Dr. Seo

To be frank, this has been a dumpster fire of a year. I’m sure I could have found a more elegant turn of phrase to express this thought, but why bother? You were there. You know.

Instead, in a feat of multitasking, I held my toothbrush in my right hand and a kettle in my left, trying not to give myself a third-degree burn while I ran between the kitchen and the bathroom, simultaneously taming my cowlicks. Coffee in hand, I started to button yesterday’s shirt while I was connecting to our patient portal. I then grabbed a pillow from the couch to use as a lap desk, put my Dell on top, looked directly into the camera, smiled, and gave a hearty “Good morning!” to my first patient.

Tragedy, Writ Small

This has been a year of adjustments for all of us. I’ve taken to keeping an extra shaving kit in my desk at work, because I no longer reliably remember to shave before I leave the house, and the scruffy look isn’t always endearing on Zoom calls. I’ve also stopped whistling. Ever since I was a college student, I’ve whistled while I walk, partly to keep awake, partly to lift my spirits. No longer. I’ve decided that even my most blasé colleagues likely wouldn’t appreciate having a high-velocity stream of air coming at them from my mouth.

I know these are small inconveniences compared to what many of you have endured. As an introvert, I have been preparing for a pandemic for my entire life. I actually don’t mind going several days without seeing someone. A video chat, a few emails, and I’m good. Many of you have endured large financial and social changes that are orders of magnitude more disruptive. I am particularly awed by my colleagues with school-aged children, who are working from home with toddlers in tow.

To be frank, this has been a dumpster fire of a year. I’m sure I could have found a more elegant turn of phrase to express this thought, but why bother? You were there. You know.

It started with the fires that have engulfed the Western U.S. with such ferocity that their smoke has been seen as far east as Upstate New York and Washington, D.C.1 An entire generation of children in California is growing up thinking of smoky as a weather condition, like cloudy or sunny. Then came the protests against racial injustice, which have engulfed the nation in a different kind of flame. Of course, any accounting of this miserable year would be incomplete without an enumeration of the giants we have lost: John Lewis. Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Eddie Van Halen. All vanguards in their respective fields, all gone forever. I used to joke that the only thing missing from this year was locusts, until I read that plagues of locusts had invaded the Middle East and Africa earlier this year, leaving somewhere between 5 million and 25 million people at risk of starvation.2

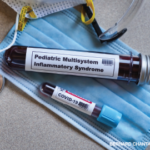

And now we come to SARS-CoV-2. I am not a conspiracist, but it’s hard to look at the virus and not think it was almost perfectly engineered to wreak the maximum amount of havoc. The disease is most contagious when patients are asymptomatic. Once infected, the virus induces endothelial dysfunction that leads to microthrombi that can appear in almost any organ.3 Brain, kidney, heart—nothing is spared. Once over, the infection leaves behind a lingering misery. These patients, described as long haulers in the press, seem reminiscent of patients with chronic Lyme disease and will likely be just as challenging to treat.

By the time you read these words, my best guess is that we will be in the throes of a third wave of COVID-19, complete with lockdowns and overflowing hospitals. I certainly hope I’m wrong; this pandemic has already taken enough from all of us. By April 2020, more American lives had been lost to COVID-19 than to the Vietnam War.4 By September 2020, COVID-19 had taken more than a million lives worldwide.5

When numbers climb to these heights, I think they start to lose their meaning. The Black Lives Matter protests taught us the importance of saying the victims’ names: Rayshard Brooks. Daniel Prude. George Floyd. Breonna Taylor. Eric Garner. Tamir Rice. Philando Castile.6 Even if you don’t support the movement, writ large, it is impossible to hear the stories of these individual lives and not feel compassion for dreams cut short.

With this in mind, I want to tell you the story of Hannah Kim, a 22-year-old college student in Los Angeles.7 In April 2020, her parents decided to move her 85-year-old grandmother, who had dementia, from her nursing home, because of the increasing prevalence of SARS-CoV-2. They quickly realized they were too late; her grandmother was already infected, and after more agonized discussion, they decided to admit her to a local hospital. Again, they were too late. Soon after her grandmother was admitted to the hospital, Hannah found her father slumped over his desk. Just as the ambulance came to collect him, her mother started to have difficulty breathing. Grandmother, father and mother died of COVID-19, one right after the other, leaving Hannah to care for her 17-year-old brother, Joseph.

I can’t remember how I stumbled across her story. I do remember the most heartbreaking part was not reading Hannah’s announcement of her mother’s death. Rather, it was her penultimate announcement, in which she described her excitement over her mother’s improving prognosis, and how she and her brother were keeping each other in line, to smooth their mother’s transition home.