During a checkup, a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patient asks about the best diet to follow to help control RA symptoms—how do you respond? Although there are no clear-cut answers on what diet is most helpful, it is important to consider food choices, along with medication, exercise, and other factors, as part of each patient’s treatment plan.

With the voluminous diet choices and trends out there—Mediterranean, gluten-free, vegetarian, dairy-free, and plenty of other so-called nutritional “cure-alls” your patients can easily find online—it’s hard to advise RA patients on the best dietary choices.

Still, it’s a crucial topic to address as there are some patients who would prefer to try a natural approach before they take medications, says Scott Zashin, MD, a rheumatologist practicing in Dallas. Or, they want to follow a healthy diet that can help their RA along with the use of medications.

The idea of controlling arthritis through changes in diet appeals to many patients, says Richard S. Panush, MD, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology if the department of medicine at Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “The notion that today’s symptoms reflect what one ate yesterday—and that symptoms are therefore simple to control by eating certain foods and not others—is very seductive,” wrote Dr. Panush and co-authors in a recent publication on complementary and alternative medicine for RA.1

Discussing diet is also important because many patients with RA may have trouble buying or preparing meals, which could make them even more vulnerable to additional dietary restrictions, says Geir Smedslund, PhD, senior researcher at the National Resource Centre for Rehabilitation in Rheumatology in Oslo, Norway.

Despite evidence (or lack thereof) for an ideal RA diet, there are some drawbacks with using diet as a way to help RA symptoms. First, there’s limited scientific proof regarding the effectiveness of a dietary approach aimed to help RA, says Dr. Panush. Another drawback of a dietary approach is that it can be hard to follow in the long term, says Dr. Smedslund. This is something that Dr. Smedslund and fellow researchers pointed out in their 2010 review article on diet and RA, where they observed high dropout rates related to specific dietary trends.2

Even though a number of patients seem to have a genuine interest in improving their diet, that doesn’t mean that they’ll stick with it. “Rheumatoid patients are not necessarily more motivated than others to follow a certain diet because the treatments we have for them are so good,” says Dr. Zashin.

“Not too many people are following good dietary recommendations,” says Lona Sandon, MEd, RD, LD, assistant professor in the department of clinical nutrition at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas.

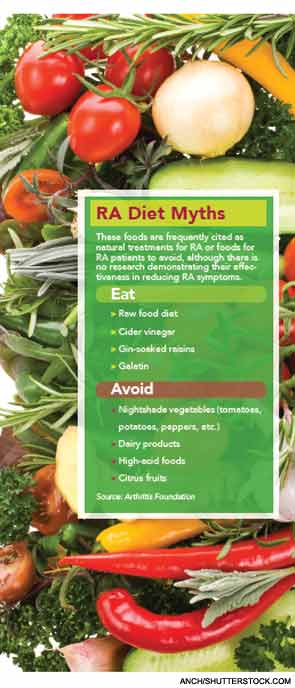

She sees some patients with RA who find information on the Internet that recommends eliminating gluten, dairy, “nightshade” plants (including healthy items such as potatoes, tomatoes, and peppers), and more. “There’s no solid evidence to support that,” she says. Such a diet is too restrictive and potentially unhealthy, says Sandon.

Although there may not be one be-all, end-all dietary approach to help those with RA beyond a generally balanced diet, there are still some reasons why the diet discussion might be an important one to broach with patients.

Considering Comorbidities

Excessive body weight. Cardiovascular disease. Osteoporosis.

These three health problems can be more common in RA patients—so even if the jury’s still out on the ideal RA diet, these comorbidities alone are enough reason to advocate for a balanced diet, says Sandon.

“A lot of people with RA are also obese. They need nutritional counseling because obesity aggravates RA,” she says.

Although Dr. Panush notes that there is no good, consistent evidence that certain foods or special diets can affect the symptoms of most people with RA, he does emphasize that extra weight can affect one’s joints. For this reason, he advocates a balanced, healthy diet with RA patients.

Then there’s heart disease, which is well known to be a higher risk for those with RA than the general population. An association between heart disease and RA was what prompted research on fruit and vegetable consumption led by Michael Crilly, MD, MPH, senior lecturer in clinical epidemiology at the University of Aberdeen Medical School in Aberdeen, Scotland. The study focused on arterial dysfunction in 114 patients with RA and how it correlated with daily fruit and vegetable consumption.3

“We found those with higher vegetable consumption had lower arterial dysfunction,” says Dr. Crilly. However, higher fruit consumption did not correlate to lower arterial dysfunction—a surprising finding, he says. Still, he and fellow researchers noted that the findings are consistent with the association between vegetables and nitrate along with the enterosalivary circulation of nitrate and its influence on arterial function. Dr. Crilly is working on new research with RA patients that will get more specific about fruit and vegetable consumption.

The fear of decreased bone health and subsequent osteoporosis or osteopenia are what lead Sandon—who is not only a dietitian, but who has had RA for 20 years—to focus on calcium and vitamin D intake for herself and her clients with RA.

What To Advise Patients Regarding Diet

There have been a number of studies that address diet and RA, but there’s no clear-cut “winner” that seems to improve RA symptoms in large numbers of patients.

So, with all the conflicting evidence, what’s the best thing to advise RA patients regarding diet? “The day-to-day recommendations for people with RA are to get a balanced diet but focus primarily on a plant-based diet,” says Sandon. “Get plenty of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and get enough protein from lean meat but don’t go overboard. Aim for fish more often than other kinds of protein,” she says. Other foods to include are almonds and other nuts, which provide healthy fats.

These foods will help provide patients with vitamins A, C, and E, which can be important in targeting systemic inflammation. “They help protect the body against inflammatory damage,” says Sandon. “If they’re eating foods high in those nutrients, they’re also getting other compounds in plant foods believed to affect inflammatory pathways.”

If this sounds like the Mediterranean diet that’s discussed frequently nowadays, it’s because it basically is. Sandon calls it a Mediterranean-style diet. “A Mediterranean-style diet is not just helpful for inflammation, but also for heart disease,” she says.

In fact, the review from Dr. Smedslund and coresearchers of various diets and RA found that a Mediterranean eating plan and fasting followed by a vegetarian eating plan seemed to improve pain when compared with an ordinary diet. Still, they also point out that there were no effects on physical function, stiffness, or other important outcomes. Their review also included only a limited number of studies.2

“It is possible that simply changing from an unhealthy to a healthier diet during the study period could explain some of the positive changes in symptoms of RA,” the study authors wrote.

Similar to Sandon, Dr. Zashin tells patients to eat foods that are generally thought to be healthy, such as fruits, vegetables, beans, soy, seafood, healthy grains, red wine, and dark chocolate, and avoid saturated fats and too much red meat.

Gluten-free diets are widely discussed nowadays, but evidence as it relates to RA is not that strong. Although it’s anecdotal evidence, Dr. Zashin observes that eliminating gluten from one’s diet seems to help a number of RA patients who are sensitive to gluten. For a number of others, he observes that the elimination of dairy can help. Using an elimination trial approach with gluten, dairy, beef, or alcohol can be helpful for certain patients if they are willing to give it a try, he says. Still, he realizes that every patient is different and this doesn’t provide blanket recommendations for everyone with RA.

Dr. Zashin’s experience with gluten and RA patients is similar to what Sandon has seen. “It’s possible that some patients will have gluten intolerance, in which case removing those foods would be beneficial, but it’s probably not the case for everyone who has rheumatoid arthritis.”

Dr. Zashin also talks of the value of omega-3 supplements and the use of CherryFlex, a fruit supplement he has worked with that contains antioxidants and anthocyanins.

Sandon advocates with patients the use of 2,000 mg daily of omega-3 supplements containing both docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid. These supplements might help RA symptoms and heart disease, as well. A study published last year in the journal Nutrition with 37 RA patients found that intake of omega-3 acids seemed to affect disease activity and have beneficial effects on RA by decreasing inflammation.4

Omega-3 supplements may also enable someone with RA to use fewer antiinflammatory medications. However, Sandon will caution patients that higher-than-average doses of omega-3 supplements can cause belching, body odor, and blood thinning—the latter of which could be a concern because other RA medications are already thinning the blood.

As someone living with RA herself, Sandon uses a fish oil capsule, calcium, and vitamin D supplements for better bone health, and folate to counteract methotrexate effects.

Taking the Next Steps to Ensure a Healthy Diet

Sandon encourages rheumatologists to refer their patients to registered dietitians. However, in her 20 years as an RA patient, she has rarely heard her physicians discuss this option. Dr. Crilly agrees. “Diet is probably something clinicians don’t take much interest in. It can be a struggle for patients to get a straight answer about diet because of the lack of research,” he says.

Still, a dietitian can not only help a patient focus on healthier eating, he or she can also make sure the patient does not follow a program that is too restrictive, says Dr. Smedslund.

In addition, the Arthritis Foundation has various articles and resources on its website (www.arthritis.org) that discuss diet and arthritis.

Still, all of the emphasis on diet doesn’t mean one should ignore medications. A balanced approach is best, says Sandon. “You need medical treatment to help control symptoms and pain and help the disease from progressing, but you also need to maintain the body through physical activity and diet. When you pair all three elements, I think you get a better outcome,” she says.

Although it may be difficult to pinpoint via clinical studies, further research into diet and RA should ideally try to determine which foods can affect or improve RA symptoms, says Dr. Zashin. RA patients may one day benefit from research tracking diet and arthritis in general, or diet and autoimmune disease.

Vanessa Caceres is a freelance medical writer in Bradenton, Florida.

References

- Renov VI, Arkfeld D, Panush RS. Complementary and alternative medicine for RA. Arthritis Self-Management. July/August 2012:30-33.

- Smedslund G, Byfuglien MG, Olsen SU, Hagen KB. Effectiveness and safety of dietary interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Diet Assn. 2010;110:727-735.

- Crilly MA, McNeill, G. Arterial dysfunction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the consumption of daily fruits and daily vegetables. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:345-352.

- Hayashi H, Satoi K, Sato-Mito N, et al. Nutritional status in relation to adipokines and oxidative stress is associated with disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition. 2012;28:1109-1114.