ATLANTA—A 7-year-old girl presented to her pediatrician with a fever, nausea, vomiting and a headache, and was diagnosed with a sinus infection. As her symptoms grew worse and more complex, the case led neurologists and rheumatologists on a long hunt for a diagnosis—ultimately, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (anti-MOG) autoimmune encephalomyelitis—that highlighted how patience, a thorough workup and multi-department teamwork can be crucial for proper diagnosis and management of a pediatric patient with inflammatory brain disease.

ATLANTA—A 7-year-old girl presented to her pediatrician with a fever, nausea, vomiting and a headache, and was diagnosed with a sinus infection. As her symptoms grew worse and more complex, the case led neurologists and rheumatologists on a long hunt for a diagnosis—ultimately, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (anti-MOG) autoimmune encephalomyelitis—that highlighted how patience, a thorough workup and multi-department teamwork can be crucial for proper diagnosis and management of a pediatric patient with inflammatory brain disease.

A discussion of the case and its lessons was led at the 2019 ACR/ARP Annual Meeting by Elizabeth Wells, MD, director of inpatient neurology at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, D.C., and Heather Van Mater, MD, MSc, a pediatric rheumatologist at Duke Children’s Hospital, Durham, N.C.

Initial Diagnosis

After the sinus infection diagnosis, the girl’s headache got worse and she had difficulty using her hand, prompting an emergency department visit. She was found to have sinusitis on a computerized tomography scan, with a white blood count (WBC) of 12.5 and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 1.6. With a severe headache, a moody disposition and sleepiness at Day 12, she was referred to neurology.

“The biggest things for me as a neurologist at this point would be that focal complaint—that her right hand was not working at some point—as well as the fact that the headache is severe, persistent and not getting better—and that it was her first headache,” with no history of headache or migraine, Dr. Wells said.

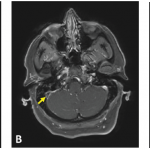

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed sphenoid sinusitis with T2 changes in the frontal lobe. Because of the migraine, she was given prednisone for five days on day 17. Her symptoms resolved, but after the steroids were stopped she again developed a headache and a low-grade fever, with excessive sleepiness and irritability.

She was admitted to the hospital on the 25th day, still with a presumed migraine. She had a CRP of 11.7, WBC of 34.9 and hemoglobin of 12.9. She was treated for migraine, released with an oral steroid taper and improved at home.

Signs of a Deeper Problem Missed

Dr. Wells said signs of a deeper problem were missed early on.

“There may have been some anchoring bias here, where she got diagnosed with migraine and then was getting better, but I still think back to those focal symptoms she had initially,” as well as her abnormal lab findings, Dr. Wells said.

A few days later, things got much worse. The girl had hallucinations and a seizure that became status epilepticus, with a WBC of 34.8, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 36 and a CRP of 11.2. A lumbar puncture found a WBC of 211 with a segmented neutrophil reading of 81% and red blood cell count of zero.