Image Credit: Sebastian Kaulitzki/shutterstock.com

One of your first clinical assignments as a medical student was likely to have been the lung exam. Its key descriptors may still resonate in your mind: inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation. Proudly parading down the hospital corridors, your newly purchased stethoscope snugly tucked inside your lab coat pocket, you carefully place its cold metal diaphragm on your patient’s chest, listening attentively for any of the clues you were just taught that identify pulmonary pathology: rales, rhonchi and rubs, bronchophony, pectoriloquy and egophony—a lexicographer’s vocabulary! Simply knowing the meaning or, better yet, the proper spelling of these words granted you admission to the rarefied world of clinical medicine.

Chest auscultation has always been the vital component of the bedside pulmonary evaluation. We quickly learned that airspaces don’t take kindly to being congested with liquids: blood, mucous, water. Breathlessness and coughing ensue, medical attention is sought, and the cause is addressed.

In contrast, masses of all kinds often seek refuge in the lungs, either by burrowing their way into the pulmonary interstitium or by tucking into the pleural space or one of the chest cavity’s countless lymph nodes. Unlike airspace fluid, their presence is often greeted by a stony silence. No coughs or wheezes, no sounds at all, except perhaps for some egophony, a sound change often so faint that only those individuals possessing supersonic hearing could detect.

Depending on their origin, lung masses often stay silent over the course of months or even years, evading detection, awaiting discovery by serendipity. Years ago, I noticed that Betty, an older woman with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA), was losing weight. Over the course of three months, she had dropped 17 lbs. off her already slight frame.

“I feel great,” was her reply when asked whether she had any of the other constitutional symptoms that make an unintended weight loss worrisome.

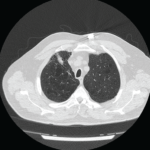

As her asymptomatic weight loss continued, my anxiety climbed. Chest imaging identified a solitary lung nodule, the only abnormal finding in her entire series of tests. There were no clues on the computed tomography studies of her chest that could pinpoint whether this was a benign lesion, perhaps a rheumatoid nodule or something more ominous. With Betty, a lifelong pack-a-day smoker, one had to assume the worst.

Given the lesion’s proximity to some major vascular structures, the sole option was to access it via an open lung biopsy. Splitting through the ribcage of an older patient under general anesthesia is a big deal. However, there was no other choice but to proceed this way.

Now, advanced imaging and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery would have spared Betty the saw.

Fortunately, the lesion turned out to be benign, a solitary rheumatoid nodule. After shedding some 50 lbs., her weight loss mysteriously ceased. Although Betty was grateful that there was no cancer, she never forgave me for putting her through this tumult. To Betty’s many grandchildren who often accompanied her on visits, I became known as the guy who scared her to death!

At least this “false alarm” got her to finally quit smoking.

Pneumatic-Rheumatic

Rheumatologists should not ignore the lungs. This large organ, densely packed with alveoli whose total surface area for gas exchange approaches the size of a football field, often plays more than just a cameo role in many of our diseases.

Lungs may serve as the prime site for autoimmune attack or provide an unwanted refuge for a host of microorganisms. Immunosuppressive drugs, especially the corticosteroids, create a wealth of opportunities for microbial invasion of the airspaces. Then there are the pleural surfaces that, when irritated by infection or autoimmune triggers, emit a telltale leathery friction rub. The distinctively low glucose levels that identify RA-related pleural effusions remains a favorite topic for board exam question writers.

Wizened readers may fondly recall the days when they scoured fresh samples of pleural fluid in search of the rarely spotted yet highly significant lupus erythematosus prep cells.1

When present, the equally rare and mysterious shrinking lung can alert the clinician to the diagnosis of lupus.2

And if the disquieting lung sounds on chest auscultation resemble Velcro strips being pulled apart, they likely portend the incipient scarring of scleroderma or other fibrotic lung diseases.

Of course, some lung diseases raise consideration of select pulmonary–renal syndromes. Often, this combination leads you down the vasculitis pathway, but as I learned, it can also send you in directions that you never considered or even imagined.

A Bleeding Lung

Such was the case with Holly, a patient I have taken care of for the past 15 years. She is a strong woman who has had to cope with the ravages of inflammation since the age of 2 when she developed an erosive, seropositive polyarthritis. Aside from experiencing a number of painful flare-ups of her illness during childhood, she also recalled spending time on the wards of Children’s Hospital in Boston for bouts of breathlessness that were thought to be due to pneumonia. Although always a bit short of breath playing sports, she kept pace with all other activities and went on to a successful career as a development officer at a major charitable institution.

When present, the equally rare & mysterious shrinking lung can alert the clinician to the diagnosis of lupus.

Holly was never one to complain about her arthritis or her slowly declining lung function, so I grew concerned when on a Thanksgiving weekend a few years ago, she was admitted to our hospital for worsening dyspnea and a cough. Chest imaging demonstrated new lung infiltrates. My first instinct was to suspect infection. After all, her immunosuppressive cocktail consisting of methotrexate, prednisone and a TNF inhibitor drug was a microorganism’s delight.

Yet her picture didn’t fit. She lacked a fever. Her white cell counts looked fine, but her red cell count had plummeted from its normal level just a few weeks earlier. Her renal function had deteriorated, as evidenced by a rising serum creatinine and a urinalysis that demonstrated proteinuria and red cell casts. This was not an infection, nor was this due to RA.

Maybe it was vasculitis? Certainly her lung findings were highly suggestive of pulmonary hemorrhage. Days later, with the arrival of a positive antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test result, it was assumed that she was suffering from a systemic vasculitis affecting her lungs and kidneys.

Besides being one of the most critical medical diagnoses, pulmonary hemorrhage had an especially frightening impact on Holly. Not only had her baby sister died of a mysterious lung disease 30 years earlier at age 4, but her older sister had succumbed to respiratory failure a year prior to this admission. And her late sister’s 12-year-old daughter was currently being treated with immunosuppressive therapies for her own progressively worsening lung disease.

A Chance Mutation

Around the time of Holly’s admission, a similar story was being played out a few thousand miles away in San Francisco. Anthony Shum, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) heard of a woman admitted to the emergency department at UCSF with pulmonary hemorrhage (see “A New Syndrome of Autoimmunity,” The Rheumatologist, June 2015).

After visiting the patient’s mother at her bedside, he learned that a distant cousin had a 2-and-a-half-year-old daughter under treatment for pulmonary hemorrhage at a nearby hospital. The mother did not hear about the sickness directly from family members; instead, she heard about it via mutual Facebook friends. Welcome to modern life! Some careful sleuthing uncovered another distant relative with similar symptoms. Reaching out to colleagues at the Texas Medical Center in Houston, they identified a group of 20 affected individuals in five unrelated families who appeared to have a Mendelian syndrome of autoimmunity characterized by high-titer autoantibodies, including ANA, RF and ANCA, an inflammatory arthritis resembling RA, pulmonary hemorrhage or interstitial lung disease and in select patients, features of autoimmune renal disease.4

Using whole exome sequencing techniques, the investigators identified four unique deleterious variants in the ubiquitously expressed coat protein gene, COPA, a resident chaperone in the endoplasmic reticulum. These COPA variants impaired binding to proteins targeted for retrograde transport from the Golgi apparatus to the endoplasmic reticulum.

How might these mutations link mechanistically with autoimmune disease? Faulty protein trafficking by mutant COPA resulted in cellular stress and upregulation of cytokines that triggered a Th17 response. The investigators proposed that such an impairment in cellular trafficking may cause these misfolded proteins to be mistakenly released and, due to their cryptic nature, trigger an autoimmune response.

Although my patient and all of her affected relatives were female, family pedigree analysis of the entire cohort suggested instead a pattern of autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance. Thus, lacking any clues in the family history, might we fail to identify similar patients who are already under our care?

CCP & the Lungs

Although RF was observed in the blood samples of nearly half of the patients studied, the absence of CCP antibody is one clue that distinguishes this form of symmetric inflammatory polyarthritis from RA. The concept that CCP antibodies may originate in the lungs has become one of the hottest topics in RA research.

The story of RA originating in the lungs began decades earlier when a seminal study of Welsh coal miners led by a pulmonologist, Anthony Caplan, MD, identified a syndrome characterized by large, mostly peripheral pulmonary nodules, interstitial fibrosis and the presence of RF. Although many of these miners had arthritis, others developed RA years later, suggesting that the lungs might serve as an incubator for this disease.5

Fast forward about a half a century to when the concept of pre-clinical RA—a stage when individuals show heightened levels of citrullinated antibodies yet lack clinical arthritis—emerged.6 Instead of inhaling silica dust as coal miners did, some cigarette smoking patients were found to generate high levels of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA), thus raising their risk for developing RA (see “Air Pollution: Is There an Association with Rheumatic Disease?” The Rheumatologist, December 2015).

Perhaps we ought to view the lungs as another mucosal surface, in addition to the oral cavity and the gut, that is capable of inducing immune dysregulation in RA. If so, could bronchiectasis, with its predilection for chronic bacterial infection and the development of RF and ACPA, serve as an incubator for the pathogenesis of RA?

A British study of patients with bronchiectasis, some of whom also had RA, observed that those without arthritis often had raised ACPA response, which were not citrulline specific; however, in patients with bronchiectasis who later developed RA, citrulline specificity became a hallmark feature of their breakdown in immune tolerance.7

The data supporting a role for the lungs in the pathogenesis of RA have moved beyond antibody production. A study from Colorado compared the spirometry and lung CT imaging findings in a sample of patients with confirmed RA of less than one year’s duration to a group of ACPA-positive individuals lacking clinical RA. Investigators found similar findings of chronic lung inflammation in both groups.8

Taking these data one step further, using mass-spectrometry-based proteomics, a Swedish group studied bronchial and synovial biopsy specimens from a small group of patients with RA and found identical citrullinated peptides present in both tissues, providing further support for a link between lungs and joints in RA.9

This all reminds me of another patient I met many years ago who drove down from the woods of northern New Hampshire to be evaluated for what his country doctor called lung arthritis. Upon hearing the term, I chuckled and carefully explained how his doctor was clearly mistaken and confused about RA. Now I realize that I was the one who was confused!

Simon M. Helfgott, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Simon M. Helfgott, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Helfgott SM, Kratz A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital: Case 19-2001—A 50-year-old man with fever and joint pain. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jun 21;344(25):1929–1935.

- Hoffbrand BI, Beck ER. ‘Unexplained’ dyspnoea and shrinking lungs in systemic lupus erythematosus. Br Med J. 1965 May 15;1(5445):1273–1277.

- Pullen LC. A new syndrome of autoimmunity: COPA mutation implicated in lung disease & arthritis. The Rheumatologist. 2015 Jun; 9(6):53–54.

- Watkin LB, Jessen B, Wiszniewski W, et al. COPA mutations impair ER-Golgi transport and cause hereditary autoimmune-mediated lung disease and arthritis. Nat Genet. 2015 Apr 20;47(6):654–660.

- Miall WE, Caplan A, Cochrane AL, et al. An epidemiological study of rheumatoid arthritis associated with characteristic chest X-ray appearances in coal workers. Br Med J. 1953 Dec 5;2(4848):1231–1236.

- Klareskog L, Stolt P, Lundberg K, et al. A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: Smoking may trigger HLA–DR (shared epitope)–restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:38–46.

- Quirke A-M, Perry E, Cartwright A, et al. Bronchiectasis is a model for chronic bacterial infection inducing autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2015;67(9):2335–2342.

- Demoruelle MK, Weisman MH, Simonian PL, et al. Brief report: Airways abnormalities and rheumatoid arthritis-related autoantibodies in subjects without arthritis: Early injury or initiating site of autoimmunity? Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Jun;64(6):1756–1761.

- Ytterberg AJ, Joshua V, Reynisdottir G, et al. Shared immunological targets in the lungs and joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Identification and validation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Sep;74:1772–1777.