In August 2001, Diane Endicott* noted the spontaneous onset of tightening of the skin over her feet and lower legs. Endicott was a 40-year-old woman with type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus which started at age 10 and stage 5 chronic kidney disease (kidney failure with glomerular filtration rate less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or receiving dialysis), who had been on hemodialysis for the previous two years. This skin tightening progressed rapidly to involve the skin on her thighs, hands, and forearms. It also involved the skin over her breasts and in her perineal region. She observed the skin in these areas to be thickened and tethered to the underlying tissue and darker in color than her skin elsewhere.

Her fingers became fixed in flexion. Her hands became claw-like, causing her difficulty buttoning her blouse, and she developed fixed flexion contractures of her knees. (See Fig. 1) Because she could not fully extend either leg, she no longer was able to walk independently and required the use of a wheelchair to move. She also developed conjunctival erythema and yellow scleral plaques. As her skin changes progressed to extend above her elbows, Endicott also developed fixed flexion contractures of her elbows and she became incapacitated by severe, burning pain in her extremities that kept her awake at night. However, she noted no tightening of the skin on her face and had never experienced color change of her digits upon cold exposure.

Endicott’s nephrologist was puzzled by the rapid onset of this scleroderma-like condition, having never seen this before among the other patients receiving dialysis under his care. To clarify Endicott’s diagnosis, he referred her to the rheumatology consultant at his hospital. The consultant had seen patients with scleroderma develop renal failure during scleroderma renal crisis. However, he, too, had never observed a patient with pre-existing stage 5 chronic kidney disease develop the new onset of cutaneous changes of scleroderma. Thus, he referred Endicott to a nearby academic medical center for dermatologic evaluation and for another rheumatologic opinion.

Early Cases

During the preceding four years, between May 1997 and November 2000, eight of 265 patients who had received renal allografts at Sharp Memorial Hospital in San Diego developed the relatively rapid onset of skin changes similar to Endicott’s and that resembled scleromyxedema. Each of these eight patients developed fibrotic skin changes on the trunk and extremities, which resulted in debilitating joint contractures. However, none developed facial involvement or had the circulating IgG lambda paraprotein that would be expected in scleromyxedema.1 Skin biopsies from each of these patients were sent to Philip E. LeBoit, MD, professor of clinical pathology and dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. Along with his fellow, Shawn E. Cowper, MD, now assistant professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., and other colleagues, he examined these biopsies and observed histologic features similar to one another but that were unique.

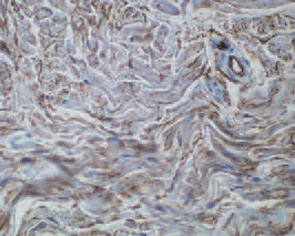

These features included thick reticular dermal collagen bundles surrounded by clefts, adjacent dermal fibrocytes that stained with antibodies to CD34 and antibodies to procollagen I, and increased amounts of dermal mucin. (See Fig. 1) In deeper biopsies, Dr. LeBoit and colleagues occasionally observed angiogenesis within the septae of fatty lobules.2 They concluded that each patient had developed a novel skin disease that they named nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy.3 Because fibrosis was subsequently observed in other organs, this entity has been renamed nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF).

Faced with a potential emerging epidemic, the California Department of Public Health invited the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to carry out an epidemiologic study of this novel skin disease. A case definition was established to identify patients who “developed large areas of hardened skin with slightly raised plaques, papules, or confluent papules with or without pigmentary alteration.” To confirm the clinical diagnosis, a skin biopsy demonstrating the novel characteristic histologic features was required.1

Unfortunately, the tragic events of September 11, 2001, forced the CDC to deploy its resources to other missions. By the time that Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report featured “Fibrosing Skin Condition Among Patients with Renal Disease” as the lead article in its January 18, 2002, issue, 49 cases had been identified in the United States and Europe.1

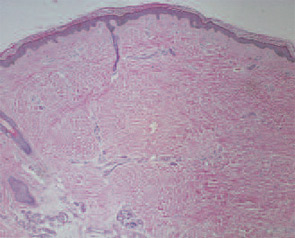

When Endicott presented for dermatologic and rheumatologic evaluation at the academic medical center, she underwent a wedge biopsy of the skin on her leg that demonstrated characteristic changes of NSF. At the time of her evaluation, no treatment attempted previously had resulted in significant improvement of skin changes in patients with NSF. These treatments included potent topical and systemic corticosteroids, histamine H2-receptor antagonists, cyclosporine, intralesional interferon-a, psoralen with ultraviolet A light treatment, and plasmapheresis.4-6

Upon the recommendation of the dermatology consultant, Endicott was treated with thalidomide. However, thalidomide therapy did not bring about significant improvement of her skin thickening, tethering, or hyperpigmentation. She continued to experience progressively worsening pain and limited function. Endicott’s blood pressure began to drop precipitously during hemodialysis treatments. Eventually, she chose to terminate hemodialysis and she died 22 months after the onset of her skin changes. Since her death, decreased skin thickening and improved joint mobility have been reported in three patients treated with extracorporeal photopheresis, in three patients treated with plasmapheresis, in two patients treated with pentoxiphylline, and in one patient treated with high dose intravenous immunoglobulin.6-9

Investigation into NSF Causes

Although NSF most notably involves the skin, tissue obtained during surgery and at autopsy has revealed systemic involvement. Examination of striated and cardiac muscles has demonstrated muscle fiber atrophy, perimysial and endomysial fibrosis, calcium deposition, scattered interstitial chronic inflammation, and endomysial deposition of collagen fibrils.10 In the lungs, mild interstitial fibrosis, thickening of the adventitia of small- and medium-size arterioles, and fibrosis of the pleura and diaphragm have been observed.11,12 Cardiac involvement also occurs, with fibrosis of the pericardium, great vessels, left ventricle, and interventricular septum.13 Fibrotic changes of the genitourinary tract and of the dura mater also have been observed.

All patients who developed NSF had abnormal renal function at some time before the onset of skin changes, although this was not required by the case definition.1 About half had undergone renal transplantation, which suggested that this condition was not caused by a specific type of renal replacement therapy and that it did not require renal failure to be present at onset. This observation raised the possibility that an environmental exposure might trigger the onset of NSF in patients with chronic kidney disease. A subsequent report by Swaminathan and colleagues suggested that patients with NSF had been exposed to higher doses of erythropoietin than control subjects.14 However, this observation was superseded by a key observation made by a very astute clinician in Austria.

Between 2003 and 2005, Thomas Grobner, MD, a nephrologist at the General Hospital of Wiener Neustadt, Austria, observed that five of nine patients receiving hemodialysis under his care developed skin changes of NSF within two to four weeks after undergoing magnetic resonance (MR) angiography with gadodiamide contrast.8 In contrast to the four patients who did not develop NSF after MR angiography, the five who developed skin changes had metabolic acidosis when the gadolinium-containing contrast agent was administered. Also, the five patients who developed NSF underwent hemodialysis for a longer time then those who did not, but Dr. Grobner found no other significant demographic differences between the two groups.

Shortly thereafter, Peter Marckmann, MD, of the department of nephrology, and colleagues from Copenhagen University Hospital at Herlev, Denmark, reported on 13 patients who also developed NSF following exposure to gadodiamide contrast during MR imaging.15 These patients developed skin changes between two and 75 days after exposure to a gadolinium-containing contrast agent. These reports and the report of seven additional patients prompted the Danish Medicines Agency to post an alert on its Web site on May 29, 2006, suggesting the possibility of a relationship between gadolinium exposure and the development of NSF.16

Guidelines for Using Gadolinium Contrast Agents in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients

- Do not administer intravenous gadodiamide to dialysis patients or to other patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease;

- Avoid double-dose (0.2 mmol/kg) or triple-dose (0.3 mmol/kg) studies;

- Exercise caution in administering gadodiamide to patients with acute renal failure;

- Screen patients scheduled for contrast-enhanced MRI examinations by obtaining a recent serum creatinine level and calculated creatinine clearance if they have a history of kidney disease or diabetes mellitus; and

- Check serum creatinine and calculated creatinine clearance in patients older than 60 years before gadodiamide administration.

Cases Mount and Understanding Grows

By 2006, more than 200 cases of NSF had been identified around the world.17 At Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, I had seen more than 25 patients with NSF confirmed by skin biopsy. To assess the prevalence of NSF among patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, my colleagues and I screened 186 patients receiving hemodialysis in five outpatient dialysis units in the Boston area for skin changes characteristic of NSF: hyperpigmentation, thickening, and tethering.18 We found that 25 (13%) of the 186 patients had cutaneous changes of NSF. Most strikingly, when we followed this cohort of patients for 24 months, we determined that the presence of cutaneous changes of NSF was associated with a three-fold increased risk of dying among patients receiving hemodialysis. Although the number of patients studied was too small to determine a specific cause of death, cardiovascular causes of mortality predominated. Thus, NSF is not only a condition that causes devastating symptoms, but it is also a disease associated with shortened lifespan.

Several groups have reported additional cases of NSF developing in patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease following exposure to gadodiamide contrast during MR imaging.19-21 When my colleagues and I examined a subcohort of 90 of the 186 patients that we had characterized, for whom active electronic medical records with records of radiologic studies were available, we found a strong association between prior exposure to gadolinium-containing contrast agents and the development of cutaneous changes of NSF. In this study, there was a relative risk of 10.7 for developing the skin changes after gadolinium exposure.18 In light of this new information, a re-review of Endicott’s hospital records revealed that she had undergone MR imaging with gadodiamide the month before she began to develop skin changes of NSF.

Gadolinium, a rare earth metal, is extremely toxic in its free form. When used as a contrast agent for MR imaging, gadolinium is chelated with one of several organic molecules that trap the gadolinium atom and prevent it from binding to tissues.22 Since 1988, five gadolinium-containing contrast agents have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in MR imaging in the United States. No contrast agent is approved for use in MR angiography. However, gadolinium-containing contrast agents have been used off-label for MR angiography with increasing frequency since 1997, and the appearance of NSF has coincided with this off-label use. Gadodiamide is the least stable of the five gadolinium-containing contrast agents that are available in the United States and therefore is the most likely one to release free gadolinium. Indeed, gadolinium has been detected in skin and blood vessels of patients with NSF who have received gadodiamide.23,24 A contrast agent administered by a radiologist is the only way a patient may be exposed to gadolinium.

Because there is not yet an effective medical treatment to reverse the changes of NSF, patients should receive physical therapy with active and passive range-of-motion exercises to improve or prevent worsening of existing joint contractures. Extracorporeal photopheresis, plasmapheresis, and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin are expensive modalities and available data do not support their consistent efficacy in treating NSF.

The strong association between NSF and prior exposure to gadolinium-containing contrast agents suggests that this condition might be prevented by not exposing patients with chronic kidney disease to gadolinium. Loma Linda University Medical Center (Calif.) has instituted and published a policy regarding the use of gadolinium-containing contrast agents in patients with chronic kidney disease.19 (See “Guidelines for Using Gadolinium Contrast Agents in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients,”)

Other institutions, such as mine, have adopted similar policies for all gadolinium-containing contrast agents. However, because NSF has also developed in several patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate 15 to 29 mL/min/1.73 m2), similar caution should be observed in all patients with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and possibly those with lesser degrees of renal dysfunction. Only prospective epidemiologic studies will define the level of renal function above which it is safe to administer gadolinium-containing contrast agents without the risk of developing NSF.

Future studies should be directed toward understanding the molecular mechanism by which fibrosis occurs following gadolinium exposure in patients with underlying chronic kidney disease and targeting that mechanism with specific therapies that will prevent development of and reverse fibrosis.

Dr. Kay is director of the Rheumatology Clinical Research Unit and associate clinical professor of medicine at the Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fibrosing skin condition among patients with renal disease – United States and Europe, 1997-2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:25-26.

- Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, Robin HS, LeBoit PE. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:383-393.

- Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, et al. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356: 1000-1001.

- Swartz RD, Crofford LJ, Phan SH, Ike RW, Su LD. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: a novel cutaneous fibrosing disorder in patients with renal failure. Am J Med. 2003;114:563-572.

- Hubbard V, Davenport A, Jarmulowicz M, Rustin M. Scleromyxoedema-like changes in four renal dialysis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:563-568.

- Baron PW, Cantos K, Hillebrand DJ, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosingdermopathy after liver transplantation successfully treated with plasmapheresis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003; 25:204-209.

- Gilliet M, Cozzio A, Burg G, Nestle FO. Successful treatment of three cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with extracorporeal photopheresis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:531-536.

- Grobner T. Gadolinium – a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(4):1104-1108.

- Chung HJ, Chung KY. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: response to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:596-597.

- Levine JM, Taylor RA, Elman LB, et al. Involvement of skeletal muscle in dialysis-associated systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy). Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:569-577.

- Jimenez SA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, et al. Dialysis-associated systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy): study of inflammatory cells and transforming growth factor beta1 expression in affected skin. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2660-2666.

- Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, Kurtz K. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:903-906.

- Gibson SE, Farver CF, Prayson RA. Multiorgan involvement in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: an autopsy case and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:209-212.

- Swaminathan S, Ahmed I, McCarthy JT, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and high-dose erythropoietin therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:234-235.

- Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2359-2362.

- The Danish Medicines Agency: Investigation of the Safety of MRI Contrast Medium Omniscan. Available at www.dkma.dk/1024/visUKLSArtikel.asp?artikelID=8931. Last accessed August 3, 2007.

- Cowper SE, Bucala R, Leboit PE. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy/nephrogenic systemic fibrosis – setting the record straight. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:208-210.

- Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik L, Kay J. Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis predict early mortality and are associated with gadolinium exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3433-3441.

- Broome DR, Girguis MS, Baron PW, et al. Gadodiamide-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: why radiologists should be concerned. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:586-592.

- Khurana A, Runge VM, Narayanan M, Greene, Jr. JF, Nickel AE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a review of 6 cases temporally related to gadodiamide injection (omniscan). Invest Radiol. 2007;42:139-145.

- Sadowski EA, Bennett LK, Chan MR, et al. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis: Risk Factors and Incidence Estimation. Radiology. 2007;243(1):148-157.

- Idee JM, Port M, Raynal I, et al. Clinical and biological consequences of transmetallation induced by contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging: a review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2006;20:563-576.

- High WA, Ayers RA, Chandler J, Zito G, Cowper SE. Gadolinium is detectable within the tissue of patients with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:21-26.

- Boyd AS, Zic JA, Abraham JL. Gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:27-30.