Checking random drug levels is generally only useful for drugs with very long half-lives and low within-day variability. Azathioprine metabolites (half-life of approximately five days) and most subcutaneous biologic drugs (apart from anakinra) fall into this category.3

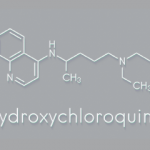

Checking random drug levels of other medications for the purpose of identifying medication adherence can sometimes be useful when concentrations are at the extremes. For example, undetectable drug levels often imply some degree of medication nonadherence. Many recent publications, particularly those studying HCQ, have relied on random drug levels. However, recent data suggest that HCQ levels change by about 30% within a day, significantly limiting the interpretation of these studies and highlighting the need to study trough levels.4 Mycophenolic acid can undergo absorption more than once (enterohepatic recirculation), resulting in erratic time vs. concentration profiles and the need to measure AUC as opposed to a peak, trough or random concentration.

Although asking patients to take their medication at a specific time is ideal so you can measure a timed sample (e.g., peak or trough) when they see you in clinic, patients can find this difficult, logistically speaking. However, by asking your patient when they took their last dosage, it is possible, in most cases, to measure a random drug level and ballpark where they are in the dosing interval—near the peak, trough or somewhere in between. This strikes a reasonable balance between practicality and interpretability in most cases.

Step 2: Dose Matters

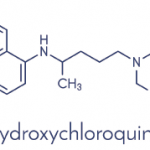

Most DMARDs (except certain biologics, particularly at low doses) follow linear pharmacokinetics, meaning dose is directly proportional to drug exposure (Cmax, Cmin, AUC). For example, a patient receiving 150 mg of a medication would be expected to have twice the Cmax as somebody receiving 75 mg of the same medication (see Figure 1). Therefore, when comparing a medication blood level for your patient to a target level from the literature, it is important to consider whether the dose your patient is receiving is similar to doses in the research study. This also means that drug level thresholds used to identify medication non-adherence are also dose specific.

A quick note on weight-based dosing: A common pitfall in our community is assuming that normalizing dosage based on weight (e.g., 5 mg/kg of HCQ or 2 mg/kg of azathioprine) will ensure a diverse group of patients will all achieve comparable drug levels. Unfortunately, studies have shown a very poor correlation between weight-based dosing and drug levels for HCQ (R2=0.03)5 and azathioprine/6-MP (r=0.17).6 The reasons for the poor correlation are complex, but weight-based dosing assumes a linear relationship between body weight and dose, whereas in reality drug clearance often follows an allometric (power) relationship. However, in children, weight-based dosing is still important for many drugs.