The definition of pruritus, more commonly known as itch, was introduced by a German physician named Samuel Hafenreffer in 1660 as an “unpleasant sensation that elicits the desire or reflex to scratch.”1 Chronic pruritus affects approximately 15–20% of the U.S. population and accounts for more than 7 million outpatient visits per year in the U.S.2 In addition to its high prevalence, chronic pruritus affects multiple quality of life (QoL) parameters, including mood, concentration, eating habits, sexual function and sleep.3-5 Indeed, QoL studies have shown equivalence in terms of impact of chronic pain and chronic itch on QoL measures.6

Despite the high burden of itch-associated conditions on both society and the individual, itch as a medical problem remains an overlooked epidemic because the etiology of itch remains poorly understood. Even 354 years after Hafenreffer initially defined pruritus, treatments remain limited, with no FDA-approved medications for use in humans.

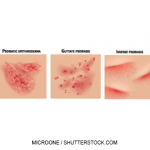

It’s widely appreciated that chronic pruritus underlies multiple dermatologic conditions, such as atopic dermatitis (AD), contact dermatitis and psoriasis. Beyond the skin, pruritus is associated with a variety of systemic medical conditions, including, but not limited to, chronic kidney disease (CKD), liver dysfunction, malignancy, various infections and even psychiatric disease (see Table 1). Recent scientific advances have revealed previously unrecognized itch-specific pathways that are regulated by particular mediators, including neurotransmitters, pharmacologic agents and inflammatory cytokines (see Figure 1).7,8 Although off-label treatments can be employed, more investigation is needed to develop definitive therapeutics to appropriately target chronic pruritus. Recent scientific discoveries have led to a greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying the sensation of itch, which will invariably inform the design of novel treatments in the future.

Pathophysiology of Itch

Classically, itch was viewed as a mild form of pain. As a result, the prevailing wisdom was that the same neurologic pathways mediated both pain and itch. The identification of histamine-responsive neurons in the periphery revealed for the first time that distinct itch-sensitive, pain-independent pathways were present.9,10 However, it was widely appreciated that antihistamines, although effective in certain forms of itch (e.g., urticaria-associated itch), were ineffective in the treatment of many forms of chronic pruritus. These clinical observations provoked the hypothesis that perhaps histamine-independent pathways were present.

Acute itch, as seen in response to arthropod bites & poison ivy, is transient in nature. In contrast, chronic itch is highly debilitating & its etiology is often difficult to define.

Indeed, in 2009 Liu et al identified the Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor (Mrgpr) as a novel family of histamine-independent itch receptors expressed in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG).11 Subtypes of Mrgprs have been identified in both mice and humans.12 Further, MrgprA3 is activated by the drug chloroquine, which has been associated with the development of itch in patients.11 Beyond the peripheral nervous system (PNS), Sun et al identified the first receptor that mediates itch in the central nervous system (CNS), namely gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR).13 This seminal discovery identified that itch can be regulated both in the periphery, where exogenous pruritogenic stimuli may be encountered, as well as centrally in the spinal cord itself.