Few issues in medicine cause as much worry and angst among physicians as the fear of being sued. The concern about medical malpractice litigation is one the leading causes of career dissatisfaction among physicians.1 Remarkably, little is known about why various subspecialties become involved in litigation, and a PubMed search reveals no articles written specifically on the topic of rheumatology lawsuits.

I have a unique perspective. As a risk manager at Colorado Physician Insurance Company (COPIC), I’ve had an insider’s opportunity to analyze and prevent lawsuits. As a board-certified rheumatologist, I have a particular interest in our subspecialty. I reviewed the claims against all rheumatologists that COPIC has insured during the last seven years, and I believe you will find this analysis revealing.

Malpractice Crisis?

Many believe that there is a malpractice crisis in the United States. According to the American Medical Association (AMA), there are only eight states where there is not a crisis malpractice situation. This means there is access to insurance for all specialties and a stable rate environment. Malpractice premium rates vary greatly from state to state, and there are no specific studies on rheumatology premiums. However, rheumatology rates are based on Internal Medicine (IM) physician premiums. In the 2006 survey, IM premiums varied from yearly rates around $3,000 in Nebraska to a high of almost $75,000 in Dade County, Fla.2 The variation is caused by the presence or absence of malpractice caps, state-funded supplemental funds, juries willing to make large awards, high administrative costs, and legal fees.

Malpractice lawsuits are typically filed under conventional tort law. This means that physicians need to be proven negligent to a reasonable degree of medical certainty (greater than 50%). There were few medical malpractice lawsuits prior to the 1970s. In fact, doctors were often covered under their own personal insurance. Not anymore. Litigation has forced physicians to carry malpractice insurance. To win their cases, plaintiffs need to prove: 1) the doctor had the duty to provide care; 2) the physician was negligent and delivered medical care below the standard of care; 3) the patient suffered an injury that was caused by the negligence claimed; and 4) the negligence lead to damages. Jury trials typically revolve around issues two and three.

Here’s the bad news: The risk of getting involved in a malpractice claim approaches 65% over the course of your career.3 Here’s the good news: There is a very small chance that you will end up in court in a lengthy, expensive jury trial. In the course of a given year, only about 40 of the 6,000 physicians that COPIC insures go to trial, and these cases tend to be in more highly sued specialties, such as obstetrics and neurosurgery. Overall, doctors win 80% of their cases when they go to court.

There is a strong disincentive to going to trial for both sides. Costs are high for plaintiffs to try a case – $200,000 to $300,000 in complex cases. Stress and risk of a loss are always a disincentive for the physician. Keep in mind that some insurance companies have a “consent-to-settle” clause in their contracts. This means your carrier may not need your approval to settle your legal case. You should know whether your carrier has such an “against-your-will” clause in your agreement.

Actions that Lower Malpractice Risk

- Building good doctor-patient relationships;

- Being alert in high-risk situations (cardiovascular, neurological, infectious disease);

- Keeping good documentation;

- Obtaining written and verbal informed consent; and

- Paying attention to drug toxicities.

Heads, Hearts, and Bugs

Let’s look at IM issues. The majority of rheumatologists are board certified in IM and, as such, can be held to the standard of care for IM physicians. As practitioners of a specialty that deals with the whole person, rheumatologists often find themselves on the front line, seeing rheumatic patients with chest pain, neurological symptoms, or infections – just as internists do.

The IM experience can be looked at in two ways. One approach is to look at error types. COPIC data suggest that 60% of IM lawsuits arise from failure to diagnose illnesses, 20% from improper care of a known illness, 10% medication errors, and 10% improper procedures. The other way to analyze these findings is to look at the largest category, the failure-to-diagnose group. Here, I find that lawsuits cluster around chest pain (missed pulmonary emboli and myocardial infarctions), neurological problems (missed cerebral vascular accidents and meningitis), underappreciated or missed infections, and failure to diagnose cancer. The mnemonic device I preach is this: Beware of heads, hearts, and bugs. That’s what will get you sued.

For Rheumatology, Medication Issues Are Key

Rheumatology data have some similarities but also some significant differences from those in IM. COPIC malpractice insurance covers about 80% of the private practitioners in Colorado. Between 1999-2005 we covered between 35 and 40 rheumatologists per year. The rheumatology claim rate averaged 5.64 claims per 100 doctor-years. The IM claim rate in comparable years is similar, at 6.26 claims per 100 doctor-years. In rheumatology, 40% of claims were for medicine side effects, including infections on TNF inhibitors and several relating to steroid complications (injection atrophy, avascular necrosis, osteoporosis, and psychosis). The other 60% were for failure to diagnose medical problems or complications of known medical conditions. Prominent were systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) complications with either clotting events, cardiovascular, or neurological issues. There was also a recent settlement (on behalf of an emergency room physician, not a rheumatologist) in a case of temporal arteritis and associated blindness with normal sedimentation rates – rare according to the literature.4

Suits for procedure side effects were rare, as opposed to IM – not a surprise in a quintessential cognitive specialty such as ours. There were also no claims involving pure IM care in nonrheumatic patients or failure to diagnose cancer, suggesting that we are doing less primary care than we have done in the past. What was most striking was the high rate of medication issues that led to legal action among our physicians.

How to Avoid Lawsuits

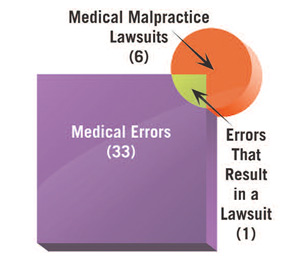

The classic paper on malpractice by Brennan and colleagues stated that only one of six lawsuits has a medical error at its core.5 (See Figure 1) If not for medical errors, then why are physicians sued? Research suggests that reasons for suits include patient dissatisfaction with the physician’s communication skills, trying to obtain more information about their care, concern about a cover-up, and desire for remuneration.6

The first and foremost risk-management tool is a good doctor–patient relationship.7 If patients like you and they feel you were negligent, they consider it a mistake. Everyone makes mistakes. Doctors are forgiven. If they don’t like you and they feel you’re negligent, then they consider it malpractice.8 We all know of physicians who deliver poor care, yet their patients never sue because of their positive feelings toward the doctors. One needs to be alert when caring for high-risk patients (either angry or sick) – especially those who have chest, neurological, or infectious symptoms (heads, hearts, and bugs).

SLE has a striking prominence in terms of the number of cases with unusual complications. The key here is documenting well in high-risk SLE patients – those with cardiovascular, neurological, or infectious symptoms. We need also to be aware of the unusual complications that these patients can develop. Finally, given our high rate of medicine complications, thorough informed consents are vital. This would apply to steroids, leflunomide, cytotoxic drugs, and the new biologic agents. This can be a verbal consent and even a written consent in some cases. COPIC has been using a written steroid consent form for more than a decade and I suggest using it. (Download the form under the “Download Issues” tab.)

The threat of litigation is part of a modern-day physician’s existence. You can diminish your risk through awareness of why other rheumatologists have been sued. The practical behaviors I outlined above will decrease your risk of being involved in a malpractice lawsuit. Beware of heads, hearts, and bugs. Warn patients of drug toxicities and document that discussion. Most importantly, connect with your patients.

Dr. Boyle is assistant professor of medicine at Denver Health Medical Center/University of Colorado Health Sciences Center (UCHSC). He received his MD from Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia and completed an internship at San Francisco General Hospital, a residency at the University of Illinois in Chicago, and a fellowship at UCHSC. After almost 20 years in private practice, he became an emergency room–attending physician at Rose Medical Center in Denver. In 2002, he took his current position.

Dr. Boyle’s primary interest is in doctor–patient communication. He has worked with the Foundations of Medicine program to teach medical students effective and empathetic communication and is a national speaker on issues such as communication and dealing with difficult patients. He has also worked with COPIC on its physician education program.

References

- Skolnik NS, Smith DR, Diamond J. Professional satisfaction and dissatisfaction of family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1993;37(3):257-263.

- Medical Liability Monitor. 2006;31(10).

- Dodge AM, Fitzer SF. When Good Doctors Get Sued: A Guide for Defendant Physicians Involved in Malpractice Lawsuits. BookPartners, Inc.; 2001.

- Salvarani C, Hunder GG. Giant cell arteritis with low erythrocyte sedimentation rate: frequency of occurrence in a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(2):140-145.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Medical malpractice. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(3):283-292.

- Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Githens PB, et al. Factors that prompted families to file medical malpractice claims following perinatal injuries. JAMA. 1992;267(10):1359-1363.

- Levinson W, Roter DL, et al. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553-559.

- DuClos CW, Eichler M, Taylor L, et al. Patient perspectives of patient-provider communication after adverse events. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(6):479-486.