumatologist trained in both the pediatric and adult medicine and rheumatology, and my colleague Derrick Todd MD, PhD, who spent several years working in CAPRI as a rheumatology fellow. Maintaining a single pathway for transition breeds familiarity and collegiality between pediatric and adult providers. Further, our CAPRI fellows and staff have particular knowledge and interest in pediatric rheumatic illnesses, something that patients recognize and that inspires trust and confidence. Having access to musculoskeletal ultrasound in the clinic facilitates the advanced imaging of involved joints without the need for ionizing radiation in adolescents and young adults.

Second, access to prior medical records is critical. In our center, this process is greatly facilitated through my concomitant staff appointment at Boston Children’s Hospital, our major referring center. More challenging has been the transition of patients who received care in other pediatric rheumatology centers, where we have no direct access to medical records. In these instances, contact with referring pediatric rheumatologists becomes especially important, since transferring patients often have a long history of studies and therapeutic attempts that the patient and family may remember only dimly.

In children with JIA, extinction of inflammation is the only acceptable therapeutic outcome.

Third, transition is a gradual process. Patients are usually accompanied by a parent at the first visit, and depending on the individual, parents may continue to come for some time. But they do not come forever, and we have not found it necessary to exclude parents at any specific point. By communicating directly with the patient, and indicating in various ways (such as addressing the patient as Mr. or Ms.) that the patient is expected to run the show, patients gradually assume responsibility. The timeframe over which this transition occurs varies markedly from individual to individual, in parallel with emotional maturation that often progresses into the mid-twenties. For patients in whom compliance and other issues pose a particular difficulty, we work closely with a CAPRI-affiliated social worker and nurse to provide optimal care.

An issue of particular difficulty in transitioning patients relates to addressing vocational failure. Career aspirations are typically formed in early adolescence. When this period is spent focusing on illness, opportunities pass by and can be difficult to recapture later. Pediatric rheumatologists, and other pediatric providers, need to help ensure that transitioning young adults are ready not only for adult care but also for adult life.7

Our CAPRI model is only one of many possibilities. For example, in Vancouver, British Columbia, pediatric rheumatology patients are referred around age 18 to the Young Adults with Rheumatic Diseases (YARD) clinic, directed by Lori Tucker, MD, and David Cabral, MBBS, where pediatric and adult rheumatologists work together to prepare patients for transfer to the adult clinic by age 22.11 Both CAPRI and YARD are built around the skills, interests, and physical and financial/insurance resources available locally. To the extent that these differ from center to center, transition programs will invariably require considerable customization.

Specific Issues in Management of the Adult with JIA

By and large, the management of the adult with JIA differs little from that of the adult arthritic patient. These issues have been reviewed in detail.7 The agents used, and the dosages employed, are all identical. It does not appear that cumulative exposure through childhood substantially limits the ability to use DMARDs in this population. As in any patient with longstanding arthritis, the ability to discern active inflammation from pain and stiffness due to chronic joint injury can become difficult. Joint replacement is sometimes necessary, and should be deferred as long as tolerable given the limited lifespan of prostheses. However, it is important not to delay joint replacement beyond the “window of opportunity,” which may be limited by progressive loss of bone stock, joint contracture, and muscle wasting. Osteoporosis should be managed appropriately, since adults with JIA tend to have lower bone density than healthy adults, in particular if there was substantial steroid exposure during adolescence.

One particular issue unique to adult JIA is the management of uveitis. If the patient had uveitis as a child, it is prone to recur and regular ophthalmological care is indicated. If the patient never had uveitis, new onset in adulthood is extraordinarily unusual, to the extent that other diagnoses should be considered if it occurs. Further, should uveitis appear, an adult would typically notice symptoms, such as blurry vision, mild photosensitivity, and floaters. For this reason, while we discuss uveitis with our adult JIA patients, we no longer routinely screen patients without prior eye disease for uveitis.7

Conclusions

JIA is different from adult RA, but the differences are minor compared to the similarities. Making the diagnosis requires a particular sensitivity to the physical exam, whereas the history and laboratory studies may be less useful or even misleading. Surveillance of the eyes is essential to detect vision-threatening occult uveitis. Early and effective treatment is mandatory to ensure normal growth and function of the skeleton, and may require treatment strategies that are often more aggressive than those employed in adults. Since JIA persists into adulthood, in many patients, perhaps even the majority, adult centers need to be able to transition these patients and care for them long term. With appropriate education, this is a task for which adult rheumatologists are well prepared.

Dr. Nigrovic is a board-certified pediatric and adult rheumatologist and directs the Center for Adults with Pediatric Rheumatic Illness (CAPRI) at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He is assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:390-392.

- Henderson LA, Nigrovic PA. New directions in the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Int J Clin Rev. 2012;3:3.

- McGhee JL, Burks FN, Sheckels JL, Jarvis JN. Identifying children with chronic arthritis based on chief complaints: Absence of predictive value for musculoskeletal pain as an indicator of rheumatic disease in children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:354-359.

- Heiligenhaus A, Niewerth M, Ganser G, Heinz C, Minden K. Prevalence and complications of uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a population-based nation-wide study in Germany: Suggested modification of the current screening guidelines. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1015-1019.

- Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, et al. 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:465-482.

- Nigrovic PA, Mannion M, Prince FH, et al. Anakinra as first-line disease-modifying therapy in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Report of forty-six patients from an international multicenter series. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:545-555.

- Nigrovic PA, White PH. Care of the adult with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:208-216.

- Foell D, Wulffraat N, Wedderburn LR, et al. Methotrexate withdrawal at 6 vs 12 months in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in remission: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1266-1273.

- Gerss J, Roth J, Holzinger D, et al. Phagocyte-specific S100 proteins and high-sensitivity C reactive protein as biomarkers for a risk-adapted treatment to maintain remission in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1991-1997.

- McDonagh JE. Young people first, juvenile idiopathic arthritis second: Transitional care in rheumatology. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1162-1170.

- Tucker L. The YARD Clinic in Vancouver: An original! CRAJ. 2008;18:18-19.