The study of rheumatology (and medicine) in art, history, literature and music is engaging and informative.1-12 In this article, we present some instances when rheumatic and autoimmune diseases in certain individuals may have affected the course of history in Western civilization.

Physicians are usually concerned, appropriately, with the effects of illness on the lives of individuals. However, medical conditions have also profoundly influenced historical events. Here, we explore how rheumatic disease may have affected historical events. Some examples listed in Table 1 (see opposite) are not discussed.

The history of rheumatology is beyond the scope of this article, but some observations are pertinent to our discussion.13-16 Representations of what we now know as osteoarthritis, gout, infectious arthritis and possibly spondyloarthritis exist in antiquity; it was only relatively recently that rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the other rheumatic disorders, particularly the systemic rheumatic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis, were recognized and distinguished from other disorders.5,9,11,14,16 Most experts agree that systemic rheumatic diseases were not generally recognized until about the 18th century.11

Examining the history and evolution of our identification and understanding of rheumatic disease is not only of inherent intellectual interest, but adds perspective to current thinking and practice. When and how rheumatic diseases occurred, or were first recognized, provides insights about possible etiology and pathogenesis. RA is such an example. It was first described in about 1800 CE, coinciding with an increase in sugar consumption in Europe and associated with increased periodontal disease linked to the bacteria P. gingivalis. P. gingivalis infection is recognized as a risk factor for the development of RA in certain individuals due to the bacteria’s ability to citrullinate proteins.5

Saturnine Gout, Lead Intoxication & the Fall of the Roman Empire

The culture of the Western Roman Empire, for most of its 500 years (from the first century BCE to the fifth CE), had a profound and lasting impact on the arts, science and religion. Its power declined considerably in Western Europe until the Germanic barbarian King Odoacer deposed the last Western Roman emperor in 476 CE. Causes for the fall of Rome remain controversial, and historians have posited poor leadership, weakened military power and climate change as possible reasons. But what if an important factor in the demise of the empire was lead poisoning from daily wine and food intake of the aristocracy?

Gout was prevalent in ancient Rome and was described— and satirized—among the wealthy by notable Romans, such as Virgil and Galen.7,17-19 Many Roman Emperors between 15 and 225 CE were known to be heavy consumers of wine and food, and were described as having symptoms potentially consistent with chronic lead intoxication, including severe neuropsychiatric disturbance, neuromuscular dysfunction, gout and abdominal pain.

The principal source of lead poisoning likely stemmed from a grape-based sweetener common in Roman wine. It was produced by boiling grapes in lead-lined vessels, resulting in lead levels in wine ranging from 240–1,000 mg/L. Given that the Romans consumed approximately 1–5 L per person, lead toxicity may have been widespread.20 Worse yet, city pipes, cookware and utensils were also lined with lead. Thus, it is estimated that aristocrats consumed ≥250 mcg/L of lead daily. Consider this: The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set 50 mcg/L as the limit of what’s safe to consume.20

What if … Roman emperors had not been encephalopathic as a consequence of their lead intoxication and saturnine gout? How different might world history have been?

Saturnine Gout, Lead Intoxication, King Herod the Great & Herod Antipas

At least six prominent Herods exist in history, literature, opera and the Bible; they are often conflated, making the interpretation of, and speculation about, their possible medical illnesses challenging.7,8,22

King Herod I (the Great) lived from 73 BCE to 4 BCE in Judea. He was known for his cruelty; his accomplishments included economic and diplomatic successes before the onset of mysterious symptoms and his death due to unknown causes.

The historian Flavius Josephus recorded the life and death of King Herod I, describing symptoms of paranoia, depression, psychosis, high fall risk and extreme forgetfulness. Josephus wrote of Herod that, days before death, his “entrails were … ex-ulcerated.” He described the violence of Herod’s pain in his colon, “aqueous and transparent liquor” about his feet and matter at the bottom of his belly. “His privy member was putrefied and produced worms … when he sat upright. He had a difficulty of breathing, … convulsions … choleric … like a mad man.”23 Symptoms of edema in his lower extremity, dyspnea, abdominal distension and pain, scrotal edema and muscular spasms were described. Lead poisoning and saturnine gout were among an extensive possible differential diagnosis.

Herod the Great’s son, Herod Antipas (21 BCE–39 CE), was tetrarch of Judea and Perea, and the subject of artistic depictions, among which is Salome, the opera by Richard Strauss (Note: derived from an Oscar Wilde play that was inspired by a Gustave Moreau painting), in which the tetrarch ordered the murder of every male under age 2, killed his own sons and executed John the Baptist at the whim of his teenage daughter.7,8

This Herod clearly experienced dementia, hallucinations, paranoia, heavy use of alcohol and drinking the emperor’s wine—a habit perhaps influenced or encouraged by his father’s behaviors—violence, twitches and sterility; different interpretations also show him with falls, chills, shaking, thirst, forgetfulness and sleepiness. We favor the diagnosis of chronic lead intoxication. He had compatible symptoms (e.g., encephalopathy and neuromuscular abnormalities) and consumed excessive quantities of imperial wine, known to be highly contaminated with lead and likely associated with similar symptoms among Roman aristocracy.7,8

What if … King Herod the Great and/or Herod Antipas had not been such prolific consumers of Roman wine? Might the beginnings of early Christianity and the destruction of the Second Temple have been different?

Saturnine Gout, Sir William Pitt & the American Revolution

The gouty attacks of Sir William Pitt the Elder, the British prime minister, have been speculated to be one contributing factor to the American Revolution.18,19 Pitt grew up in a wealthy family that delighted in a diet rich in protein and port; this contributed to numerous episodes of gout in both father and son.

Port wines from lead-lined vats in Portugal have previously been shown to contain toxic amounts of lead, explaining the epidemic of saturnine gout among British aristocracy of that era.17,24 Pitt became a powerful political force and, ultimately, prime minister. He was an outspoken champion of the colonies, believing the American colonies deserved representation with their taxation. Pitt developed an acute episode of gout the night before the vote for the Stamp Act of 1765, stayed home and missed the parliamentary debate; Pitt opposed the act, and historians opine that his influence would have prevailed. The Stamp Act passed and, together with the Tea Act, helped precipitate the American Revolution.19

What if … Pitt, who was influential and sympathetic to the colonies, had not had an acute episode of (saturnine) gout on the eve of that fateful parliamentary debate that led to the passing of the Stamp Act? How different might American and British history have been?

See Table 1 (above) for brief comments about gout affecting King Asa, Charles V and dinosaurs.25-27

Reactive Arthritis & Columbus

The voyages of Christopher Columbus led to colonization of the New World over 500 years ago. However, during this time Columbus suffered from progressive flares of a debilitating arthritis that were associated with febrile and ocular symptoms, which presumably reflected reactive arthritis.28

This was thought to begin during his first voyage, on his return trip to Spain with the Niña and Pinta, in 1493. Columbus wrote that “he had not slept or been able to sleep and hardly had the use of his legs.” During his second voyage in 1494, he reportedly became “gravely ill” with “high fever and a drowsiness, so that he lost his sight, memory and all his other senses.”29 Symptoms caused “general disability” and “errors in navigation.” Columbus remained ill for almost five months thereafter.29-31

On his third voyage, Columbus developed gotte (gout, a term then used to refer to rheumatism or arthritis, generally and non-specifically). Columbus developed lower extremity joint pain, febrile episodes, bilateral eye inflammation, visual changes and pain.29 At age 51, he was “already an aged man,” and by his fourth and final voyage and through his remaining years, he remained largely “paralyzed and bedridden.”32 Columbus’ illness is generally considered to have been reactive arthritis.29

What if … Columbus had not suffered reactive arthritis that affected and limited his voyages of discovery? How different would modern history have been?

See Table 1 for two more examples of spondyloarthritis: The pharaohs, Moses and the biblical exodus, as well as King Sejong and the golden age of Korean culture.33-34

Pain Management, Napoleon & an Epic Defeat at Waterloo

Napoleon, an emperor aspiring to dominate Europe, was invincible until the fateful Battle of Waterloo in 1815.35 It was Napoleon’s military leadership style to awaken early on the mornings of battles and to lead his troops into the fray. Significantly, and unusually, that did not happen at Waterloo. Napoleon rose late in the morning, reportedly spent much of the day napping, off horseback and walking with “difficulty with his legs spread apart,” and did not provide his customary leadership.35,36 Napoleon suffered painful bouts of hemorrhoids.35 It has been speculated this was likely what happened on the eve of the Battle of Waterloo and that Napoleon was administered sedative analgesics—perhaps narcotics—that impaired his ability to direct his army the following day.

Figure 1B. Boris M. Joffe, father in-law of one of the authors, Dr. Panush, in the early 1900s, probably on the streets of St. Petersburg, where he was born. He was a protégé of and assistant to Viktor Chernov, leader and theoretician of the socialistrevolutionary anarchist party of Russia. Chernov was minister of agriculture in Alexander Kerensky’s Russian Provisional Government and chair of the Russian Constituent Assembly, the duly elected government in the country in a plebiscite held following the fall of the tsardom, lasting until they were deposed by Lenin and the Communists.

What if … Napoleon hadn’t (likely) taken excessive pain medication (likely narcotic) for his thrombosed hemorrhoids on the eve of the epic battle at Waterloo, impairing his leadership and presaging his defeat? How might modern European history have differed?

Royal Hemophilia, Possible Hemophilic Arthropathy, Tsarevich Alexei & the Fall of the Romanov Tsardom

In September 1912, the Russian royal family was vacationing at one of its hunting preserves in the Bialowieza Forest, in what is now eastern Poland, with their five children, including Tsarevich Alexei, the long-awaited heir to the Russian throne.37 Alexei had hemophilia, inherited from his mother, Alexandra, of Hessian royalty, granddaughter of Queen Victoria, whose descendants carried the gene.38,39 Alexei fell against an oarlock with an intense pain in his left upper leg and lower abdomen, completely incapacitating him.40 His condition deteriorated, and he was administered last rites.

The tsarina was a foreigner to the country of her husband, Tsar Nicolas II; she was largely isolated, alone and friendless at the court, trusting few except the dissolute and charismatic monk who had captivated her, Grigori Rasputin. In desperation, Alexandra sent a telegram to Rasputin, to which he responded, “God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Do not grieve. The Little One will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much.” The bleeding stopped the next day, and Alexei recovered.

Consequently, Rasputin became the tsarina’s trusted confidant; surely, if he could save her son’s life, he could help her govern Russia while her husband was with his troops at the front during WWI. Russia’s entry into the war and the tsarina’s interim governance of the nation (with Rasputin’s complicity) were disastrous debacles, leading to the fall of the Romanov tsardom.37

Events following Nicolas’ abdication were complex, with provisional governments, including one led by Alexander Kerensky, deposed by Vladimir Lenin and the Communists in the revolution of October 1917.41 (see Figures 1A–1D).

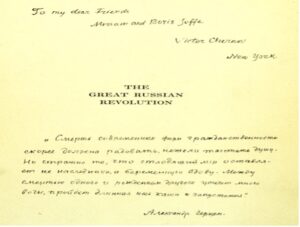

Figure 1D. Inscription from The Great Russian Revolution (1936), given to Miriam and Boris Joffe (in-laws of one of the authors, Dr. Panush) by Viktor Chernov.41 The inscription translates to: “The death of modern forms of civil society should, perhaps, be something to celebrate rather than to burden our souls. But what is frightening is that the old world leaves behind not an heir, but a pregnant widow. From the death of the former to the birth of the new quite some time will pass— fraught with chaos and desolation.” (Attributed to Alexander Herzen, 1812–1870, a Russian socialist ideologue.) (See also Figure 1D PT2 below.)

What if … Tsarevich Alexei did not have a near-fatal episode of hemophilia (possibly with attendant arthropathy) at the royal hunting lodge, leading the tsarina to involve Rasputin in her confounding governance of the country while Nicolas was at the front (“if there had been no Rasputin, there would have been no Lenin” [Alexander Kerensky])? How different might 20th century history have been)?

Possible Giant Cell Arteritis, Hitler & the Rise & Fall of the Third Reich

Adolph Hitler was known to suffer from several medical conditions, possibly including giant cell arteritis (GCA).42 As a child, he suffered pulmonary illness, and he was exposed to toxic substances, including mustard gas during World War I.43 At age 47 he was diagnosed with eczema and dyspepsia.42

In 1941, Hitler experienced fatigue, malaise, dizziness, abdominal pain, left temple pain and tenderness, tinnitus, had a systolic blood pressure of 170 mmHg and “coronary insufficiency,” diagnosed as vascular spasm and colitis.42 On July 22, 1942, he developed severe right-sided headaches and unilateral painless vision changes on the right, considered coronary sclerosis and vascular spasm. He was treated with intravenous glucose, cold compresses and leeches.42,43 From 1942 to 1944, Hitler had more than 13 similar attacks.

In 1943, he had a “swollen” temporal artery, recurrent abdominal pain, distension and jaundice, diagnosed as gastritis. Resting tremor and gait abnormalities were diagnosed as Parkinson’s disease.42 In late 1944, Hitler had weight loss, fever and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 36 mm/hr and 70 mm/2 hr.42 March 1944 brought worsening vision (20/80 acuity) and cloudiness of the vitreous body.43

The differential diagnosis here is broad and should include vasculitis. Could the symptoms of temporal pain, vision changes, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, weight loss, fevers and perhaps certain others have been GCA? Could Hitler’s known amphetamine use have contributed?42 We suspect the answers are “no” and “no,” but the conjecture is not unreasonable. This illustrates the fun of speculating about possible illnesses in historical figures, but also the limitations of the exercise (a comment that generalizes to the entirety of this piece).

What if … Hitler did have giant cell arteritis and could have been treated? How different might that era have been?

Autoimmune Diseases in the White House: Possible Axial Spondyloarthropathy, Autoimmune Polyendocrinopathy Type 2, John F. Kennedy & Presidential Decision Making

John F. Kennedy was our youngest president, 43 years old when he took office. We present him with another president who had autoimmune disease, although his place in history could have been with those having spondyloarthritis (or issues of pain management).

For many years the president’s medical records were secret.44,45 Kennedy was born May 29, 1917. He had a sister with Addison’s disease.46 In 1931, he experienced chronic abdominal symptoms. He also had joint pains, and inflammatory bowel disease was suggested.44,46 In 1934–35, Kennedy had lymphopenia.45 Back pain started in adolescence and progressed in the setting of multiple sports injuries.46,47 He underwent several operations for lumbosacral instability; imaging documented alignment and fusion at L5–S1.47 A clear cause for this was not identified, and he later used crutches.44,47

In 1940, a systolic blood pressure of 80 mmHg was recorded. Kennedy had gastrointestinal symptoms then, and chronic urethritis, for which he took antibiotics.45 He also experienced episodes of syncope and exhaustion; during a trip to England in September 1947, he was diagnosed with adrenal crisis, returned home and was hospitalized in Boston, treated with desoxycorticosterone acetate and cortisone 25.48 It was reported he also suffered from complications of malaria.48

In 1954, Kennedy had his second back operation and was reported as Case 3 in a journal outlining management of adrenal disease in the perioperative period.47,48 Unfortunately, his procedure was complicated by severe wound infections, shock and near death, and he remained hospitalized for several months.44,47 In 1955, he was again hospitalized and started on levothyroxine for treatment of hypothyroidism. Of interest, spinal imaging done in 1957 demonstrated inflammation at the right sacroiliac joint.47 Due to the simultaneous diagnosis of hypoadrenalism and hypothyroidism, Kennedy was considered to have had autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 2.48

In 1961, a list of Kennedy’s medications included hydrocortisone, prednisone, methyltestosterone, fludrocortisone, phenobarbital, paregoric (a hydroalcoholic solution containing opium), diphenoxylate, meperidine, methadone, codeine, amphetamines, chlordiazepoxide, meprobamate, methylphenidate and gamma globulin, a rather formidable menu of medications with the potential to affect cognition.48

It has been speculated that he may have suffered from progressive osteoporosis as a result of chronic steroid use.44 Perhaps Kennedy’s back problems directly contributed to his death; a rigid back brace he wore for uncontrolled symptoms kept him upright after the first gunshot at Dallas, which might not have been fatal by itself.49,50

Some of the notable events of the Kennedy presidency include his affair with Marilyn Monroe, the Cuban missile crisis, the Bay of Pigs invasion, the beginning of the Vietnam war, the Berlin airlift, initiation of space exploration, desegregation and civil rights legislation, and the founding of the Peace Corps.

What if … John F. Kennedy had not been symptomatic from autoimmune adrenal insufficiency and inflammatory spine disease, was not consuming a daunting cocktail of analgetic and other mind-altering medications, and did not need to wear a back brace on that fateful day in Dallas? How different might his presidency and the history of those times have been?

Autoimmune Thyroid Disease, Canine Lupus, George H.W. Bush & a Debacle with the Japanese Prime Minister

In 1991, when he was 66, President George H.W. Bush became breathless while jogging. An electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation. Later that year he announced he had Graves’ disease.51 He was hospitalized multiple times for uncontrolled symptoms. Interestingly, his wife had the same diagnosis two years earlier, and their son would be diagnosed with ulcerative colitis.52 The White House dog, Millie, had canine lupus. All of these conditions are considered autoimmune disorders.53-55

One possible complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism includes flu-like symptoms, such as nausea, fevers and vomiting. It has been speculated that such an episode may have led to Bush’s vomiting on the Japanese prime minister at a state dinner in January 1992.56 Perhaps the perceived weakness of Bush due to chronic illnesses provided an opportunity for the opposing presidential campaign to exploit Bill Clinton’s image of youth and vitality.52

What if … George H.W. Bush didn’t develop hyperthyroidism or had it sufficiently controlled so as to prevent the embarrassing events of the state dinner with the Japanese prime minister? Might his public image have been sufficiently different that he could have been reelected?

Conclusion

We hope this selective presentation of possible instances of rheumatic diseases and related conditions affecting history has been of interest and offered a different perspective and broader appreciation of the connections between illness and historical events.

Baljeet Rai, MD, is a post-doctoral fellow in the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine.

Baljeet Rai, MD, is a post-doctoral fellow in the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Abhimanyu Amarnani, MD, PhD, is a post-doctoral fellow in the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York City.

Ja-yoon Uni Choe, MD, is a resident in the Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, and Los Angeles County + University of Southern California (LAC+USC) Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Ja-yoon Uni Choe, MD, is a resident in the Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, and Los Angeles County + University of Southern California (LAC+USC) Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Nicole K. Zagelbaum Ward, DO, MPH, was a post-doctoral fellow in the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, and Los Angeles County + University of Southern California (LAC+USC) Medical Center, Los Angeles; she is currently in private practice in Los Angeles.

Nicole K. Zagelbaum Ward, DO, MPH, was a post-doctoral fellow in the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, and Los Angeles County + University of Southern California (LAC+USC) Medical Center, Los Angeles; she is currently in private practice in Los Angeles.

Richard S. Panush, MD, MACP, MACR, is professor emeritus in the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Richard S. Panush, MD, MACP, MACR, is professor emeritus in the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

References

- Panush RB, Caldwell JR, Panush RS. Corot’s ‘gout’ and a ‘gypsy girl.’ JAMA. 1990 Sep 5;264(9):1136–1138.

- Panush RS. Chapter 8. Miscellaneous. In: Panush RS (ed). Year Book of Rheumatology, Arthritis, and Musculoskeletal Disease. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2007. pp 320–321.

- Panush RS. Rheum with a view: A musical interlude; Orchestral harmony, the immune system, and rheumatic disease; and When does the music stop? The Rheumatologist. 2011 Apr 13:5:74–75.

- Panush RS. Rheum with a view: Embark on a humanities journey. The Rheumatologist. 2011 Nov 1;5(11):47–49.

- Panush RS. Rheum with a view. Why did rheumatoid arthritis begin in 1800? The Rheumatologist. 2012 Sep 5:6(9):40–41.

- Kaptein AA, Smyth JM, Panush RS. Wolf—living with SLE in a novel. Clin Rheumatol. 2015 May;34(5):887–890.

- Leatherwood C, Panush RS. Did King Herod suffer from a rheumatic disease? Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Apr:36(4):741–744; and Re: Re: Did King Herod suffer from a rheumatic disease? Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Oct;36(10):2395.

- Woolever G, Downey C. What might have been. AIMplus. 1988 Oct;18;58–60.

- Stolyar L, Matteson E, Panush RS. The antiquity of rheumatic diseases as in Giovanni Morgagni’s 1761 De Sedibus Et Causis Morborum Per Anatomen Indagatis. The Pharos. 2021 Summer;84(3):28–36.

- Panush RS. Occupational & recreational musculoskeletal disorders. Chapter 38, Firestein & Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 11th Edition. Firestein GS, Budd RC, SE Gabriel, et al., eds. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2021.

- Appelboom T, ed. Art, History and Antiquity of Rheumatic Diseases. Brussels: Elsevier; 1987.

- Sandblom P. Creativity and Disease. Philadelphia: George Stickley; 1982.

- Blumberg B. The history of arthritis and rheumatism. Arthritis Rheum. 1960 Oct;3(5):421–422.

- Benedek TG, Rodnan GP. A brief history of the rheumatic diseases. Bull Rheum Dis. 1982;32(6):59–68.

- Smith CD, Cyr M. The history of lupus erythematosus. From Hippocrates to Osler. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1988 Apr;14(1):1–14.

- Matteson EL. Notes on the history of eponymic idiopathic vasculitis: The diseases of Henoch and Schonlein, Wegener, Churg and Strauss, Horton, Takayasu, Behçet, and Kawasaki. Arthritis Care Res. 2000 Aug;13(4):237–245.

- Ball GV. Two epidemics of gout. Bull Hist Med. 1982 Sep-Oct;45(5):401–408.

- Copeman WSC. A Short History of the Gout and the Rheumatic Diseases. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1964.

- Nuki G, Simkin PA. A concise history of gout and hyperuricemia and their treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S1.

- Nriagu JO. Saturnine gout among Roman aristocrats. Did lead poisoning contribute to the fall of the empire? New Engl J Med. 1983 Mar 17;308(11):660–663.

- Delile H., Blichert-Toft J, Goiran JP, et al. Lead in ancient Rome’s city waters. Proc Natl Acad Sciences U S A. 2014 May 6;111(18):6594–6599.

- Grove DI. Re: Did King Herod suffer from a rheumatic disease? Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Oct;36(10):2393.

- Josephus F. Book XVII. Chapter VI. Section 5. The Works of Flavius Josephus, Vol II. Translated by Whiston W. London: Chatto and Windus; 1845.

- Halla JT, Ball GV. Saturnine gout: A review of 42 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1982 Feb;11(3):307–314.

- Rosner R. Gout in the Bible and Talmud. JAMA. 1969 Jan 6;207(1):151–152.

- Ordi J, Alonso PL, de Zulueta J, et al. The severe gout of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. New Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 3;355(5):516–520.

- Rothschild BM, Tanke D, Carpenter K. Tyrannosaurs suffered from gout. Nature. 1997 May 22;387(6631):357.

- Allison DJ. Christopher Columbus: First case of Reiter’s disease in the old world? Lancet. 1980 Dec 13;2(8207):1309.

- Weissmann G. They all laughed at Christopher Columbus. Hosp Pract (Off Ed). 1986 Jan 15;21(1):29–30, 35–7, 41.

- Weissmann G: They all laughed at Christopher Columbus: Tales of medicine and the art of discovery. New York: Times Books; 1987. pp10–23.

- Arnett FC, Merrill C, Albardaner F, Mackowiak PA. A mariner with crippling arthritis and bleeding eyes. Amer J Med Sci. 2006 Sep;332(3):123–130.

- Hoenig LJ. The arthritis of Christopher Columbus. Arch Intern Med.1992 Feb;152(2):274–277.

- Appelboom T, Russell A. Moses: Did he inherit the spondylarthrits of the pharaohs? Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Feb 15;49(1):142–148.

- Lee JH. Did Sejong the Great have ankylosing spondylitis? The oldest documented case of ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021 Feb;24(2):203–206.

- Welling DR, Wolf BG, Dozois RR. Piles of defeat. Napoleon at Waterloo. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988 Apr;31(4):303–305.

- Barral G. La Santa de Napoleon Ier. La Chronique Medicale. 1900;7:39–42.

- Masie RK. Nicholas & Alexandra. New York: Atheneum; 1968.

- McKusick VA. The royal hemophilia. Scientific American. 1965 Aug 1;213:88–95.

- Stevens RF. The history of haemophilia in the royal families of Europe. Br J Haematol. 1999 Apr;105(1):25–32. Erratum in Br J Haematol. 1999 Dec;107(4):905.

- Willbanks OL, Willbanks SE. Femoral neuropathy due to retroperitoneal bleeding. A red herring in medicine complicates anticoagulant therapy and influences the Russian Communist Revolution (Crown Prince Alexis, Rasputin). Am J Surg. 1983 Feb;145(2):193–198.

- Chernov V. The Great Russian Revolution. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 1936.

- Redlich FC. A new medical diagnosis of Adolf Hitler. Giant cell arteritis—temporal arteritis. Arch Intern Med. 1992 Mar 22;153(6):693–697.

- Cogan DG. Life events and visual symptoms of Adolf Hitler (with personal anecdotes). Doc Ophthalmol. 1995;89(1-2):9–13.

- Helfgott SM. John F. Kennedy’s odyssey in search of diagnosis. The Rheumatologist. 2013 Nov 1;7(11):10–11.

- Dallek R. The medical ordeals of JFK. The Atlantic. 22 Dec 2002.

- Macchia D, Lippi D, Bianucci R, Donell S. President John F Kennedy’s medical history: Coeliac disease and autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2. Postgrad Med J. 2020 Sep;96(1139):543–549.

- Pait TG, Dowdy JT. John F. Kennedy’s back problems, failed surgeries, and the story of its effects on his life and death. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017 Sep;27(3)247–255.

- Mandel LR. Endocrine and autoimmune aspects of the health history of John F. Kennedy. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Sep 1;151(5):350–354.

- Lattimer JK. Factors in the death of President Kennedy. JAMA. 1966 Oct 24;198:327–333.

- Lattimer JK. Additional data on the shooting of President Kennedy. JAMA. 1993 Mar 24–31;269(12):1544–1547.

- Okie S. 1991. Bush’s thyroid condition diagnosed as Graves’ disease. The Washington Post. 10 May 1991.

- Page S. How a medical mystery tilted the 1992 election in Bill Clinton’s favor. Politico. 1 April 2019.

- Altman LK. The doctor’s world. Seeking clues to immune diseases at the White House. The New York Times. 28 May 1991.

- Panush RS, Levine M, Reichlin M. Do I need an ANA? Some thoughts about man’s best friend and the transmissibility of lupus. J Rheum. 2000 Feb;27(2):287–291.

- Lahita RG. Autoimmunity in the White House. Personal communication, May 5, 2014.

- Healy B, Littlefield N. Presidential ailments. The Atlantic. January–February 2005.