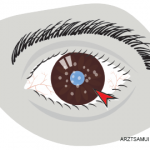

In scleritis, a rarer condition, almost 60% of cases are due to underlying systemic associations. Rheumatologists must consider scleritis as a possible complication of RA, SLE, ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and Sjögren’s syndrome. Diagnosis includes tactile stimulation resulting in increased pain sensation, and therapies may include systemic corticosteroids and potentially steroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapy depending upon the severity of disease and chronicity of ocular inflammation.

There are some cases of masquerading syndromes that appear to be inflammatory eye disease but are not, Dr. Papaliodis said. Some conditions that can mimic intraocular inflammation include malignancy and ocular infections, he said.

Collaborating with Colleagues

Although rheumatologists are comfortable diagnosing systemic diseases, they may be uncomfortable evaluating the eyes of their patients, said Sergio Schwartzman, MD, associate attending rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. “I believe this is an area where there should be a very close marriage between the rheumatologist and the ophthalmologist, or else patients will suffer,” he stressed.

To diagnose uveitis, a thorough medical history and physical examination, including a slitlamp exam, are most important, Dr. Schwartzman said. An ophthalmologist with experience in treating autoimmune eye diseases should also participate in these patients’ care, he added. Rheumatologists should, at minimum, test for syphilis and tuberculosis, conduct a baseline chest X-ray and routine laboratory tests, and evaluate the patient for Lyme disease. Further testing would be based on the patient’s history and physical exam, he said.

Rheumatologists have various challenges in treating their patients who present with these conditions, Dr. Schwartzman said. It is likely that studies of various therapies in autoimmune eye diseases are limited by low patient numbers and trial design. Many ophthalmologists treat uveitis with prolonged corticosteroid therapy, but there is some early evidence to support use of immunosuppressive and remittive medications earlier, he said. In a condition like acute anterior uveitis, which is rarely seen by rheumatologists except in patients with spondylarthropathies, topical steroid drops typically treat the uveitis successfully.

Remittive medications used to treat recalcitrant or “resistant” uveitis include methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and, rarely, cyclophosphamide. There are few prospective, randomized studies on these therapies and even fewer head-to-head trials, he said. The First-line Antimetabolites as Steroid-sparing Treatment uveitis pilot trial (FAST) was designed to compare oral mycophenolate mofetil with oral methotrexate in uveitis patients who needed corticosteroid-sparing therapy. Results are not yet published.

Other options for treating uveitis include intraocular drug delivery methods such as implants, which bypass the ocular barrier and have become increasingly successful. However, as these are corticosteroid implants, glaucoma and cataracts are possible complications, he noted.