CHICAGO—Although rare, when a patient has both primary immune deficiency and autoimmune disease, the combination can lead to life-threatening complications requiring careful, long-term therapy.

In When Immune Deficiency and Autoimmunity Coexist, a session at the 2018 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, M. Eric Gershwin, MD, the Jack and Donald Chia professor of Medicine and chief of Rheumatology, Allergy and Clinical Immunology at the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Sacramento, discussed autoimmunity in a subset of patients with primary immune deficiencies and how to manage these complex conditions.

Rare & Rarer

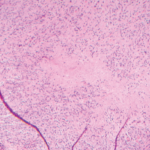

Visual Generation / shutterstock.com

Over the past 50 years, research has revealed a higher incidence of autoantibodies and disease in patients with primary immune deficiency, such as Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.1 In this very rare immune deficiency disease, patients are less able to form blood clots. They are at higher risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and hemolytic anemia. Why do these links exist? Clues may lie in the patient’s genes, as well as how genes are methylated, said Dr. Gershwin.

“There are about 300 [primary immune deficiencies] recognized at this time, and most are caused by genetic abnormalities,” he said. “They involve an inherent deficiency in the innate and/or adaptive components of the body’s immune response.”

To identify patients with primary immune deficiencies, “the things I look for are documentation of repeated sinus infections. Not sinusitis or ‘my head hurts,’ but a sinus image that is repetitively abnormal. Look for repetitive episodes of pneumonias, and persistent infections that just don’t seem to resolve. Those are the major hallmarks,” along with thrush and family primary immune deficiency history, said Dr. Gershwin.

Due to earlier diagnosis and treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, as well as bone marrow transplantation or stem cell transplantation, patients with primary immune deficiency now live longer. Therefore, physicians are detecting complications later in life, including autoantibodies and autoimmune disease, and the primary immune deficiency/autoimmunity combination presents treatment dilemmas for the physician.

‘There’s no correlation between the presence of autoimmune phenomena in a patient with CVID & its severity.’ —Dr. Gershwin

CVID

Common variable immune deficiency (CVID), which affects about one in every 25,000 Caucasians, is one of the most common primary immune deficiencies.2 CVID patients have marked serum reductions in both IgG and IgA, and about half have reduced IgM. Additionally, if IgA and IgM are also low, this combination is a strong sign of CVID.

The disease affects both men and women equally. Often, CVID patients present with upper airway infections, followed by infectious diarrhea and septic arthritis. But they may also have autoimmune diseases: hemolytic anemia, autoimmune thyroid disease, RA and juvenile RA. They may also have enlarged lymph nodes and spleens, as well as bronchiectasis. Patients may have an increased risk of gastric carcinoma, most commonly due to co-infection with H. pylori, said Dr. Gershwin.

Signs of CVID include multiple bacterial or viral infections in a short period of time, poor response to antibiotics, reduced immunoglobulin levels and reduced immune response after vaccinations. But an enormous variation may exist between these patients, said Dr. Gershwin. Cytopenia, bronchiectasis or granuloma, other inflammation or autoimmune diseases are other clues. And in 17.4% of patients, CVID diagnosis comes after the autoimmunity diagnosis.

“There’s no correlation between the presence of autoimmune phenomena in a patient with CVID and its severity,” which may have to do with the genetic basis of the disease, he said. CVID appears both in young children and adults and is a diagnosis of exclusion that is often delayed for years.

In CVID, patients may have a multiplicity of immune cell defects, and each person has different symptoms, complications and disease progression, said Dr. Gershwin. “Perhaps this syndrome, more than almost any other immune deficiency, reflects that it is variable, because it is not one disorder. It represents a multiplicity of disorders all sharing one thing in common: inefficient production of antibodies accompanied by recurrent infections. As we begin to unravel the genetic basis of this disease, individualized, personalized therapy will hopefully improve for these patients.”

Cheaper DNA sequencing has led to the identification of more genetic defects in CVID, but clearly complex, interconnected pathways are at play that are both epigenetic and Mendelian in origin, he said. Although 90% of CVID patients manifest with infections, between 26–30% have autoimmunity.

“So what’s the link? The defect may be closely related to a common susceptibility locus, and it could be that a persistent, opportunistic infection leads by way of molecular mutation that may skew the body toward either a Th1 or Th2 response,” said Dr Gershwin. “There may be incomplete clearance of a pathogen that ultimately leads to some deviation from the immune system or an increased load of apoptosis, leading to an abnormal antigen presentation, increased immune complexes, bystander activation and, ultimately, autoimmunity.”

Multiple familial and environmental factors may influence the immune system in CVID, noted Dr. Gershwin.

“It’s possible that the defect that causes CVID may tilt the immune system toward loss of tolerance and breach of tolerance,” he said. “I can’t give you the reason why someone with primary immune deficiency ends up with autoimmunity. What I can tell you: In patients with CVID, a common variable is abnormal B cell homeostasis.”

Abnormal B cell function leads to loss of tolerance and reduced autoantibodies in these patients, who also, often, have lymphopenia, expansion of CD8 T lymphocytes and reduced thymic output.

Additionally, significant abnormalities exist in a number of T cells in patients with CVID, so much so that some experts believe it is a disease of T cells or that CVID’s B cell defects are a product of T cell deficiency.

“These patients are at much greater risk of defects in adaptive immunity. Interestingly, you cannot have an abnormality in an adaptive response without a corresponding defect in innate immunity. They move together,” said Dr. Gershwin. “Most [primary immune deficiencies] are those of adaptive immunity. The minority are of innate immunity. The reason for that may be that defects of innate immunity may be a fatal disease, and there may even be loss in utero.”

The most common autoimmune diseases associated with CVID are hematologic, although the reason is unclear, he noted. In both men and women with CVID, survival is significantly reduced due to any one of multiple complications, such as lymphoma, hepatitis, structural or functional lung impairment or gastrointestinal disease with or without malabsorption. However, in studies of CVID, autoimmunity was not associated with mortality.