Although outside the scope of this tutorial, our future practices will likely be heavily influenced by the rapidly growing field of pharmacogenomics and pharmacokinetics modeling, which may help us individualize drug dosing by identifying which patients require dosage adjustments and providing the bedside clinical decision tools to change dose.

Putting It All Together

For DMARDs in rheumatology, the two most common reasons to check drug levels are to gauge adherence to medication and to identify whether patients are achieving a therapeutic or toxicity threshold requiring a dosage adjustment, especially in states of altered states of physiology (e.g., renal dysfunction, gastric bypass) or in the presence of an anti-drug antibody. Additional reasons may include exploring reasons for primary or secondary non-response, or to guide tapering decisions. Table 1 provides a high-level (and nonexhaustive) summary of published drug level targets across several biologic and non-biologic DMARDs; more extensive summaries have been published elsewhere.7

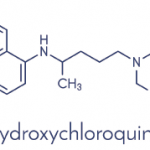

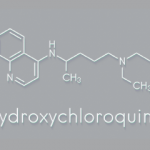

Identifying medication non-adherence is crucial because it avoids the common scenario where a non-adherent patient may appear to fail multiple different treatments and be labeled as having treatment-refractory disease. Moreover, counseling interventions have been shown to improve adherence and result in higher systemic drug levels.2 In general, a good case can be made to check drug levels when a patient is not responding to treatment, although some clinicians check drug levels routinely as part of their practice. As outlined in Table 1, HCQ has the best data with medication non-adherence. However, due to high variability in HCQ pharmacokinetics, an algorithm has been proposed to optimally relate HCQ blood levels with the number of missed doses.4

Additional data are needed before most DMARDs can be routinely dose-adjusted to achieve target levels based on efficacy or toxicity, with the strongest data for tacrolimus (not covered in this tutorial) and biologic drugs. For example, a recent randomized controlled trial found that patient’s achieving a 3–8 μg/mL trough level of infliximab had higher rates of remission compared to usual care.9 Algorithms have been proposed for tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors to help guide the decision on whether non-responders should have a dosage increase, be switched to a biologic of the same drug class or be switched to a different drug class.10 A clinical trial in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus and HCQ blood levels between 100 and 750 ng/mL were randomized to usual care vs. dose escalation to a blood HCQ level of ≥1,000 ng/mL; the study found no significant difference in flare rates over seven months.11 However, there were observed changes in medication adherence, and most patients randomized to dose escalation did not achieve the target HCQ level. In subgroup analyses, patients who consistently maintained HCQ levels ≥1,000 ng/mL had significantly fewer flares (excluding flares within one month of randomization). For mycophenolate, ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the efficacy of AUC guided dosing vs. standard dosing in children with SLE.