What a delightful couple: Maria, the highly caffeinated, chain-smoking, raspy voiced lady with severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Vinny, her adoring nephew and personal chauffeur who faithfully accompanied her on every visit.

Each encounter began in much the same way: Maria, a waif of a woman with boundless energy, would tear into my office, plant a kiss on my cheek and proceed to wag a crooked finger, exhorting me to start eating the mouth-watering cannoli that Vinny had brought especially for me from their favorite Italian bakery in Boston’s North End. As I filled my mouth, she would start speaking a mile a minute, first inquiring about my family and which travel destinations I might be heading to. She would then proudly display the latest photos of her many adoring grandnieces and nephews, assiduously reciting their latest academic and athletic accomplishments. We would finally get down to the business at hand—how she was feeling.

Were the drugs helpful? Had she tried tapering off prednisone?

Maria was forever the optimist, having endured the consequences of living with poorly controlled RA. She was always hoping for some pot of gold—that new blockbuster drug that might transform her life.

This visit began in the same buoyant fashion as all the others, but it took an ominous turn after the pastries were consumed. Maria’s speech didn’t sound right; its usual rapid-fire tempo was punctuated by some very slight pauses, as though she needed to slow down and catch her breath. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one to have noticed this change. Vinny confided that he was growing alarmed that his aunt wasn’t keeping up with her activities as she usually did. It was his idea to move up the date of Maria’s scheduled appointment when he caught his aunt napping at the kitchen table.

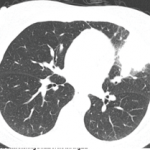

As doctors, we are trained to look and observe. As rheumatologists, we often begin by looking at the hands. Sometimes they recite the patient’s story far more effectively than words. What I saw in Maria’s hands took my breath away. It wasn’t the swollen knuckles or her longstanding boutonnière finger deformities that alarmed me. It was the curious bulbous appearance of her fingertips portending the development of clubbing. Maria thought the odd shape developed literally overnight. Her hands were more painful than usual, which she assumed was just a part of her RA. Although the differential diagnosis of a lifelong smoker developing new clubbing and shortness of breath includes several infectious and cardiorespiratory possibilities, it seemed likely that one dire diagnosis would rise above the rest. This story was not going to have a happy ending.

A short while later, a call from the radiologist confirmed my fears. Maria’s chest X-ray had demonstrated a large, irregular mass in her right upper lobe that was partially collapsing the lung. Maria had lung cancer.

Les Doigts Hippocratiques

Some medical historians consider clubbing to be the oldest sign in medicine. Nearly 2,500 years ago, Hippocrates astutely recognized that digital clubbing was a sinister sign of illness in the chest, vividly describing that, “if you put your ear against the chest you can hear it [pus] seethe inside like sour wine.”1

Although the link between clubbing and lung disease remains undisputed, the underpinnings of this relationship have remained obscure. The first clue came from the work of the prolific French neurologist, Pierre Marie, MD, and the Austrian internist, Eugen von Bamberger, MD, who, working separately, described the degree of bone proliferation and periosteal involvement seen in clubbing, leading Dr. Marie to rename the condition, pulmonary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy.

A second clue arrived 40 years later with the publication of a small series of British patients with clubbing. Several of them were initially thought to have RA, but were found instead to have a pulmonary malignancy without evidence for empyema, tuberculosis or lung abscesses, which had been the most commonly observed findings in patients with clubbing.2

For a while, humoral factors and excessive vagal nerve stimulation (vagotomy helped lessen the hand pain in a few patients) were considered to be the prime mediators of clubbing, but neither of these vague explanations was intellectually satisfying. About 30 years ago, it was proposed that an accumulation of megakaryocyte fragments or platelet aggregates that bypassed the lung capillary network in various cardiac and pulmonary diseases could increase finger vascularity and permeability and promote mesenchymal cell growth to produce periosteal new bone formation and clubbing via the release of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) from the small vessels of the fingertips.3 Subsequent research identified vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as the likely critical cytokine in the pathogenesis of the periostitis in clubbing.4

Another pivotal observation was the identification of a specific genetic mutation of a prostaglandin transporter enzyme in many patients afflicted with the familial form of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, which markedly elevated their levels of circulating prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 is a potent stimulator of VEGF-mediated osteoblast activation and bone formation and its striking concentration in certain individuals with clubbing may obviate their need to have a chest full of “seething pus.”

Clinical experience has taught us that the sign of clubbing is more likely to be the harbinger of a deadlier disease than a lung infection, namely lung cancer. In effect, clubbing became one of the first paraneoplastic signs. With the exception of an earlier report in the French literature published near the end of the 19th century that first described a link between cancer and possible paraneoplastic findings affecting the central nervous system, clubbing opened clinicians’ eyes and minds to the concept that occult malignant disease can leave important clues at distant sites, far removed from the tumor.5 One only needs to know where to look.

It’s All in the Hands

One of the most intellectually satisfying aspects of our specialty is how, just by using our eyes and our minds, we can often spot precious clinical pearls that may instantly define a diagnosis. Although these clues may seem obvious to us, other physicians who rely less on the physical exam and more on advanced technology often overlook these leads. Save for the esoteric labs and the costly imaging, our services come cheap.

Let’s go back to looking at the hands in search of other potentially paraneoplastic findings. Similar to clubbing, the appearance of acanthosis palmaris can herald a lung or gastric malignancy. The palms have a velvety smooth pink appearance, reminding some observers (no doubt, devotees of the whole animal consumption movement) of tripe, that edible offal made from the stomach linings of various large farm animals. Hence, this sign may be better known by its gastronomic appellation, tripe palms.

Other hand features may seem odd or obscure to some but are readily recognized by rheumatologists as potentially pointing to unfavorable diagnoses. For example, the curious swelling syndrome that may erupt in the hands of older men, remitting seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting edema (RS3PE), has been implicated by various authors as signifying a paraneoplastic finding. After all, reports suggest that nearly one-quarter of afflicted individuals develop a malignancy, although given the advanced age of most patients with RS3PE, this may not be as robust an association as it sounds.4

In another disorder, the palmar fasciitis and polyarthritis syndrome that generally affects older women, the deeper tissues of the hands may initially become painfully swollen, only to quickly shrivel and severely contract. The hallmark feature is inflammation of the palmar fascia, which leads to flexion contractures with nodular thickening similar to, but more severe than, those seen with Dupuytren’s contracture.6 These hard, indurated tissues give the appearance of woody hands, another ominous sign that often foreshadows an occult malignancy involving the female reproductive organs, especially the ovaries. In some unfortunate individuals, digital ischemia may evolve to gangrene, heralding an intra-abdominal tumor. This is the paradox of paraneoplasia, in which musculoskeletal manifestations that at first glance suggest a primary rheumatologic diagnosis are actually hinting at the actions of distant cancer cells.

One of the most intellectually satisfying aspects of our specialty is how, just by using our eyes and our minds, we can often spot precious clinical pearls that may instantly define a diagnosis.

Cancer & Autoimmunity: Is there a link?

Of course, no hand exam would be complete without a search for Gottron’s papules, those violaceous lesions with a predilection for the knuckles that identify dermatomyositis and its attendant risk for malignancy. Dermatomyositis can be a challenging disease to manage, especially when it’s refractory to treatment. Is the disease under the spell of an occult malignancy that is driving an aberrant immune response? This tantalizing concept has been raised countless times in the past, but until recently there was little scientific evidence to support it. However, a recent landmark study, albeit in another disease, may shed some light on the link between cancer and autoimmunity.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore took advantage of the clinical observation that a subset of patients with scleroderma who produce autoantibodies to RNA polymerase-1 (RPC1) are highly susceptible to developing cancer.7 They examined tumor tissue and blood samples from 16 scleroderma patients with various types of cancer. Among the eight patients who had anti-RPC1 autoantibodies and coincident cancer, six had genetic mutations—either somatic mutations or loss of heterozygosity (only one copy of an allele) in POLR3A (polymerase III polypeptide A, the gene encoding RPC1). The other eight patients had autoantibodies to the two other antigens commonly associated with scleroderma, either topoisomerase 1 (anti-TOP1) or centromere protein B (anti-CENPB), and all developed delayed cancer. Interestingly, all the anti-RPC1 antibodies recognized both wild-type and mutated RPC1, indicating that the humoral immune response did not directly target the area of the mutation or discriminate between mutant and wild-type versions of RPC1. But some patients with scleroderma who possessed defined POLR3A mutations had T cells that reacted to RPC1 protein fragments produced from the mutated gene. The reactivity was specific to the patient and peptide, but the frequencies of these T cells were comparable to those observed in other autoimmune diseases. Given that POLR3A mutations are exceedingly rare in cancer (0.7% overall), it seemed likely to the authors that the onset of scleroderma and the cancer genomes of these patients were related and that the mutations and T cell responses directed against them were not coincidental. Although just a handful of patients was studied, the findings suggest that a genetic mutation in some cancers can trigger a patient’s concurrent autoimmune disorder, scleroderma.8 Voilà! Perhaps these insights can be extrapolated to dermatomyositis as well.

The findings also raise some intriguing issues about the ability of some tumors with high mutation rates (e.g., lung, melanoma) or microsatellite DNA instability (e.g., colorectal) to cause autoimmunity.8 After all, aside from lymphoma, these are among the most common cancers that afflict our patients. Causal or coincidental?

A Balancing Act

Chronic inflammation, cancer and autoimmunity are inextricably linked, although their relationships remain poorly understood. A major hurdle is the fact that mechanisms of self-tolerance that prevent autoimmunity also impair T-cell responses against tumors, which do not differ substantially from self. However, upsetting the fine balance between cancer and autoimmunity can be hazardous. One need look no further than the warning labels of most of our biologic drugs. Thus, it’s encouraging to note the recent success of immunotherapy in treating some malignant disorders via blockade of the major checkpoint inhibitors, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1).9 In some conditions, one may even track patient outcomes by observing whether the cancer therapy induced an aberrant autoimmune response. Example: Patients with advanced forms of melanoma who developed a vitiligo-like skin depigmentation following immunotherapy were two to four times less likely to suffer disease progression or death, compared with treated patients without this development—paraneoplasia in reverse. I wish Maria were still around to hear this news. No doubt, she would have broken out another box of cannoli.

Simon M. Helfgott, MD, is associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

References

- Lyons AS, Petrucelli RJ. Medicine: An Illustrated History. New York, Abrams Inc. Publishers, 1978;216.

- Craig JW. Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy as the first symptom of pulmonary neoplasm. Brit Med J. 1937 Apr 10;1(3979):750–752.

- Dickinson CJ, Martin JF. Megakaryocytes and platelet clumps as the cause of finger clubbing. Lancet. 1987 Dec 19;2(8573):1434–1435.

- Manger B, Schett G. Paraneoplastic syndromes in rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014 Nov;10(11):662–670.

- Auche M. Des nevrites peripheriques chez les cancereux. Rev Med. 1890;10:785–807.

- Manger B, Schett G.s.Palmar fasciitis and polyarthritis syndrome—Systematic literature review of 100 case Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014 Aug;44(1):105–111.

- Joseph CG, Darrah E, Shah AA, et al. Association of the autoimmune disease scleroderma with an immunologic response to cancer. Science. 2014 Jan 10;343(6167):152–157.

- Teng MWL, Smyth MJ. Can cancer trigger autoimmunity? Science. 2014 Jan 10;343(6167):147–148.

- Boussiotis VA. Soamtic mutations and immunotherapy outcome with CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371(23):2230–2232.

- Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Jan 20;10.1200/JCO.2014.57.4756.

Correction

An astute reader, Martina Lilleston, brought an error to our attention. In Coding Corner, December 2014 TR, the final sentence stated: “The patient was injected with 20 mg of hyaluronate without ultrasound guidance.” It should have read, “The patient was injected with 20 mg of hyaluronate with ultrasound guidance.” The answer remains: 20611.

We regret the error.