SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) is an obscure condition that rheumatologists are likely to see. Many rheumatologists may not be familiar with SAPHO. For example, a major rheumatology textbook devotes only three paragraphs to its discussion, and a popular online textbook devotes only 41 lines. However, over a period of one year, the following three patients came under my care. My experience with the first two patients helped me to recognize the diagnosis in the third patient.

Patient 1

A 17-year-old male presented with pain in the thoracic spine and right medial clavicle and skin lesions on his palms and soles, previously diagnosed as pustular psoriasis. A biopsy of the sternum, performed by another physician who was concerned about infection, demonstrated a chronic osteomyelitis without granuloma formation. All microbial culture studies were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine showed increased uptake at the T7 vertebra (see Figure 1). A biopsy of this bone showed marrow fibrosis with plasma cells present and rare lymphocytes. The microbial cultures were sterile. Treatment with oral and subsequently parenteral bisphosphonates and etanercept were all ineffective. He was then treated with infliximab for several months with considerable symptomatic relief and resolution of the MRI abnormality previously seen at T7 (see Figure 2).

Over time, despite progressive increases in the dose of infliximab, he continued to complain of significant pain. He was then treated with golimumab 50 mg monthly with some improvement. Phototherapy was prescribed for his skin lesions. Although the skin lesions improved, after eight months, the back pain worsened. The patient was switched to adalimumab 40 mg every other week. He continues to require narcotic analgesics for pain relief.

Patient 2

A 59-year-old woman developed severe pain in the thoracic spine and shoulder. A radiograph of the thoracic spine demonstrated a suspicious lesion at the T7 level. Biopsy of the lesion demonstrated nonspecific findings, and microbial cultures were negative. A biopsy of the rash over the palms was consistent with a neutrophilic pustulosis. Treatment was initiated with ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. However, the patient developed disabling anterior chest pain for which treatment with several doses of intravenous pamidronate was temporarily helpful.

A rheumatologist at another medical center recommended treatment with adalimumab. This initially produced considerable relief of her chest pain. However, because of a prior history of malignant melanoma, it was recommended that treatment with anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drugs be discontinued. The patient could not tolerate treatment with colchicine. A course of weekly methotrexate was not helpful and was discontinued after several months. She continues to complain of severe anterior chest pain.

Patient 3

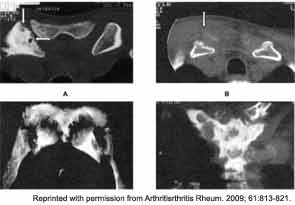

A 70-year-old male developed fever, malaise, and painful swelling in the right wrist and the left sternoclavicular joint. Computed tomography, MRI, and bone scans suggested osteomyelitis in the left sternoclavicular joint (see Figure 3). Radiographs of the right wrist demonstrated intercarpal narrowing (see Figure 4). The patient underwent surgical exploration of the sternoclavicular joint, and the surgeon commented on the appearance of a “thick, cheesy” mass. The histopathology of this lesion demonstrated changes consistent with chronic inflammation and osteomyelitis. Multiple microbial cultures were sterile. The patient was treated with low-dose corticosteroids and a single dose of pamidronate with dramatic improvement in his symptoms.

Discussion

The acronym SAPHO was coined in 1987 to describe a very heterogeneous disorder that typically affects young adults but can also occur in children and the elderly. It is somewhat similar to chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO), which was first described in children in 1972. CRMO and SAPHO are syndromes (i.e., constellations of signs and symptoms in recognizable patterns) rather than well-defined clinicopathological diseases. Whereas CRMO usually involves the long bones in a symmetrical pattern, with little involvement of the jaw and sternum, SAPHO typically affects the anterior chest wall, axial skeleton, and the jaw.

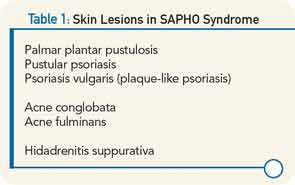

Patients may present with a combination of skin lesions, arthritis, and musculoskeletal pain. As in psoriatic arthritis, the skin lesions may occur before, after, or concurrent with the musculoskeletal manifestations. A variety of skin lesions can occur (see Table 1). Palmar plantar pustulosis (PPP) is localized pustular psorisasis on the palms and soles. More diffuse pustular psoriasis may be seen, or psoriasis vulgaris with the typical plaque-like lesions. Acneform lesions are also common. Acne conglobata presents with comedones, draining sinus tracts, nodules, and abscesses. Acne fulminans is an acute, febrile, ulcerative process, often associated with infection with Propionobacterium acnes. The sweat glands and sebaceous glands are common sites for P. acnes, thought to be potentially pathologic in SAPHO syndrome. Hidadrenitis suppurativa involves the apocrine sweat glands or sebaceous glands, in the axillae, inframammary regions, inner thighs, groins, and buttocks. Chronic abscesses as well as sebaceous and pilonidal cysts are seen.

Osteoarticular involvement is especially common in the anterior chest wall, axial skeleton, and large joints such as the wrists, knees, hips, and ankles. The clavicles, sternum, and sterno-clavicular joints are often involved as well (see Figure 5). Spondylodiscitis and unilateral sacroiliitis may be seen on imaging of the axial skeleton.

A major diagnostic dilemma often occurs because the early bone lesions of SAPHO are indistinguishable from those seen in cases of infectious osteomyelitis. In addition, the inflammatory synovial fluid and the destructive lesions seen on imaging require the clinician to seriously consider a septic arthritis and/or osteomyelitis in the differential diagnosis. With time, there may be neutrophilic infiltration with pseudoabscess formation. Ultimately, the bony trabeculae become sclerotic and enlarged. The finding of a “culture negative osteomyelitis” should prompt the rheumatologist to consider the diagnosis of SAPHO.

A series of 71 patients has been described by Colina et al.1 Forty-eight of the 71 patients (68%) were female. Eighty percent had skin disease. The mean age of onset was 38.5 years, but the mean age of diagnosis was 45.5 years. Seventy percent of patients had anterior chest wall involvement, 24% described inflammatory back pain, and only 11% had a peripheral joint synovitis. Fifty-six percent had some form of skin involvement, most commonly PPP.

Markers of inflammation were uncommonly elevated. Only 21% of patients had an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and only 17% demonstrated elevated C-reactive protein. In this series, only 4% of patients were human leukocyte antigen B-27 antigen positive.

Examining Causes

The pathophysiology of SAPHO remains obscure. Many investigators have speculated that there is a bacterial cause for this condition. For example, in one German study, 14 of 21 (67%) needle biopsy specimens of osteitis lesions were culture positive for P. acnes. These 14 patients were combined with 16 other patients who did not have bone cultures performed. All were treated with azithromycin for 16 weeks, chosen because it is concentrated in phagocytic cells and because macrolide antibiotics may have antiinflammatory activity. After 16 weeks of therapy, improvement was noted in the skin, osteitis, and MRI scores. However, when azithromycin treatment was withdrawn after 28 weeks of therapy, the previously noted improvement had regressed.

The role for genetics has been studied using a murine model of CRMO. There is evidence for a single amino acid mutation in the gene controlling the synthesis of the proline-serine-threonine phosphatase interacting protein 2 on chromosome 18. In Majeed syndrome, a syndrome with similar clinical features to SAPHO (neutrophilic dermatosis and multiple osteitic lesions), there is a mutation of LPIN2, which encodes lipin 2, a protein involved in the apoptosis of polymorphonuclear cells. In PAPA syndrome (pyogenic sterile arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne), there is a mutation on chromosome 15 that affects the CD2-binding protein 1(CD2BP1), which is part of an inflammatory pathway involved in several other autoinflammatory syndromes including familial Mediteranean fever, Muckle-Wells syndrome, neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease, hyper IgD syndrome, and familial cold urticaria. Some investigators speculate that SAPHO syndrome may result from a heightened host response to intestinal bacteria that may be mediated by NOD2/CARD15 synthesis in the inflammasome. NOD2/CARD15 is a “pattern recognition receptor” that recognizes bacterial peptidoglycans and stimulates a response using the innate immune system. Since mutations in NOD2/CARD15 have been identified as a risk factor for the development of Crohn’s disease, is it possible that similar mutations predispose to the development of SAPHO?

P. acnes, the bacteria that derives its name from its production of propionic acid, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of SAPHO. It is widely distributed throughout the body, including the oral cavity, large intestine, conjunctivae, external ear, and skin, especially sebaceous follicles. P. acnes contains numerous genes that generate enzymes that degrade skin and proteins, possibly creating a host of immunogenic antigens in the susceptible host.

Aside from antibiotic therapy as described above, a number of other therapies have been utilized in SAPHO, but evidence supporting each treatment is limited. These include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, methotrexate, and sulfasalazine. There are reports of anti-TNF drugs showing benefit for some patients. Bisphosphonates have an antiosteoclastic effect, and both pamidronate and zoledronic acid have been documented as effective in some case reports. Presently, treatment remains empiric and must be individualized depending upon the severity of symptoms.

In conclusion, SAPHO is a syndrome that can present in many different ways.

The clinician should consider the diagnosis in any patient with “sterile osteomyelitis,” isolated vertebral lesions on imaging studies, severe acne, hidadrenitis suppurativa, or pustular lesions on the palms and soles.

Dr. Brasington is professor and head of the fellowship program at Washington University in St. Louis.

For Further Reading

- Kopterides P, Pikaziz D, Koufos C. Successful treatment of SAPHO syndrome with zoledronic acid. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2970-2973. (This article has a fantastic bone scan image of SAPHO before and after treatment.)

- Rohekar G, Inman RD. Conundrums in nosology: Synvotis, acne, pusulosis, hyperostosis, and Osteitis syndrome and spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 55:665-669.

- Colina M, Govoni M, Orzincolo C, et al. Clinical and radiologic evolution of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis syndrome: A single center study of a cohort of 71 subjects. Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 61:813-821.

- Rozin A. SAPHO syndrome: Is a range of pathogen-associated rheumatic diseases extended? Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:131.

- Assman G, Kueck O, Kirchoff T, et al. Efficacy of antibiotic therapy for SAPHO syndrome is lost after its discontinuation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R140.