Image Credit: Sebastian Kaulitzki/shutterstock.com

One of your first clinical assignments as a medical student was likely to have been the lung exam. Its key descriptors may still resonate in your mind: inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation. Proudly parading down the hospital corridors, your newly purchased stethoscope snugly tucked inside your lab coat pocket, you carefully place its cold metal diaphragm on your patient’s chest, listening attentively for any of the clues you were just taught that identify pulmonary pathology: rales, rhonchi and rubs, bronchophony, pectoriloquy and egophony—a lexicographer’s vocabulary! Simply knowing the meaning or, better yet, the proper spelling of these words granted you admission to the rarefied world of clinical medicine.

Chest auscultation has always been the vital component of the bedside pulmonary evaluation. We quickly learned that airspaces don’t take kindly to being congested with liquids: blood, mucous, water. Breathlessness and coughing ensue, medical attention is sought, and the cause is addressed.

In contrast, masses of all kinds often seek refuge in the lungs, either by burrowing their way into the pulmonary interstitium or by tucking into the pleural space or one of the chest cavity’s countless lymph nodes. Unlike airspace fluid, their presence is often greeted by a stony silence. No coughs or wheezes, no sounds at all, except perhaps for some egophony, a sound change often so faint that only those individuals possessing supersonic hearing could detect.

Depending on their origin, lung masses often stay silent over the course of months or even years, evading detection, awaiting discovery by serendipity. Years ago, I noticed that Betty, an older woman with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA), was losing weight. Over the course of three months, she had dropped 17 lbs. off her already slight frame.

“I feel great,” was her reply when asked whether she had any of the other constitutional symptoms that make an unintended weight loss worrisome.

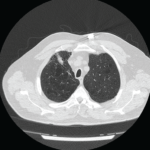

As her asymptomatic weight loss continued, my anxiety climbed. Chest imaging identified a solitary lung nodule, the only abnormal finding in her entire series of tests. There were no clues on the computed tomography studies of her chest that could pinpoint whether this was a benign lesion, perhaps a rheumatoid nodule or something more ominous. With Betty, a lifelong pack-a-day smoker, one had to assume the worst.

Given the lesion’s proximity to some major vascular structures, the sole option was to access it via an open lung biopsy. Splitting through the ribcage of an older patient under general anesthesia is a big deal. However, there was no other choice but to proceed this way.