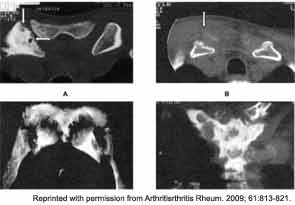

Osteoarticular involvement is especially common in the anterior chest wall, axial skeleton, and large joints such as the wrists, knees, hips, and ankles. The clavicles, sternum, and sterno-clavicular joints are often involved as well (see Figure 5). Spondylodiscitis and unilateral sacroiliitis may be seen on imaging of the axial skeleton.

A major diagnostic dilemma often occurs because the early bone lesions of SAPHO are indistinguishable from those seen in cases of infectious osteomyelitis. In addition, the inflammatory synovial fluid and the destructive lesions seen on imaging require the clinician to seriously consider a septic arthritis and/or osteomyelitis in the differential diagnosis. With time, there may be neutrophilic infiltration with pseudoabscess formation. Ultimately, the bony trabeculae become sclerotic and enlarged. The finding of a “culture negative osteomyelitis” should prompt the rheumatologist to consider the diagnosis of SAPHO.

A series of 71 patients has been described by Colina et al.1 Forty-eight of the 71 patients (68%) were female. Eighty percent had skin disease. The mean age of onset was 38.5 years, but the mean age of diagnosis was 45.5 years. Seventy percent of patients had anterior chest wall involvement, 24% described inflammatory back pain, and only 11% had a peripheral joint synovitis. Fifty-six percent had some form of skin involvement, most commonly PPP.

Markers of inflammation were uncommonly elevated. Only 21% of patients had an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and only 17% demonstrated elevated C-reactive protein. In this series, only 4% of patients were human leukocyte antigen B-27 antigen positive.

Examining Causes

The pathophysiology of SAPHO remains obscure. Many investigators have speculated that there is a bacterial cause for this condition. For example, in one German study, 14 of 21 (67%) needle biopsy specimens of osteitis lesions were culture positive for P. acnes. These 14 patients were combined with 16 other patients who did not have bone cultures performed. All were treated with azithromycin for 16 weeks, chosen because it is concentrated in phagocytic cells and because macrolide antibiotics may have antiinflammatory activity. After 16 weeks of therapy, improvement was noted in the skin, osteitis, and MRI scores. However, when azithromycin treatment was withdrawn after 28 weeks of therapy, the previously noted improvement had regressed.