In the JAMA paper, Dr. Schmajuk and colleagues raise the issue that significant comorbidities as well as quiescent disease are both valid reasons for a patient with RA to not receive DMARD therapy. However, current estimates suggest only 10%–15% of patients with RA meet these conditions. The treatment gap identified in Medicare patients brings a bigger question to the forefront: What is the appropriate quality goal for DMARD use for which rheumatologists should be held accountable?

Study co-author Daniel Solomon MD, MPH, director of health services research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and a member of The Rheumatologist’s editorial board, notes that the National Center for Quality Assurance standard in its current form, which suggests everyone with RA be prescribed a DMARD, is a disconnect from real-world rheumatology practice. “Optimal DMARD rates are closer to 90%. General clinical consensus is that for 1 in 10 patients, comorbid conditions or the emergence of life-threatening side effects does not justify DMARD treatment, despite the potential for better outcomes.”

The role of quiescent disease in establishing RA quality measures is more complicated. “Quiescent disease is a different issue than inducing remission in rheumatoid arthritis,” says Dr. Solomon. “Patients with palindromic disease who have episodes and remit are rare. Typical rheumatoid arthritis does not remit. We know too little about the frequency of drug-free remission right now to know how it should impact DMARD quality goals.” Numerous clinical trials are ongoing currently that examine whether putting people in remission early in disease can result in a drug-free remission state. At present, patients whose disease is inactive to the degree of not needing DMARD therapy are rare and should not factor into RA quality standards.

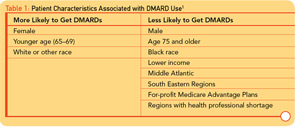

“A limitation of claims data is that we don’t know how many patients have ‘true, active rheumatoid arthritis’; it’s hard to say what an appropriate quality goal is with Medicare/HEDIS data since patients are not required to see a rheumatologist,” says Dr. Schmajuk. “Regardless of the ‘correct’ quality performance rate, reduced DMARD access as we observed in the study, based on nonclinical factors such as health plan, geography, socioeconomic status, gender, and race, is unacceptable.”

Moving Beyond Individual Practice

“Rheumatologists aren’t the problem,” says Dr. Solomon. “If you go to a rheumatologist, you will get a DMARD. The age disparity is not particularly relevant to the individual rheumatologist in his or her practice.” Agreeing with Dr. Solomon, Dr. Schmajuk doubts that the age treatment gap is attributable to rheumatologists. “Prior studies from the United States and Europe show that most patients seen regularly by rheumatologists are being treated appropriately.”