Mrs. J was a 31-year-old woman with a five-year history of an overlap syndrome with features of systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis. Two months prior to the current admission, she had been hospitalized with altered mental status. At that time, she underwent brain imaging, lumbar puncture, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis and was diagnosed with lupus cerebritis. She was treated with corticosteroids, and her mental status improved to baseline. Her steroid dose was tapered over four weeks without recurrence of altered mental status.

Mrs. J was then admitted to the general medicine service with acute renal failure that was attributed to lupus nephritis. She was started on intravenous methylprenisolone at a dose of 125 mg daily. Over the next three days, she was unable to sleep and developed rapid, pressured speech. Usually mild mannered and cooperative with the nursing staff, she became irritable and suspicious. Psychiatry consultation was requested for assistance in evaluating and managing her acute behavioral changes.

Mrs. J had no previous psychiatric history aside from her recent episode of lupus cerebritis and had not been treated with antipsychotic or antidepressant medications in the past. There was no family history of psychiatric illness or rheumatologic disorders. She was married and lived with her husband and 10-year-old son. She was currently experiencing financial difficulties related to her health problems. She denied any use of alcohol, cigarettes, or illicit drugs, and urine toxicology was negative. She had been following up with her rheumatologist and primary care provider and had been taking medications as prescribed.

Because of the activity of the renal disease, Mrs. J’s rheumatologic condition necessitated continued use of corticosteroids, although the dose of prednisone was tapered to 60 mg daily. At the same time, risperidone was added at a low dose and titrated up to 0.5 mg in the morning and 2 mg at bedtime, with complete resolution of her manic symptoms. Over the next six months, she was able to be tapered off corticosteroids and risperidone without recurrence of the manic symptoms.

The outcome of this case was fortunately favorable, with treatment decisions requiring extensive discussion between the general medicine service and the patient’s consultants, including the rheumatologist, psychiatrist, and nephrologist. As often occurs with lupus patients who develop psychiatric symptoms when treated with glucocorticoids, two major questions arise: Are the psychiatric symptoms from the steroids as opposed to the disease (e.g., cerebritis)? If they are from steroids, how can these symptoms best be treated? This article will provide a framework to decide the answers.

Background

Corticosteroids are used to treat inflammatory manifestations of many rheumatologic conditions. Doses necessary to control disease are frequently high (e.g., 1 mg/kg or greater), and therapy may be maintained for prolonged periods of weeks to months. In this setting, one out of every two to three patients prescribed steroids may develop psychiatric symptoms including psychosis, mania, delirium, and depression. The most common symptoms reported with corticosteroid therapy are hypomania, mania, and psychosis.1

Psychiatric Symptoms Associated with Corticosteroids

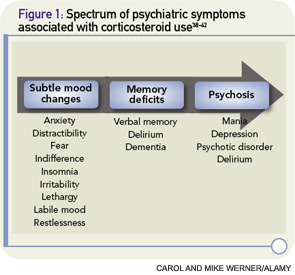

Psychiatric symptoms have been documented in association with the use of corticosteroids since these agents were first introduced in the 1950s.2 Corticosteroid-induced psychosis refers to a spectrum of psychiatric symptoms ranging from subtle mood changes to memory deficits to frank psychosis that can occur at any time during treatment (See Figure 1, p. 40).3 Mania and hypomania are reported most commonly (35%), followed by depressive symptoms (28%) and psychotic reactions (24%).2 Psychiatric symptoms typically develop three to four days after the initiation of corticosteroid therapy, although symptoms can occur at any time, including after cessation of therapy.

Symptoms may last a few days or persist for three weeks or more.2 A prospective study of outpatients with pulmonary disease who received 40 mg or more of corticosteroids for at least a week demonstrated a significant increase in measurable manic symptoms. The study also identified a subset of patients who developed dysphoric symptoms. These patients met criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder and were more likely to discontinue corticosteroids due to difficulties tolerating the mood symptoms.4

The pathophysiology of corticosteroid-induced psychosis remains poorly understood, although it is generally accepted that abnormalities of the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis can result in mood disorders. For example, syndromes involving excess or inadequate cortisol production can have psychiatric manifestations. Cushing’s syndrome is associated with anxiety, euphoria, depression, and psychosis, whereas Addison’s disease can produce fatigue, low energy, decreased appetite, and symptoms consistent with neurovegetative symptoms of depression.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the psychiatric community showed interest in the use of the dexamethasone suppression test for the diagnosis of endogenous versus characterologic depression. Although the test has not been incorporated into standard care, it nevertheless points to an important relationship between the regulation of glucocorticoid production and mood disturbance.5 Whether corticosteroid-associated psychiatric symptoms are related to hippocampal effects, suppression of the HPA by dopamine neurotransmission, or other direct or indirect effects of corticosteroids is not well understood.6-8

The primary risk factor for the development of corticosteroid-induced psychosis is a high dose of corticosteroids, with a sharp increase in risk among patients taking 40 mg of prednisone or its equivalent daily.4,9 Corticosteroid dosage, however, has not been correlated with onset, severity, type of reaction, or duration of psychiatric symptoms.3,9 Corticosteroid-induced psychosis is more common in women than in men. A history of psychiatric disorders or previous corticosteroid-induced psychosis is not predictive of future episodes.3

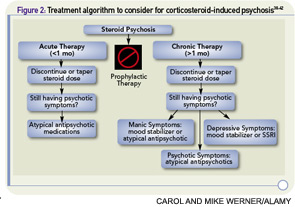

Treatment of Corticosteroid-Induced Psychosis

Whenever possible, tapering corticosteroids is recommended as a first step to manage corticosteroid-induced psychosis. Decreasing to the lowest dose possible, ideally less than 40 mg daily, or tapering and discontinuing steroids may be sufficient to improve psychiatric symptoms without requiring additional medications. In severe cases of affective instability or psychosis or if steroids cannot be tapered or discontinued, it may be necessary to employ off-label psychopharmacologic treatment. There is some evidence from open-label trials and case reports to support a role for antipsychotics and mood stabilizers. Studies with anticonvulsants have not supported their use.10–22

Although there is evidence to support mood stabilizers such as valproic acid, carbamazepine, and lithium in the treatment of steroid psychosis, the use of these medications can be complicated in medically ill patients.3 Of these three medications, valproic acid would be the most reasonable choice; however, this has been associated with pancreatitis and thrombocytopenia, and monitoring of liver enzymes is recommended. Because of possible drug interactions, carbamazepine, a potent inducer of cytochrome P450 isoenzyme activity, can be complicated to use in patients taking prednisone and other medications. Carbamazepine also requires monitoring for agranulocytosis and the possible development of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone section (SIADH).

Because many patients prescribed corticosteroids have rheumatological illnesses that affect renal function, lithium may be difficult to use safely in this patient population. Lithium has a narrow therapeutic index, is metabolized through the kidneys, and is not safe for use with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or diuretics. Although antipsychotics also have risks, including increased risk for the development of the metabolic syndrome and QTc prolongation, using these medications at the lowest effective dose for the minimum necessary duration can be an effective strategy to treat steroid psychosis.

Antipsychotics

There is general support for the use of low-dose atypical antipsychotic agents when symptoms are severe or when tapering steroids is not feasible; the specific drug or dose recommendation is informed by personal preference of the provider as well as by limited evidence. In a five-week, open-label trial of 12 outpatients experiencing manic or mixed symptoms associated with corticosteroid use, olanzapine was associated with significant reductions in psychiatric symptoms on the Young Mania Rating Scale, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.16 There were no statistically significant differences in weight or blood glucose, although it is important to note that this was a small trial of short duration and, on average, patients gained five pounds in five weeks on this medication. Case reports of olanzapine indicate that starting at a low dose (e.g., 2.5 mg) and titrating up to a moderate dose (e.g., 10–15 mg) daily can be effective in alleviating symptoms.15–17

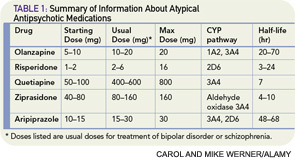

There are four case reports describing a benefit from risperidone, with doses ranging from 1 to 4 mg daily, in adults and children with a variety of psychiatric symptoms, including hypomania, hallucinations, and delusions associated with corticosteroid therapy.18–21 In these patients, symptoms improved within days to weeks. One case report described the successful use of quetiapine 25 mg daily with a 12.5-mg as-needed dose for the treatment of corticosteroid-induced mania.22 No case reports exist for ziprasidone or aripiprazole. Table 1 (p. 41) contains information about dosing, metabolism, and half-life of the atypical antipsychotics. Of the typical (first generation) antipsychotics, there are case reports for the use of low-dose haloperidol (2–5 mg daily)23 and chlorpromazine (150 mg daily).24

Monitoring Considerations

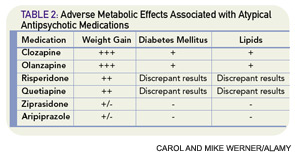

The use of atypical antipsychotics has been associated with the development of the metabolic syndrome (see Table 2, p. 41). The American Psychiatric Association, American Diabetic Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and American Association for the Study of Obesity coauthored guidelines for suggested monitoring of patients prescribed these agents.25 Before starting atypical antipsychotics, baseline personal and family history along with body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, and fasting lipid profile should be obtained. Weight should be monitored monthly for the first three months and then quarterly, and blood pressure and fasting glucose should be rechecked (and treated, if abnormal and unable to taper off the antipsychotic medication) after three months and then annually while prescribed the medication.25

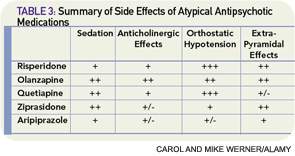

Atypical antipsychotics are also associated with various side effects, and monitoring for development of extrapyramidal side effects is recommended (see Table 3, above). Given the adverse side-effect profile and off-label use, these medications should be used at the lowest effective dose for the shortest effective duration. Though there are no clear monitoring recommendations, all antipsychotics can prolong the QTc interval.

Mood Stabilizers

A retrospective cohort study examined records of patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis or retrobulbar neuritis who were treated with corticotrophin and assessed their outcomes based on whether or not they received prophylactic lithium therapy.13 Psychiatric symptoms developed in 38% of patients treated with lithium at doses to maintain serum levels between 0.8 and 1.2 mEq/L compared with 62% of controls, and none of the lithium-treated patients developed frankly psychotic symptoms. There are also case reports describing the use of lithium, valproic acid, and carbamazepine as prophylaxis or as treatment of corticosteroid-induced psychosis.26–33 Unfortunately, the lack of controls makes interpretation of these reports difficult, particularly because previous history of corticosteroid-induced psychosis is not reliably predictive of future development of the same symptoms.3

Antidepressants

The use of antidepressants may be considered when patients report significant depressive symptoms associated with corticosteroid therapy. It is important to note a few issues when choosing a medication. First, any time an antidepressant medication is initiated, it is important to screen for a history of mania, such as by using the screening question: “Have you had periods of feeling so happy or energetic that your friends told you were talking too fast or that you were too ‘hyper’?”34 Second, many of the antidepressants are metabolized through the cytochrome P450 iso-enzyme family and may have relevant potential drug–drug interactions. Third, especially in elderly patients, antidepressants can be associated with adverse effects.

One adverse effect that has been seen with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), especially in the elderly patients, is the development of SIADH; there is also some literature associating SSRIs with increased falls as well as literature suggesting an association between SSRI use and osteoporotic fracture risk. Lastly, patients should not discontinue medications abruptly and need to be counseled about symptoms of discontinuation syndrome. Even in light of these cautions, in the instance of corticosteroid-induced depressive symptoms, there is support in the literature for the use of SSRIs. In choosing an SSRI, paroxetine and fluoxetine are most likely to have significant drug–drug interactions through the cytochrome P450 iso-enzyme family, particularly 2D6 and 3A4. Sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram do not significantly induce or inhibit cytochrome P450 activity.

The literature raises specific concern about possible adverse effects of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), with observations of symptom exacerbation in patients with corticosteroid-induced psychosis treated with TCAs. For this reason, TCAs are not recommended for use in steroid-induced mood symptomatology.

There is general support for the use of low-dose atypical antipsychotic agents when symptoms are severe or when tapering steroids is not feasible.

Anticonvulsants

Published studies of anticonvulsants including phenytoin, levetiracetam, and lamotrigine have not demonstrated benefit from the use of these agents in preventing corticosteroid-induced psychosis.10-12 Case reports exist supporting the use of lamotrigine and gabapentin.35,36 However, lamotrigine may be difficult to use because it must be started at a very low dose and titrated slowly over weeks to months to the target dose. The use of gabapentin in psychiatric disorders, particularly bipolar disorder, has not been shown to be effective.37

Summary and Recommendations

Establishing a treatment algorithm (see Figure 2, p. 41) for corticosteroid-induced psychosis is difficult given the lack of high-quality prospective trials. However, most case reports describe benefit from atypical antipsychotics and lithium. With appropriate monitoring, a low-dose atypical antipsychotic such as olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine can be helpful in alleviating symptoms of steroid-induced psychosis. In select patients without renal insufficiency or the need for diuretic, ACE inhibitors, or NSAID therapy, lithium may be used but requires careful monitoring and vigilance for signs of toxicity. When patients cannot tolerate atypical antipsychotics or lithium, valproic acid or carbamazepine with appropriate monitoring may be useful alternatives. SSRIs may be helpful in patients with depressive symptomatology without a history of mania, but there is some evidence that tricyclic antidepressants may exacerbate the symptoms.

Dr. Gagliardi is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and assistant professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, N.C. Dr. Muzyk is an assistant professor and Dr. Holt is a pharmacy resident at Campbell University School of Pharmacy and Health Sciences in Buies Creek, N.C.

References

- Bolanos SH, Khan DA, Hanczyc M, et al. Assessment of mood states in patients receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy and in controls with patient-rated and clinician-rated scales. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92:500-505.

- Sirois F. Steroid psychosis: A review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:27-33.

- Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effect of corticosteroids. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1361-1367.

- Brown ES, Suppes T, Khan DA, Carmody III TJ. Mood changes during prednisone bursts in outpatients with asthma. J Clinical Psychopharm. 2002;22:55-61.

- Brown WA, Johnston R, Mayfield D. The 24-hour dexamethasone suppression test in a clinical setting: Relationship to diagnosis, symptoms, and response to treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:543-547.

- Naber D, Sand P, Heigl B. Psychopathological and neuropsychological effects of 8-days’ corticosteroid treatment. A prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996; 21:25-31.

- Brown ES, Woolston DJ, Frol A, et al. Hippocampal volume, spectroscopy, cognition, and mood in patients receiving corticosteroid therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:538-545.

- Schatzberg AF, Rothschild AJ, Langlais PJ, et al. A corticosteroid/dopamine hypothesis for psychotic depression and related states. J Psychiatr Res. 1985;19:57-64.

- The Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. Acute adverse reactions to prednisone in relation to dosage. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972;13:694-698.

- Brown ES, Stuard G, Liggin JD, et al. Effect of phenytoin on mood and declarative memory during prescription corticosteroid therapy. Bio Psychiatry. 2005;57:543-548.

- Brown ES, Frol AB, Khan DA, et al. Impact of levetiracetam on mood and cognition during prednisone therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:448-452.

- Brown ES, Frol A, Bobadilla L, et al. Effect of lamotrigine on mood and cognition in patients receiving chronic exogenous corticosteroids. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:204-208.

- Falk WE, Mahnke MW, Poskanzer DC. Lithium prophylaxis of corticotropin-induced psychosis. JAMA. 1979;241:1011-1012.

- Goldman LS, Goveas J. Olanzapine treatment of corticosteroid-induced mood disorders. Psychosomatics. 2002; 43:495-497.

- Brown ES, Khan DA, Suppes T. Treatment of corticosteroid-induced mood changes with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:968.

- Brown ES, Chamberlain W, Dhanani N, et al. An open-label trial of olanzapine for corticosteroid-induced mood symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2004;83:277-281.

- Budur K, Pozuelo L. Olanzapine for corticosteroid-induced mood disorders. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:353.

- Herguner S, Bilge I, Yavuz Yilmaz A, et al. Steroid-induced psychosis in an adolescent: Treatment and prophylaxis with risperidone. Turk J Pediatr. 2006;48:244-247.

- DeSilva CC, Nurse MC, Vokey K. Steroid-induced psychosis treated with risperidone. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47: 388-389.

- Kato O, Misawa H. Steroid-induced psychosis treated with valproic acid and risperidone in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7:312.

- Kramer TM, Cottingham EM. Risperidone in the treatment of steroid-induced psychosis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999;9:315-316.

- Siddiqui Z, Ramaswamy S, Petty F. Quetiapine therapy for corticosteroid-induced mania. Can J Psychiatry. 2005; 50:77-78.

- Ahmad M, Rasul FM. Steroid-induced psychosis treated with haloperidol in a patient with active chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [letter]. Am J Emergency Med. 1999;17:735.

- Bloch M, Gur E, Shalev A. Chlorpromazine prophylaxis of steroid-induced psychosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994; 16:42-44.

- Boehm G, Racoosin JA, Laughren TP, Katz R. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004; 27:596-601.

- Siegal FP. Lithium for steroid-induced psychosis. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:155-156.

- Goggans FC, Weisberg LJ, Koran LM. Lithium prophylaxis of prednisone psychosis: A case report. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44:111-112.

- Sabet-Sharghi F, Hutzler JC. Prophylaxis of steroid-induced psychiatric syndromes. Psychosomatics. 1990;31:113-114.

- Merrill W. Case 35-1998: Use of lithium to prevent corticosteroid-induced mania. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1123.

- Abbas A, Styra R. Valproate prophylaxis against steroid induced psychosis. Can J Psychiatry. 1994;39:188-189.

- Himelhoch S, Haller E. Extreme mood lability associated with systemic lupus erythematosus and stroke successfully treated with valproic acid. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16:469-470.

- Kahn D, Stevenson E, Douglas CJ. Effect of sodium valproate in three patients with organic brain syndromes. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;145:1010-1011.

- Wada K, Yamada N, Yamauchi Y, et al. Carbamazepine treatment of corticosteroid-induced mood disorder. J Affect Disord. 2001;65:315-317.

- Carlat DJ. The psychiatric review of symptoms: A screening tool for family physicians. Am Fam Phys. 1998;58:1617-1624.

- Preda A, Fazeli A, McKay BG, Bowers MB, Mazure CM. Lamotrigine as prophylaxis against steroid-induced mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:708-709.

- Ginsberg DL, Sussman N. Gabapentin as prophylaxis against corticosteroid-induced mania. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;44:455-456.

- Pande AC, Crockatt JG, Janney CA, Werth JL, Tsaroucha G. Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: A placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy. Gabapentin Bipolar Disorder Study Group. Bipolar Disord. 2000; 2:249-255.

- Cheer SM, Wagstaff AJ. Quetiapine: A review of its use in the management of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:173-199.

- Bowles TM, Levin GM. Aripiprazole: A new atypical antipsychotic drug. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:687-694

- Caley CF, Cooper CK. Ziprasidone: The fifth atypical antipsychotic. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:839-851

- Livingston MG. Risperidone. Lancet 1994;343:457-460.

- Fulton B, Goa KL. Olanzapine: A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in the management of schizophrenia and related psychoses. Drugs. 1997;53:281-298.