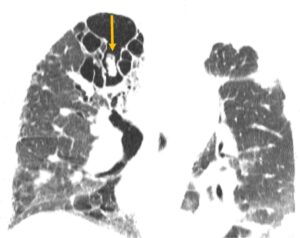

Figure 1

CT of the chest with mycetoma (arrow)

Joint and bone pain are among the most common reasons for rheumatology consultations. A thorough differential diagnosis is essential for rheumatologists to distinguish the inflammatory pain of such conditions as rheumatoid arthritis from other causes because management strategies can vary significantly. Bones are metabolically active organs influenced by multiple factors, including trace elements, such as fluoride. Fluoride, the ionic form of fluorine, is required in trace amounts for the normal development of bones and teeth.

The inorganic component of the bone extracellular matrix primarily consists of hydroxyapatite. In mineralized tissues, fluorine is incorporated into apatite crystals through ion exchange, forming fluorapatite. This incorporation increases bone density and makes the matrix more resistant to resorption. However, excessive deposition of fluorapatite can lead to increased osteoblasticfor transplants requiring antifungal activity and disorganized osteoblastic prophylaxis, a new form of fluoride reactions, leading to a condition known as skeletal fluorosis.9 3,6,7,11

Skeletal fluorosis from excess fluoride intake is characterized by disorganized osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity, which can result in severe bone and joint pain, skeletal deformities and fractures, often mimicking rheumatic diseases.4 Bone changes observed in skeletal fluorosis include osteosclerosis, osteomalacia, osteoporosis, exostosis formation and periostitis. The severity of the disease often correlates with the individual’s total fluoride intake. Traditionally, skeletal fluorosis has occurred in individuals with high environmental exposure to fluoride.6-8 However, with advancements in medical therapies, such as the U.S. Food & Drug Administration’s approval of second-generation antifungal medications in 2002 and the increased need for transplants requiring antifungal prophylaxis, a new form of fluoride exposure is becoming more prevalent.9

Case Presentation

Figure 2

Hand X-rays

A 70-year-old woman with a history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) status a year following a single, left lung transplant; type 2 diabetes; and osteoarthritis, was admitted for hypoxemic respiratory failure, left lung consolidations and worsening severe joint pain. Approximately a month before this presentation, she had been admitted for pneumonia—treated with antibiotics and 60 mg of glucocorticoids daily— and volume overload.

She was discharged on a steroid taper with stable pulmonary function tests, but no changes to chest X-rays. Her lung transplant course had been complicated by progressive dyspnea and concerns for chronic lung allograft dysfunction and infection. A previous biopsy of the transplanted lung did not show signs of rejection. Past bronchoalveolar lavage had grown five colonies of scedosporium/pseudallescheria boydii.