Branko Devic / shutterstock.com

He just didn’t get it.

I love my mechanic. After many years of taking my car to mechanics who took my money without explaining what they were doing with it, I finally found someone who loved to teach. Whenever I bring my car to his shop, class is in session. He gestures for me to follow him into the garage and starts talking with an enthusiasm most men reserve for football. He delves into the bowels of my car and surfaces with damaged valves and frayed tubes, while excitedly explaining the pathogenesis of my automobile’s ailment.

That’s why I didn’t understand why he was being so obtuse.

My car had developed a coolant leak. At first, it was almost imperceptible. I thought it was due to insensible losses from a Baltimore summer. The car was otherwise working well, so I simply resigned myself to intermittently topping off the tank. When I realized I was stopping for coolant more often than I was stopping for gas, I knew it was time to bring my car in for a once-over.

My mechanic reassured me that an old hose was the likely culprit. One hose in particular abutted the engine, and the heat accelerated the aging of the rubber. Unfortunately, replacing the hose didn’t stop the leak, so I returned with my car a second time. My mechanic replaced another part, and I left with a full tank of coolant and instructions to return if the coolant warning light returned.

Three weeks later, I was back. This time, my mechanic emerged from the garage with a new suggestion. The source of the leak, obviously, was not obvious. Rather than continuing to fish blindly for the source, he suggested that we conduct a combustion pressure leakage test: Each cylinder would be connected, separately, to an instrument that would slowly apply increasing amounts of pressure until one of the cylinders confessed. Of course, this test would take time. He suggested that I take my car back and continue to top up the fluids until I could spare the car for three or four days.

But this time, I was prepared.

Since my last visit, I had taken to the internet. After some time, I was able to find a few blogs where others had described their experience with a mysterious coolant leak. They wrote with great certainty that when my mechanic said the words combustion pressure leakage test, I should instead ask him to use an all-purpose repair fluid. Apparently, the fluid consisted of graphite and solvents; the solvents would dissolve the sediment already in the engine, and recombine with the graphite to patch small leaks from the inside. I just needed a mechanic to inject the mixture directly into the engine.

At first, my mechanic looked puzzled. Then, he slowly explained to me that such miracle fluids had been on the market for decades. They sometimes helped, but the benefit was temporary. Worse, they could cause engine failure.

As I said, I love my mechanic. So I explained to him, patiently, that, from what I had read, engine failure was unlikely. In fact, many people on the internet reported that this approach worked when all others failed. Of course, I understood his reluctance to use a miracle fluid, since he stood to make much more money from his solution than from mine. Still, I was surprised that he barely glanced at the pages I had printed, which explained the procedure and the certainty of success.

As I left, he gave me a list of what he called reputable websites. He asked me to read about the procedure I had suggested on his websites, and to let me know if I had any questions. I thanked him for the information, but I couldn’t help but wonder if his lack of enthusiasm for my approach meant he had been duped by the auto industry.

Of course, this never happened.

The setup of this story is absolutely true; the difference is the denouement. After my mechanic told me he wanted to conduct a combustion pressure leakage test—whatever that was—I handed over my credit card so he would fix my car.

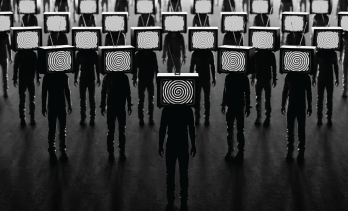

The idea that I would argue with my long-time mechanic over a car repair based on something I read off the internet probably strikes you as ludicrous. It would be like strolling into the cockpit of a 737 and telling the pilot, hold my beer. That said, versions of this conversation have been playing out in our clinics as our patients ask us to opine on why the medical industry refuses to acknowledge some easy fix for COVID-19.

The hydroxychloroquine imbroglio hit close to home because many of us have patients who lost access to this drug when the world became convinced it was the cure for COVID-19. After hydroxychloroquine fell out of favor, it was replaced by a parade of proposed remedies, including azathioprine, albuterol, antihistamines, aspirin, turmeric, hydrogen peroxide, famotidine, colloidal silver, even urophagia.1 Each of these proposed remedies was like a shooting star, burning bright, briefly, before fading into the dawn. Except for ivermectin. For some reason, hope in ivermectin persists. Ivermectin is like a zombie; just when you think it’s dead, it jumps out of the grave. Why does the ivermectin story endure?

Alternative Facts

First, it must be said—Merck doesn’t want your money. As you may know, Merck makes Stromectol, the brand-name version of ivermectin. Over a year ago, Merck posted the following message regarding the use of ivermectin for COVID-19 on its website:2

Company scientists continue to carefully examine the findings of all available and emerging studies of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 for evidence of efficacy and safety. It is important to note that, to date, our analysis has identified:

- No scientific basis for a potential therapeutic effect against COVID-19 from pre-clinical studies;

- No meaningful evidence for clinical activity or clinical efficacy in patients with COVID-19 disease, and;

- A concerning lack of safety data in the majority of studies.

We do not believe that the data available support the safety and efficacy of ivermectin beyond the doses and populations indicated in the regulatory agency-approved prescribing information.

Second—it must also be said—the story of ivermectin as a treatment for SARS-CoV-2 is incredibly difficult to follow, particularly if your main source of information is the lay press. Let me give you an example:

If you subscribed to The Wall Street Journal in July 2021, you might have happened across an opinion piece written by David R. Henderson and Charles L. Hooper. The piece is titled “Why is the FDA attacking a safe, effective drug?”

The subhead lays out the argument: “Ivermectin is a promising COVID treatment and prophylaxis, but the agency is denigrating it.”

In their article, the authors assert:3

The statistically significant evidence suggests that [ivermectin] is safe and works for both treating and preventing the disease. … Moreover, the drug can help prevent Covid-19. … If the FDA were driven by science and evidence, it would give an emergency-use authorization for ivermectin for COVID-19. Instead, the FDA asserts without evidence that ivermectin is dangerous.

If you had read this article in July 2021, you might have been left wondering—as have some of my patients—why physicians have been reluctant to recommend ivermectin to treat COVID-19. I don’t think of the average reader of The Wall Street Journal as a firebrand. That said, the online version of the article received 1,430 comments, many of which asserted the FDA response had been engineered by vaccine manufacturers seeking to enhance their profits.

In the byline, the article referenced the lead author’s affiliation with the Hoover Institution, “a public policy think tank that seeks to improve the human condition by advancing ideas that promote economic opportunity and prosperity, while securing and safeguarding peace for America and all mankind.”4 The article seems beyond reproach. Indeed, you would have to do quite a bit of homework to figure out that most of the article is misleading—or just plain wrong.

For example, only the most loyal readers of The Wall Street Journal probably noticed that two days after the article appeared, the authors published an erratum:

We, the authors … have egg on our faces. Relying on a summary of studies published in the American Journal of Therapeutics, we quoted the results from a study of 200 healthcare workers. After our article was published, we learned that this study, by Ahmed Elgazzar of Benha University in Egypt, has recently been retracted due to serious charges of data manipulation.

Perhaps the authors shouldn’t have felt too bad. On the one hand, Hoover Institute research fellows should have known better than to cite data from a review article without reviewing the original article—the academic equivalent of citing Wikipedia as a reference. That said, the claims made by Elgazzar’s group were dramatic: 94% of patients with severe COVID-19 improved after only four days of treatment with intravenous ivermectin, which was associated with a 10-fold improvement in mortality. Moreover, prophylactic treatment with ivermectin decreased the rate of transmission to close contacts from 10% to 2%.5

The results of the study were so impressive that, in preprint form, it was widely referenced by those who argued that vaccination was not the only way out of the pandemic. All told, the preprint was eventually cited by four meta-analyses and 20 scientific publications, in addition to The Wall Street Journal article.6

Had Henderson and Hooper read Elgazzar’s article for themselves, they might have picked up on the oddly stilted writing. Apparently, the non-idiomatic phrasing was due to the authors’ liberal use of a thesaurus to replace keywords, to obscure the fact that their introduction was largely lifted from websites and press releases. Severe acute respiratory syndrome, for example, became extreme intense respiratory syndrome.

With a little more digging, Henderson and Hooper might have noticed even more discrepancies:7

- The raw data included three children, although the article claimed to have studied only adults;

- The raw data recorded patient deaths that had not been reported in the final paper; and

- The raw data indicated that most of the deaths included in the study analysis occurred before the first subject had been enrolled.

All of these issues were noticed by Jack Lawrence, a student in the biomedical science program at St. George’s University of London, who read the article for a class he was taking. Further sleuthing revealed that numerous subjects in the control group had been cloned. Approximately 80 patients had their data entered more than once; the entries had been duplicated, down to the patient’s initials and typographical errors.8 Both Mr. Lawrence and The Guardian contacted Research Square, the company that hosted the preprint, regarding their concerns; the next day, the preprint was withdrawn.9

I, personally, have patients who have refused coronavirus vaccination based, in part, on their faith in ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine & other pipe dreams. It is truly sobering to think how many deaths during this pandemic may be attributable to fraudulent studies.

By that time, unfortunately, the damage had been done. The fraudulent study was so large and the findings so significant that it overwhelmed every analysis that included it. Even now, many articles, such as the original opinion piece that appeared in The Wall Street Journal, reference Elgazzar’s paper as proof of ivermectin’s promise. These articles, in turn, have influenced policy makers and public forums, much to our detriment.

The Ivermectin Experience

Elgazzar’s study is not the only one that supported the use of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19. That said, many other ivermectin studies have also been tainted by allegations of fraud.

One large study from Lebanon was retracted after it was found that the analysis was based, accidentally, on a test data set, comprising information from the same seven patients repeated numerous times. Other large studies from Iran and Italy have demonstrated inconsistencies indicating a lack of randomization. A study from Brazil was called into question when one of the hospitals listed as a study site reported that it had not participated in the trial.10

A review of 26 randomized controlled trials examining the use of ivermectin for COVID-19 found that 10 had obvious evidence of fraud (e.g., identical data used for multiple patients, evidence of non-random treatment allocation, mathematical errors or lack of approval by local regulatory agencies). Approximately half of the studies refused to share their raw data for independent review.11

Fame and fortune are the obvious motivations for committing fraud. Last year, a joke regarding a manuscript submitted to a journal for publication was circulating on the internet: the article had failed to include the words SARS, coronavirus or COVID; because this was an obvious oversight, the article was being returned immediately to the authors for revision. Particularly early in the pandemic, when we knew nothing, I think it’s safe to say that the threshold for publishing an article on SARS-CoV-2 was lower than usual. Because faking a 500-subject study is not 10 times harder than faking a 50-subject study, the temptation to commit fraud was likely too great for some.

The ivermectin experience has called into question how meta-analyses are conducted. It is standard practice to conduct a meta-analysis based on summary data alone. Given the dubious quality of many ivermectin studies, future meta-analyses may require a review of individual patient data from each included study to protect such analyses from using falsified information.12

Such data reviews may become standard for primary research articles as well. The peer review process was never designed to identify fraud. The ivermectin experience shows us this needs to change. In the future, requiring all clinical trials to submit their raw data for statistical analysis prior to publication will likely become standard.

More broadly speaking, the ivermectin experience has also demonstrated the importance of ethics training for physicians and for anyone involved in the conduct of clinical trials. As someone who has doodled his way through more lectures on autonomy, beneficence and justice than he can count, I am the last person to suggest another mandatory module. Instead, I hope someone takes the ivermectin experience as impetus to create a new approach to teaching medical ethics that highlights how fraudulent research has impacted all of our lives.

I personally have patients who have refused coronavirus vaccination based, in part, on their faith in ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine and other pipe dreams. It is truly sobering to think how many deaths during this pandemic may be attributable to fraudulent studies.

Publishers, academic institutions and professional societies need to ensure that punitive penalties are attached to fraudulent research, beyond the usual effete gnashing of teeth. Policing our colleagues’ work is always uncomfortable, but throughout the pandemic, we have asked for our patients’ trust; now, we need to make certain that we have earned it.

Philip Seo, MD, MHS, is an associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is director of both the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center and the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Fellowship Program.

Philip Seo, MD, MHS, is an associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. He is director of both the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center and the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Fellowship Program.

References

- Lee BY. ‘Vaccine police’ founder claims drinking urine is COVID-19 antidote. Forbes. 2022 Jan 10.

- Merck statement on ivermectin use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Merck. 2021 Feb 4.

- Henderson DR, Hooper CL. Why is the FDA attacking a safe, effective drug? The Wall Street Journal. 2021 Jul 28.

- About Hoover. Hoover Institution.

- Elgazzar AG, Hany B, Yousssaf SMA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ivermectin for treatment and prophylaxis of COVID-19 pandemic [withdrawn]. Research Square.

- El-Gazzar AG, Hany B, Yousssaf SMA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ivermectin for treatment and prophylaxis of COVID-19 pandemic. Scite. 2020.

- Davey M. Huge study supporting ivermectin as COVID treatment withdrawn over ethical concerns. The Guardian. 2021 Jul 15.

- Brown N. Some problems in the dataset of a large study of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19. Nick Brown’s blog. 2021 Jul 15.

- Lawrence J. Why was a major study on ivermectin for COVID-19 just retracted? Grftr. 2021 Jul 15.

- Piper K. How bad research clouded our understanding of COVID-19. Vox. 2021 Dec 17.

- Schraer R, Goodman J. Ivermectin: How false science created a COVID ‘miracle’ drug. BBC. 2021 Oct 6.

- Lawrence J M, Meyerowitz-Katz G, Heathers JAJ, et al. The lesson of ivermectin: Meta-analyses based on summary data alone are inherently unreliable. Nature Medicine. 2021 Sep;27:1853–1854.