Branko Devic / shutterstock.com

He just didn’t get it.

I love my mechanic. After many years of taking my car to mechanics who took my money without explaining what they were doing with it, I finally found someone who loved to teach. Whenever I bring my car to his shop, class is in session. He gestures for me to follow him into the garage and starts talking with an enthusiasm most men reserve for football. He delves into the bowels of my car and surfaces with damaged valves and frayed tubes, while excitedly explaining the pathogenesis of my automobile’s ailment.

That’s why I didn’t understand why he was being so obtuse.

My car had developed a coolant leak. At first, it was almost imperceptible. I thought it was due to insensible losses from a Baltimore summer. The car was otherwise working well, so I simply resigned myself to intermittently topping off the tank. When I realized I was stopping for coolant more often than I was stopping for gas, I knew it was time to bring my car in for a once-over.

My mechanic reassured me that an old hose was the likely culprit. One hose in particular abutted the engine, and the heat accelerated the aging of the rubber. Unfortunately, replacing the hose didn’t stop the leak, so I returned with my car a second time. My mechanic replaced another part, and I left with a full tank of coolant and instructions to return if the coolant warning light returned.

Three weeks later, I was back. This time, my mechanic emerged from the garage with a new suggestion. The source of the leak, obviously, was not obvious. Rather than continuing to fish blindly for the source, he suggested that we conduct a combustion pressure leakage test: Each cylinder would be connected, separately, to an instrument that would slowly apply increasing amounts of pressure until one of the cylinders confessed. Of course, this test would take time. He suggested that I take my car back and continue to top up the fluids until I could spare the car for three or four days.

But this time, I was prepared.

Since my last visit, I had taken to the internet. After some time, I was able to find a few blogs where others had described their experience with a mysterious coolant leak. They wrote with great certainty that when my mechanic said the words combustion pressure leakage test, I should instead ask him to use an all-purpose repair fluid. Apparently, the fluid consisted of graphite and solvents; the solvents would dissolve the sediment already in the engine, and recombine with the graphite to patch small leaks from the inside. I just needed a mechanic to inject the mixture directly into the engine.

At first, my mechanic looked puzzled. Then, he slowly explained to me that such miracle fluids had been on the market for decades. They sometimes helped, but the benefit was temporary. Worse, they could cause engine failure.

As I said, I love my mechanic. So I explained to him, patiently, that, from what I had read, engine failure was unlikely. In fact, many people on the internet reported that this approach worked when all others failed. Of course, I understood his reluctance to use a miracle fluid, since he stood to make much more money from his solution than from mine. Still, I was surprised that he barely glanced at the pages I had printed, which explained the procedure and the certainty of success.

As I left, he gave me a list of what he called reputable websites. He asked me to read about the procedure I had suggested on his websites, and to let me know if I had any questions. I thanked him for the information, but I couldn’t help but wonder if his lack of enthusiasm for my approach meant he had been duped by the auto industry.

Of course, this never happened.

The setup of this story is absolutely true; the difference is the denouement. After my mechanic told me he wanted to conduct a combustion pressure leakage test—whatever that was—I handed over my credit card so he would fix my car.

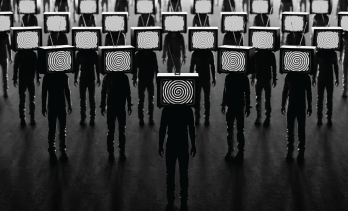

The idea that I would argue with my long-time mechanic over a car repair based on something I read off the internet probably strikes you as ludicrous. It would be like strolling into the cockpit of a 737 and telling the pilot, hold my beer. That said, versions of this conversation have been playing out in our clinics as our patients ask us to opine on why the medical industry refuses to acknowledge some easy fix for COVID-19.

The hydroxychloroquine imbroglio hit close to home because many of us have patients who lost access to this drug when the world became convinced it was the cure for COVID-19. After hydroxychloroquine fell out of favor, it was replaced by a parade of proposed remedies, including azathioprine, albuterol, antihistamines, aspirin, turmeric, hydrogen peroxide, famotidine, colloidal silver, even urophagia.1 Each of these proposed remedies was like a shooting star, burning bright, briefly, before fading into the dawn. Except for ivermectin. For some reason, hope in ivermectin persists. Ivermectin is like a zombie; just when you think it’s dead, it jumps out of the grave. Why does the ivermectin story endure?

Alternative Facts

First, it must be said—Merck doesn’t want your money. As you may know, Merck makes Stromectol, the brand-name version of ivermectin. Over a year ago, Merck posted the following message regarding the use of ivermectin for COVID-19 on its website:2

Company scientists continue to carefully examine the findings of all available and emerging studies of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 for evidence of efficacy and safety. It is important to note that, to date, our analysis has identified:

- No scientific basis for a potential therapeutic effect against COVID-19 from pre-clinical studies;

- No meaningful evidence for clinical activity or clinical efficacy in patients with COVID-19 disease, and;

- A concerning lack of safety data in the majority of studies.

We do not believe that the data available support the safety and efficacy of ivermectin beyond the doses and populations indicated in the regulatory agency-approved prescribing information.

Second—it must also be said—the story of ivermectin as a treatment for SARS-CoV-2 is incredibly difficult to follow, particularly if your main source of information is the lay press. Let me give you an example:

If you subscribed to The Wall Street Journal in July 2021, you might have happened across an opinion piece written by David R. Henderson and Charles L. Hooper. The piece is titled “Why is the FDA attacking a safe, effective drug?”