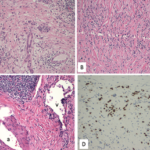

Figure 1

Retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF) is a rare condition characterized by aberrant fibroinflammatory tissue developing in the retroperitoneum. This disorder was initially called Ormond’s disease. RPF may be idiopathic or secondary to other conditions. Idiopathic RPF is a part of the disease spectrum of chronic periaortitis due to its typical periaortoiliac localization.

Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis is a relatively uncommon condition characterized by chronic fibroinflammatory proliferation in the retroperitoneum, usually around the infrarenal abdominal aorta and iliac vessels.1,2 It can lead to compression of retroperitoneal structures and a myriad of associated complications, most commonly obstructive uropathy and acute renal injury that can progress to end-stage renal disease.1,2,3

Due to its nonspecific and atypical clinical manifestations, prompt and early diagnosis can be challenging. Prognosis is mainly determined by the impact on renal function and complications from systemic corticosteroids.2

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old Black woman presented to the hospital complaining of nausea, decreased oral intake, diffuse abdominal pain and profuse watery diarrhea, all of which had persisted over a few weeks. She was found to have severe acute kidney injury with a serum creatinine of 9.3 mg/dL. Her baseline serum creatinine had been between 0.7 mg/dL and 0.8 mg/dL in prior years. She did not have a history of abdominal surgery or a family history of renal, oncologic or rheumatic conditions. She had never smoked cigarettes, although she had smoked cannabis for years. A urinalysis did not demonstrate evidence of an active sediment.

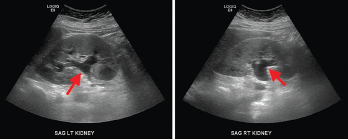

A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated mild symmetric prominence of the renal pelvises (see Figure 1, top), which was thought to be an incidental finding. A renal ultrasound showed mild bilateral hydronephrosis (see Figure 2, bottom) but the kidneys were found to be of normal size and echogenicity. An evaluation by a nephrologist and a gastroenterologist led to the conclusion that she likely had suffered severe gastrointestinal fluid losses, possibly due to gastroenteritis, which in turn led to acute tubular injury due to severe dehydration.

Figure 2. Renal ultrasound, sagittal view, showing mild bilateral hydronephrosis (arrows) with expansion of the renal sinus and calyces with normal renal cortical thickness and echogenicity.

The patient was treated with intravenous hydration and supportive care. Her serum creatinine declined to 1.9 mg/dL, and her gastrointestinal symptoms had resolved by the time of discharge. During this hospitalization, she had also been diagnosed with right-sided Bell’s palsy, for which she received a one-week course of prednisone and valacyclovir. She was also diagnosed with hypertension, which was treated with amlodipine.

A month later, the patient was seen for follow-up by her primary care provider. Laboratory studies showed her serum creatinine level had increased to 5.96 mg/dL; she was asked to return to the hospital for further evaluation. At the time of this second admission, she noted two weeks of fatigue, generalized weakness and constant bilateral flank pain. She had intermittently loose stools but no recurrence of severe abdominal pain or diarrhea. She did not have urinary symptoms or hematuria, and she was not taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or supplements.

The patient’s physical examination was significant for hypertension, tachycardia and non-pitting edema of the left leg. The abdomen was soft, without tenderness or guarding. There was no costovertebral angle tenderness.

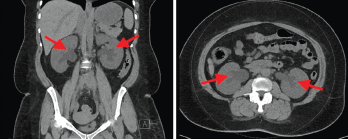

Laboratory findings demonstrated a blood urea nitrogen of 49 mg/dL and a serum creatinine of 11.1 mg/dL. Her urinalysis was unremarkable. A non-contrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a retroperitoneal density around the aortic bifurcation. Pelvic masses and mesenteric adenopathy were not seen (see Figure 3). A renal ultrasound (see Figure 4) showed grade 2 bilateral hydronephrosis. A lower extremity ultrasound did not demonstrate evidence of deep venous thrombosis.