Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a systemic autoimmune disease in which immune-mediated inflammation causes secretory gland dysfunction, leading to dryness of the main mucosal surfaces and systemic organ involvement.1 The disease has a difficult-to-pronounce name due to the Swedish ophthalmologist Henrik Sjögren (1899–1986), who described the main disease characteristics in his 1933 doctoral thesis “Zur Kenntnis der keratoconjunctivitis sicca.” The cause of SS is unknown, but genetic and environmental factors seem to play a role. When symptoms appear in a previously healthy person, the disease is classified as primary SS (pSS). When sicca features are found in association with another systemic autoimmune disease, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic sclerosis (SSc), or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), it is classified as associated SS; pSS may also be associated with various organ-specific autoimmune diseases.

SS primarily affects white perimenopausal women, with a female:male ratio of nearly 20:1. The disease may occur at all ages, but typically has its onset in the fourth to sixth decades of life. An estimated 2–4 million people in the U.S. have SS, of whom approximately 1 million have an established diagnosis.2 Recent studies using the best-accepted classification criteria (2002 American-European) have estimated a prevalence of one to nine cases per 10,000 people (0.01–0.09%) and an annual incidence of 4.2 cases/100,000 people in the U.S.3 A differentiated clinical and immunological expression has been reported for specific epidemiological subsets (males, pediatric and elderly patients).

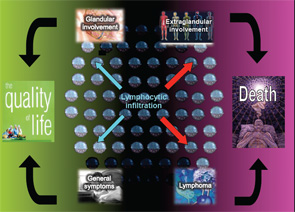

The autoimmune origin of sicca syndrome is often confirmed by positivity for circulating autoantibodies, although some laboratory abnormalities may support the clinical suspicion of pSS, including normocytic anemia, mild leukopenia and, especially, high serum gammaglobulin levels and a markedly raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The variability in the presentation of SS may partially explain delays in diagnosis of up to 10 years from the onset of symptoms. On the one hand, SS is a disease that can be expressed in many guises depending on the specific epidemiological, clinical or immunologic features. On the other hand, SS may be a serious disease with an excess of mortality mainly related to systemic involvement and B-cell lymphoma (see Figure 1). The health costs of SS are significant and similar to those of RA—more than double the cost of non-autoimmune primary care patients.1

Clinical Presentation: More Than Sicca Features

SS may be expressed in many guises, and there are three predominant clinical presentations at onset.1