Small fiber neuropathy is a common form of peripheral neuropathy with multiple potential etiologies and a varied clinical presentation. It can’t be detected by nerve conduction studies, making it an elusive and often overlooked entity. Small fiber neuropathy is well documented in several rheumatic diseases, and its symptom burden can profoundly affect quality of life. Thus, rheumatologists should have the knowledge to suspect and evaluate for this condition in the clinic.1

Small fiber neuropathy is a common form of peripheral neuropathy with multiple potential etiologies and a varied clinical presentation. It can’t be detected by nerve conduction studies, making it an elusive and often overlooked entity. Small fiber neuropathy is well documented in several rheumatic diseases, and its symptom burden can profoundly affect quality of life. Thus, rheumatologists should have the knowledge to suspect and evaluate for this condition in the clinic.1

In this article, we speak with Michael Polydefkis, MD, associate professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he collaborates with the Jerome L. Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Center and has a particular interest in peripheral neuropathy. His expertise is in nerve conduction studies, electromyography, and nerve, skin and muscle biopsy. He shares his practical approach to the diagnosis and management of small fiber neuropathy with an emphasis on essential knowledge for both the community and academic rheumatologist.

Background

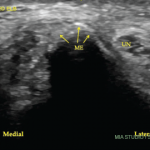

Peripheral nerve fibers can be broadly classified by nerve fiber diameter as small or large. Small fiber neuropathy is due to the destruction of the smaller, lightly myelinated A-delta and unmyelinated C fibers.2 Small fibers, the largest subset of peripheral nerves, include nociceptors and autonomic fibers. Damage to these often results in positive symptoms, such as pain, paresthesia (i.e., a burning or prickling sensation) and allodynia (i.e., extreme sensitivity to touch; pain due to a stimulus that does not normally provoke pain).

Large fibers, on the other hand, represent a smaller subset of peripheral nerves and, when dysfunctional, lead to negative symptoms, such as loss of proprioception and vibration sense, diminished ankle reflexes and numbness. Dr. Polydefkis points out that “large fibers also innervate muscles and, therefore, can be associated with weakness when injured.”

Most neuropathies, such as diabetic neuropathy, involve dysfunction of both small and large fibers. Dr. Polydefkis says “in many instances, small fibers are affected first, and patients then develop large fiber involvement with time,” as occurs in diabetes.

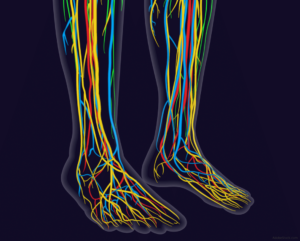

Length dependence is an essential concept to be cognizant of when evaluating for neuropathy. When a neuropathy presents in a length-dependent manner, it first appears in the nerves of the greatest length, such as at the toes, and then progresses proximally up the lower extremities, with eventual involvement of the hands and upper extremities. This is the classic pattern of a diabetic- or alcohol-related neuropathy. Small fiber neuropathy, however, can be non-length dependent,and proximal regions may be affected first, with patchy involvement that does not map onto a particular sensory nerve distribution.2