ARTFULLY PHOTOGRAPHER/shutterstock.com

WASHINGTON, D.C.—In the next 15 years, it will be increasingly difficult to provide adequate care for rising numbers of patients with rheumatic diseases due to a severe shortage of trained rheumatology healthcare providers, according to the ACR’s 2015 Workforce Study of Rheumatology Specialists in the United States.

The full study is available online, and panelists from private practice and academic centers led a discussion on the study’s findings and ideas to address workforce shortages at a Nov. 14, 2016, session, The Rheumatology Workforce: Present and Future, at the 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

“By 2025, the U.S. will face a shortage of physicians. Of course, this will impact primary care a lot, but in some cases, the rheumatologist is the primary care provider for our patients,” said Daniel F. Battafarano, DO, MACP, FACR, a rheumatologist at San Antonio Military Medical Center in Texas, and co-chair of the Workforce Study Group with Seetha U. Monrad, MD, at the University of Michigan. The new ACR workforce data mirror what other subspecialties of medicine face today, he said.

Numbers Reveal a Crisis

This is the first major rheumatology workforce analysis since the ACR’s 2005 study, Dr. Battafarano said.1 It used an integrated model that combined supply and demand–based methodologies, socioeconomic factors driving patient demand, epidemiological factors that drive healthcare needs, existing training processes and healthcare utilization rates. Electronic surveys of ACR and ARHP members measured patient workload and demographics.

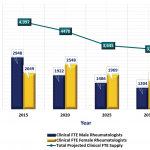

Not every rheumatologist sees the same number of patients each week, so the study group adjusted gross numbers of providers to calculate the number of clinical full-time equivalents (FTE) available to treat patients. Based on average clinical workload, a rheumatologist in private practice was measured as one clinical FTE, while someone working in an academic setting was measured as 0.5 FTE. The study assumed that 80% of the current adult U.S. rheumatology workforce is in private practice and 95% of pediatric workforce is in an academic setting. The clinical FTE for academic pediatric rheumatologists may be significantly underestimated at 0.5 clinical FTE, and this warrants further analysis.

The 2015 study estimated both NPs and PAs in the current workforce, and these providers counted as 0.8 clinical FTE. Currently, about 5% of all NPs and 1.9% of all PAs work in rheumatology, the study found.

Patient demand, or U.S. adults with doctor-diagnosed arthritis, is projected to rise from 52.5 million in 2012 to 67 million by 2030, according to the study.

“In the past, we were able to get a good head count of board-certified rheumatologists, but they weren’t all full-time, practicing clinical physicians, and some were retired or in industry,” said Dr. Battafarano. “Also, as people plan to retire, they start to decrease their patient workload in their last five to 10 years before retirement. So we have incremental part-time employment before rheumatology providers actually retire.”