Photos courtesy of Matthew Taylor

My 24 years of fishing have made me a better rheumatologist, because fishing (especially fly fishing) is the ideal sport for a rheumatologist.

Before you conclude that I have been out in the sun too long, let me explain. Both fishing and practicing rheumatology are complicated processes, requiring inquiry, study, and contemplation. When I fish, I examine the weather, the depth and speed of the water, the contour of the stream bed, the time of year, and the predominant insects above and below the water. It’s a bit like taking a history and physical to try to make a rheumatologic diagnosis. With this information, I plan my approach, recognizing that the “right” fly and presentation will not always work, for reasons which are unknown, and that it will likely be necessary to try a different approach. Treating rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) is similar: we know which medications work, but we don’t know in which patients the result will be successful, and often we must try something besides the medication that seemed like the right one to use first.

The sport is not called “catching fish” because most of the time we are not actually doing that; we are fishing, or engaged in the endeavor in which we aspire to catch fish. I think that is quite similar to practicing rheumatology, where we have relatively few golden moments in which we do something to make a patient profoundly better. Rather, it is an incremental process of understanding the patient’s problems and trying one thing after another in an effort to improve their quality of life. We enjoy the process of trying to figure out what is wrong, and what to do to make it better, while getting to know the patient and their family and job.

It occurred to me one day while not catching fish that both fishing and practicing rheumatology require enormous patience. That is obvious, but like many realizations that seem obvious, embracing and taking it to heart has enriched my understanding that in treating our patients, we are really in it for the long haul, and it is much more satisfying if we can enjoy the process. Each session in the stream, or the exam room, entails a process that I have come to enjoy and treasure for its own sake, with the added joy of catching a nice fish, or finding the DMARD that finally works for someone’s RA.

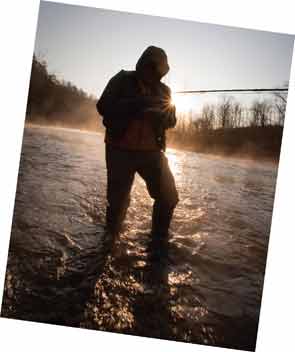

But the main reason I go fishing is for the peace of mind, the ability to get away from the toils and troubles of daily life. While wading on slippery rocks, trying hard not to fall into 55-degree water, listening to the water rushing around my legs, and enjoying all the beauty above and below the water, I can go to a very special, serene place, where I empty my mind and think about nothing. It is a Zen-like experience, letting go of all that is not important at that moment in the water. It helps me get “centered,” whatever that means.

When Thoughts Intrude

Only twice can I recall the intrusion of thoughts that disrupted this state. One was a problem at work, which I realized I had to fix immediately so I could fish in peace. The second occurred after one of the debates in the recent Presidential campaign. I realized that universal access to healthcare is very important to me, and was troubled that so many other people did not share this view. Why did I believe this, and how could I explain my point of view to another person in a thoughtful and rational sort of way? For the next hour, I fished without success and could not get this issue off my mind, so I got out of the water, and decided that I needed to work this out.

First, I have a couple of disclosures to acknowledge. I am a life-long Democrat, and come by it honestly. My mother told me that when she was growing up in Buncombe County in western North Carolina, there was no Republican party. Although you probably don’t realize it, my home county most likely has entered your vocabulary. In 1820, Felix Walker was our notoriously long-winded Congressman, and insisted on delivering a long and tedious speech “for Buncombe” during the debate on whether to admit Missouri (my current state) as a free or slave state. A Washington, D.C., newspaper published his speech, and “buncombe” or “bunkum” came to refer to bombastic political oratory directed to the speaker’s constituency, without any prospect of contributing to useful debate. We have certainly heard a lot of that from BOTH parties in the last few years.

Second, I have never been in a true “private practice,” by which I mean running a small business as a single or small group of physicians. Since graduating from medical school, I have worked as a salaried employee, and have been largely insulated from the financial implications of which patients I see and how I practice. I have not had to balance a budget for a practice, ensure that there is enough revenue to make payroll for my employees, negotiate with insurance companies for reimbursement, and figure out how to buy health insurance for my employees. I freely acknowledge that I am woefully ignorant of the realities therein. Some of my fellows and patients have helped me understand some of these issues.

So, I acknowledge my biases at the outset. However, my comments are not meant to be a polemic so much as a contemplation of why one would, or would not, favor universal access to healthcare. This is not an argument for Obamacare, Medicare for All, single-payer insurance, or any specific proposal. I support the Affordable Care Act, with its many flaws, but for this discussion, that is beside the point. I am also not trying to address the issue of spending large sums of money on healthcare as we address the federal deficit; that is a very complicated issue and I don’t pretend to have the solution.

A Suggested Goal for Our Healthcare System

I do not believe that healthcare is a “right,” as so many argue. To my mind, a “right” is something articulated by rigorous philosophical argument, or something contained in the Constitution or Bill or Rights. I think that arguing over whether access to healthcare is a “right” distracts us from the more important question of whether we believe that everyone should have adequate access to healthcare or not. In what kind of society do we want to live? Virtually all citizens of modern societies embrace ideas of justice and fairness and equality as “these truths we find self-evident,” as the Founding Fathers said. Should that include universal access to healthcare?

I had the good fortune in college to study under Robert Nozick and John Rawls, two philosophy professors who have had important impacts on contemporary philosophy, although with opposing views. Nozick articulated the libertarian philosophy and made a cogent argument for fierce individualism, in which one’s property, money, or possessions could not be expropriated by society or government for any reason.

“A minimal state, limited to the narrow functions of protecting against force, theft, fraud, enforcement of contracts, and so forth, is justified …the state may not use its coercive apparatus for the purpose of getting some citizens to aid others.”—Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia

In fact, Nozick’s treatise, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, was in large part written to counter the views of Rawls (discussed below). I was not sympathetic to Nozick’s view, but because I found him so engaging and clever, I did take his course on “The Meaning of Life”: my grade was B+.

Rawls’ treatise, A Theory of Justice, is considered to be one of the seminal works of modern political philosophy, in which he attempted to elaborate on the traditional theory of the social contract. Rawls’ goal was to find a method for constructing a “just society,” and he did so by describing the concept of the “original position.”

“This original position is understood as a purely hypothetical situation characterized so as to lead to a certain conception of justice. Among the essential features of this situation is that no one knows his place in society, his class position or social status, nor does any one know his fortune in the distribution of natural assets and abilities, his intelligence, strength, and the like The principles of justice are chosen behind a veil of ignorance. This ensures that no one is advantaged or disadvantaged in the choice of principles by the outcome of natural chance or the contingency of social circumstances The principles of justice are the result of a fair agreement or bargain This explains the propriety of the name “justice as fairness”: it conveys the idea that the principles of justice are agreed to in an initial situation that is fair.”—John Rawls, A Theory of Justice

Thus, one would develop rules for society from the “original position,” without knowing what your own position in society would be, without knowledge of one’s intellect (or lack thereof), physical ability (or disability), socioecomic status at birth, etc. The idea is that if we were to design a just society, we would want to do so in a way that, no matter what our circumstances in life, we would find the society to be fair. It is perhaps a naive idea, but an interesting way of approaching a controversial subject, like access to healthcare, for which it is extremely difficult to form an opinion.

My argument for universal access to healthcare is supported by reference to the “original position.” I have had the good fortune of having never lived in poverty or political chaos, having been blessed with a wonderful education, having always had a job when I wanted to work, and for many years a well-paying job with good benefits, including health insurance. I only know about the opposite situations through the opportunity of providing care to some patients who are much less fortunate, generally through no fault of their own, in which poverty, family dysfunction, loss of job, or other tragedy has left them in the position of being unable to have what I would consider adequate access to healthcare: not cosmetic surgery, or bariatric surgery, or in vitro fertilization, but rather treatment for basic medical problems.

If we were to design a healthcare system from scratch, putting ourselves in the original position, I am sure that we would want to be assured that no matter how we find ourselves years from now, we would be able to get and afford basic healthcare, regardless of whether we were mentally ill, unemployed, physically disabled, or impoverished.

I want to live in a society where, somehow, we arrange for this to happen. I start with the goal of universal access to healthcare as a First Principle, from which we then figure out how to make it work and how to pay for it.

I admit that this is very idealistic, perhaps naive, but I believe strongly that this is a valid way of approaching the idea of whether we should have universal access to healthcare.

Now I can go back to fishing in peace, when my mind is empty while casting for the beautiful trout which I can’t see in the bubbling water in front of me. Whether you agree with my ideas or not, I would be happy to take you fishing.

Dr. Brasington is professor of medicine and rheumatology fellowship program director at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine and an associate editor of The Rheumatologist.