The economic implications of biologic therapies are staggering. In 2009, 75% of small molecules (pills and capsules) dispensed were in generic form. By contrast, biologic medications account for 43% of the Medicare Part B budget! When will generic biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) become commercially available?

Biosimilar Basics

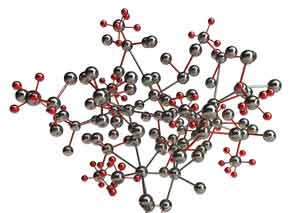

The term for a “generic biologic” is “biosimilar.” What is a biosimilar? It is a product that is highly similar to the “innovator” product, or brand-name biologic DMARD. Biologic DMARDs are different from small molecules in several important dimensions:

- These are high-molecular-weight molecules with complicated, and unique, tertiary and quartenary structures. In other words, conformational changes in structure are important for function.

- They are manufactured using recombinant DNA technology, which typically incorporates posttranslational modifications, especially glycosylation (if produced in mammalian cell lines).

- Because they are protein molecules, they are immunogenic, to varying degrees.

- Rather than being metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, they are catabolized.

- Given the parenteral administration required for protein molecules, the dose–response curves are nonlinear and sometimes less predictable than those seen with small molecules.

For these incredibly complex protein molecules, there are issues that do not apply to small molecule generics. For example, the manufacturing process for biologic DMARDs is much more complex than for small molecules, requiring large bioreactors and detailed, complicated biochemical processes. Purification of the final product is far more complex, and there are stability issues for these protein medications that do not apply to small molecules.

Biologics Go Global

Although patent expiration in the U.S. for several biologic therapies may be several years away (etanercept’s patent expires in 2026, infliximab’s and rituximab’s in 2018, adalimumab’s in 2017), biosimilars for these products are currently under development. In countries where the regulatory environments are much less stringent than in the U.S. or Europe, there already exist “bio-alike” products. In these countries (listed in Table 1), the cost of development has been significantly reduced, in part because randomized controlled trials to formally demonstrate equivalency have not been required.

Though these products have not undergone the stringent regulatory reviews required in the U.S., E.U., Canada, or Australia to demonstrate biosimilarity, economic pressures have propelled their development in those countries listed in Table 1.

Accordingly, in 2009 Congress passed legislation to address the process of bringing biosimilars to the U.S. market as part of healthcare reform. Termed the Biologics Price Competition and Innovative Act, this legislation defines the requirements for a biosimilar compared to the original “innovator” product as follows:

- Must be “highly similar” to the original product;

- Must involve the same mechanism of action;

- Must have no clinically meaningful differences in potency, purity, or toxicity;

- Must be expected to produce the same clinical results; and

- Must utilize the same route of administration, dose, and strength.

A biosimilar may be determined to be sufficiently similar (i.e., “highly similar”) to the innovator product when it can be interchangeable with the original, such that no significant differences would be expected to occur if the patient were to be switched back and forth between the innovator drug and the biosimilar.