Can a heart involved with amyloid tolerate the immunologic chaos that might occur when you’re directing antibody attack on a major organ?

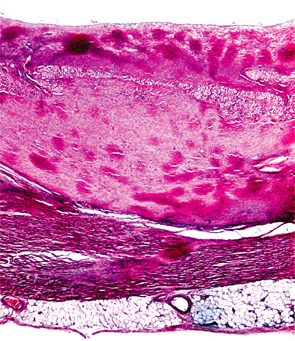

Image Credit: Biophoto Associates/Science Source

SAN FRANCISCO—Treatment for transthyretin-related amyloidosis (ATTR) is generating more interest from academic researchers and the pharmaceutical industry, with encouraging early results using a multi-pronged therapeutic approach, a researcher said at a review course held before the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

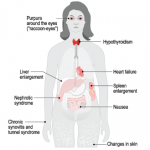

Amyloidoses are a rare and potentially deadly family of diseases in which misfolded protein builds up in organs, with symptoms that often make themselves known only after the disease has progressed significantly. It comes in the form of primary amyloidosis, stemming from abnormal plasma cells; secondary amyloidosis, derived from the inflammatory protein serum amyloid A; and familial forms.

Only about 3,000–4,000 cases of primary amyloidosis, the most common form, are seen in the U.S. each year, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

ATTR, the most common type of hereditary amyloidosis, is even more rare, with only about 10,000 people affected worldwide. The disease involves protein deposits to the nerves, GI tract, heart and eyes, with a median survival of 5–15 years.

“TTR represents 10 to 20% of amyloid seen in the U.S. and Europe,” said presenter John Berk, MD, clinical director of the Amyloid Center at Boston University School of Medicine. “Impressively, over the past 10 years, industry has [spent], and will spend, more than $600 million on clinical trials for drug development in ATTR. And that’s the result of their investigational products being preferentially delivered to the liver where the amyloidogenic TTR protein is generated.”

The TTR protein normally transports thyroid hormone and vitamin A, but people with mutations in the TTR gene produce variants of the protein throughout their lives, causing formation of amyloid fibrils.

It’s been about two years since Dr. Berk led a trial on an unlikely candidate for ATTR treatment: the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diflunisal.

Diflunisal in Studies

Diflunisal has been found to stabilize transthyretin tetramers and prevent amyloid fibril formation in vitro. In the trial, researchers randomized 130 patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy, featuring progressive peripheral nerve deficits and disability.1 Half were assigned to get 250 mg of diflunisal twice a day for two years, and half were assigned to placebo.

There was a high level of dropout in the study, mainly because of disease progression and ready access to the active drug outside the study, according to Dr. Berk.