What a delightful couple: Maria, the highly caffeinated, chain-smoking, raspy voiced lady with severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Vinny, her adoring nephew and personal chauffeur who faithfully accompanied her on every visit.

Each encounter began in much the same way: Maria, a waif of a woman with boundless energy, would tear into my office, plant a kiss on my cheek and proceed to wag a crooked finger, exhorting me to start eating the mouth-watering cannoli that Vinny had brought especially for me from their favorite Italian bakery in Boston’s North End. As I filled my mouth, she would start speaking a mile a minute, first inquiring about my family and which travel destinations I might be heading to. She would then proudly display the latest photos of her many adoring grandnieces and nephews, assiduously reciting their latest academic and athletic accomplishments. We would finally get down to the business at hand—how she was feeling.

Were the drugs helpful? Had she tried tapering off prednisone?

Maria was forever the optimist, having endured the consequences of living with poorly controlled RA. She was always hoping for some pot of gold—that new blockbuster drug that might transform her life.

This visit began in the same buoyant fashion as all the others, but it took an ominous turn after the pastries were consumed. Maria’s speech didn’t sound right; its usual rapid-fire tempo was punctuated by some very slight pauses, as though she needed to slow down and catch her breath. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one to have noticed this change. Vinny confided that he was growing alarmed that his aunt wasn’t keeping up with her activities as she usually did. It was his idea to move up the date of Maria’s scheduled appointment when he caught his aunt napping at the kitchen table.

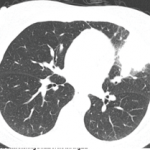

As doctors, we are trained to look and observe. As rheumatologists, we often begin by looking at the hands. Sometimes they recite the patient’s story far more effectively than words. What I saw in Maria’s hands took my breath away. It wasn’t the swollen knuckles or her longstanding boutonnière finger deformities that alarmed me. It was the curious bulbous appearance of her fingertips portending the development of clubbing. Maria thought the odd shape developed literally overnight. Her hands were more painful than usual, which she assumed was just a part of her RA. Although the differential diagnosis of a lifelong smoker developing new clubbing and shortness of breath includes several infectious and cardiorespiratory possibilities, it seemed likely that one dire diagnosis would rise above the rest. This story was not going to have a happy ending.