Now, advanced imaging and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery would have spared Betty the saw.

Fortunately, the lesion turned out to be benign, a solitary rheumatoid nodule. After shedding some 50 lbs., her weight loss mysteriously ceased. Although Betty was grateful that there was no cancer, she never forgave me for putting her through this tumult. To Betty’s many grandchildren who often accompanied her on visits, I became known as the guy who scared her to death!

At least this “false alarm” got her to finally quit smoking.

Pneumatic-Rheumatic

Rheumatologists should not ignore the lungs. This large organ, densely packed with alveoli whose total surface area for gas exchange approaches the size of a football field, often plays more than just a cameo role in many of our diseases.

Lungs may serve as the prime site for autoimmune attack or provide an unwanted refuge for a host of microorganisms. Immunosuppressive drugs, especially the corticosteroids, create a wealth of opportunities for microbial invasion of the airspaces. Then there are the pleural surfaces that, when irritated by infection or autoimmune triggers, emit a telltale leathery friction rub. The distinctively low glucose levels that identify RA-related pleural effusions remains a favorite topic for board exam question writers.

Wizened readers may fondly recall the days when they scoured fresh samples of pleural fluid in search of the rarely spotted yet highly significant lupus erythematosus prep cells.1

When present, the equally rare and mysterious shrinking lung can alert the clinician to the diagnosis of lupus.2

And if the disquieting lung sounds on chest auscultation resemble Velcro strips being pulled apart, they likely portend the incipient scarring of scleroderma or other fibrotic lung diseases.

Of course, some lung diseases raise consideration of select pulmonary–renal syndromes. Often, this combination leads you down the vasculitis pathway, but as I learned, it can also send you in directions that you never considered or even imagined.

A Bleeding Lung

Such was the case with Holly, a patient I have taken care of for the past 15 years. She is a strong woman who has had to cope with the ravages of inflammation since the age of 2 when she developed an erosive, seropositive polyarthritis. Aside from experiencing a number of painful flare-ups of her illness during childhood, she also recalled spending time on the wards of Children’s Hospital in Boston for bouts of breathlessness that were thought to be due to pneumonia. Although always a bit short of breath playing sports, she kept pace with all other activities and went on to a successful career as a development officer at a major charitable institution.

When present, the equally rare & mysterious shrinking lung can alert the clinician to the diagnosis of lupus.

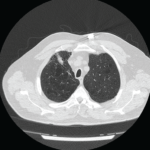

Holly was never one to complain about her arthritis or her slowly declining lung function, so I grew concerned when on a Thanksgiving weekend a few years ago, she was admitted to our hospital for worsening dyspnea and a cough. Chest imaging demonstrated new lung infiltrates. My first instinct was to suspect infection. After all, her immunosuppressive cocktail consisting of methotrexate, prednisone and a TNF inhibitor drug was a microorganism’s delight.