Rheumatology caught the attention of the broader medical community with an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association showing that only 63% of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients in Medicare Advantage programs received disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) from 2005 to 2008.1 Lower than the overall DMARD use rates reported by the National Center for Quality Assurance in 2008, which range from 70% for Medicare plans to 85% for commercial plans, a treatment gap is apparent for RA patients age 65 years and older. Given the average age of diagnosis for RA is 60 years, this age-related gap is disconcerting.

The good news is that the RA treatment gap in older patients is already narrowing. “The fact that 67% of the Medicare patients were on DMARDs in 2008, up from 59% in 2005, is progress,” says Stanley Cohen, MD, clinical professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas and past president of the ACR. However, the bad news is that DMARD use rates varied from 16% to 87% across Medicare Advantage plans.

Economics plays a significant factor for healthcare plans and patients. Patients in for-profit Medicare Advantage plans were less likely to get DMARD therapy than those in not-for-profit plans. Lead author of the JAMA study Gabriela Schmajuk, MD, MS, rheumatology instructor at Stanford University in Stanford, Calif., notes this finding is not unique. Studies of quality measures consistently find lower performance rates among for-profit plans compared with not-for-profit plans, even after adjusting for patient characteristics.

Despite the Medicare coverage for prescriptions, a substantial burden of cost still remains with patients. Patients enrolled in Medicare Advantage programs pay 28% of DMARD medication costs. Biologic therapy can cost a patient upwards of $4,000 annually out of pocket with Medicare.2 Not surprisingly, lower income is a barrier to DMARD access. Only 55% of patients with low incomes receive treatment, compared with 64% of patients with higher incomes.

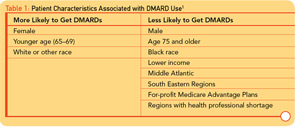

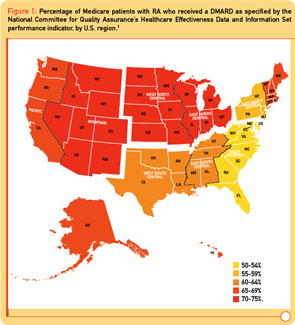

Two surprising additional findings were large geographic variations in DMARD use and a 10%–30% decrease in DMARD use in patients age 75 years and older relative to patients age 65 to 69 years. In the Middle Atlantic and Southeastern states, DMARD use is significantly lower (8%–15%) than the rest of the United States (see Figure 1). Additional factors associated with decreased DMARD use were male sex, black race, and lower socioeconomic status (see Table 1).

Reflecting Real Life in Quality Measures

The large age disparity, with only 13% of RA patients age 85 years and older receiving DMARD therapy, raises the question of what are appropriate target rates for DMARD use among various RA patient populations. Dr. Cohen notes, “In a patient who is 87 years old with mild disease, we clinicians are not worried about progressive disability in 20 years. If they have diabetes, chronic heart disease, or lung disease, we choose not to treat them with a DMARD.”

In the JAMA paper, Dr. Schmajuk and colleagues raise the issue that significant comorbidities as well as quiescent disease are both valid reasons for a patient with RA to not receive DMARD therapy. However, current estimates suggest only 10%–15% of patients with RA meet these conditions. The treatment gap identified in Medicare patients brings a bigger question to the forefront: What is the appropriate quality goal for DMARD use for which rheumatologists should be held accountable?

Study co-author Daniel Solomon MD, MPH, director of health services research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and a member of The Rheumatologist’s editorial board, notes that the National Center for Quality Assurance standard in its current form, which suggests everyone with RA be prescribed a DMARD, is a disconnect from real-world rheumatology practice. “Optimal DMARD rates are closer to 90%. General clinical consensus is that for 1 in 10 patients, comorbid conditions or the emergence of life-threatening side effects does not justify DMARD treatment, despite the potential for better outcomes.”

The role of quiescent disease in establishing RA quality measures is more complicated. “Quiescent disease is a different issue than inducing remission in rheumatoid arthritis,” says Dr. Solomon. “Patients with palindromic disease who have episodes and remit are rare. Typical rheumatoid arthritis does not remit. We know too little about the frequency of drug-free remission right now to know how it should impact DMARD quality goals.” Numerous clinical trials are ongoing currently that examine whether putting people in remission early in disease can result in a drug-free remission state. At present, patients whose disease is inactive to the degree of not needing DMARD therapy are rare and should not factor into RA quality standards.

“A limitation of claims data is that we don’t know how many patients have ‘true, active rheumatoid arthritis’; it’s hard to say what an appropriate quality goal is with Medicare/HEDIS data since patients are not required to see a rheumatologist,” says Dr. Schmajuk. “Regardless of the ‘correct’ quality performance rate, reduced DMARD access as we observed in the study, based on nonclinical factors such as health plan, geography, socioeconomic status, gender, and race, is unacceptable.”

Moving Beyond Individual Practice

“Rheumatologists aren’t the problem,” says Dr. Solomon. “If you go to a rheumatologist, you will get a DMARD. The age disparity is not particularly relevant to the individual rheumatologist in his or her practice.” Agreeing with Dr. Solomon, Dr. Schmajuk doubts that the age treatment gap is attributable to rheumatologists. “Prior studies from the United States and Europe show that most patients seen regularly by rheumatologists are being treated appropriately.”

The underutilization of DMARD therapy likely lies in perceptual misconceptions among primary care and internal medicine physicians for elderly patients. “Unfortunately, front-line providers perceive that older patients are too old, frail, sick, to receive DMARDs,” says Dr. Solomon. Consequently, older patients with RA are not getting referred for rheumatology care.

Lack of exposure to DMARDs during medical training is a large contributor to perceptual biases in primary care regarding RA in older patients. “Primary care thinks DMARDs are too toxic, hard to monitor, and patients are too sick for these treatments because they’re not giving these drugs every day and are not familiar with the side effects,” he says. In a forthcoming survey about primary care providers, Dr. Solomon notes, a large number of primary care providers state that they will not prescribe a DMARD under any circumstances. Fortunately, many clinicians in primary care will do DMARD maintenance therapy if initiated by a specialist.

Drs. Schmajuk and Solomon recognize that closing the RA treatment gap requires going beyond the rheumatology community. “We don’t have a simple solution to this issue, but we have to think beyond our practice,” says Dr. Solomon.

Immediate next steps are two-fold for improving quality of care in patients age 65 and older. “First, educate internists and primary care doctors on the need for DMARDs, and not just corticosteroids or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis,” says Dr. Schmajuk. “Second, encourage patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and their providers to seek care from a rheumatologist.”

A longer-term view towards solving the RA treatment gap is also needed given the impending rheumatologist shortage in next decade forecasted by the ACR’s U.S. Rheumatology Workforce Study.3 “Over the next decade, access for patients with rheumatoid arthritis to rheumatologists and appropriate care with DMARDs is going to get more challenging than even the current environment,” notes Dr. Solomon. “As rheumatologists, we’ll need to figure out better systems of care to safely prescribe DMARDs, where we co-manage patients with nonrheumatologists. We’ll need to work more closely with primary care since they are going to be front-line providers for these patients who are not going to all be able to get in and see rheumatologists.”

Dr. Solomon admits that, “fundamentally, it’s an overhaul of our healthcare systems.” In an admittedly daunting task, the first step will be identifying models that work. “Presently no evidenced-based models exist yet for improving DMARD use in a given community,” he says.

Rheumatologists are delivering high-quality care for RA patients, and the current treatment gaps are largely attributed to factors outside the professional rheumatology community. Yet rheumatologists are best poised to lead the efforts to improve the quality of care for older rheumatoid arthritis patients at a public health level. “As a profession, it’s time to start thinking more creatively about how we disseminate our expertise in the current system of healthcare,” notes Dr. Solomon. “Whether it’s collaborating more, and exploring co-management models with primary care, our expertise needs to be more broadly applied.”

Heather Haley is a medical writer based in Cincinnati, Ohio.

References

- Schmajuk G, Trivedi AN, Solomon DH, et al. Receipt of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Medicare managed care plans. JAMA. 2011;305:480-486.

- Polinski JM, Mohr PE, Johnson L. Impact of Medicare Part D on access to and cost sharing for specialty biologic medications for beneficiaries with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:745-754.

- Deal CL, Hooker R, Harrington T, et al. The United States Rheumatology Workforce Study: Supply and demand, 2005–2025. Arthritis Rheum. 2007; 56:722-729.