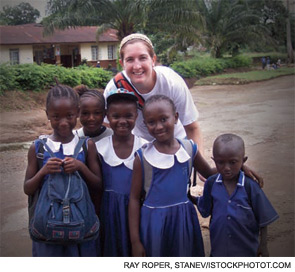

In October 2009, the two of us—an adult rheumatologist and a pediatric rheumatologist, both lupus researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston—embarked on a trip to western Africa. Our initial interest in going to the Republic of Sierra Leone stemmed from research that is currently underway at MUSC involving a special group of people, the African American Gullah community. We wanted to go to the home of the Gullahs in Africa to explore an important issue in the study of lupus—the relationship between genes and environment in pathogenesis. Although our trip made us think differently about lupus, its impact was far greater, giving us a lasting and sobering view of the obstacles of global research and, more importantly, global healthcare. The longer we were there, the more the purpose of the trip changed.

Sierra Leone was a center for transatlantic human trade until 1792, when Freetown, Sierra Leone’s capital, was founded by the Sierra Leone Company as a home for formerly enslaved African Americans. The Gullah people, who currently inhabit the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia, are direct descendents of the slaves who labored on the rice plantations, and their language reflects significant influences from Sierra Leone. The connection between the Gullah people and the people of Sierra Leone is a very special one. The rice plantation zone of coastal South Carolina and Georgia was the only place in the Americas where Sierra Leonean slaves came together in a large enough number and over a long enough period of time to leave a significant linguistic and cultural impact. The people of Sierra Leone look to the Gullah of South Carolina and Georgia as a kindred people sharing many common elements of speech, custom, culture, and cuisine.1

The investigative team at MUSC is currently studying lupus in African Americans from the Sea Island communities of South Carolina and Georgia. The main purpose of the study is to identify and characterize genes as well as factors from the environment that result in the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. The initial findings from the study revealed that lupus in the African American Gullah community is similar in its presentation to that in other African American populations. However, familial prevalence is twice that of other African American cohorts, suggesting a prominent genetic influence on overall disease. In contrast to the situation in the Sea Island communities, lupus is reportedly rare in West Africa where the Gullah originated. The question thus arose as to whether this prevalence gradient results from underdiagnosis of lupus in Africa or the presence of environmental factors in the United States that play a strong role in promoting the expression of this disease. Genetically, the Gullah are very similar to West Africans, with minimal Caucasian or Native American admixture, suggesting that differences in lupus prevalence between the regions is unlikely genetic in origin.

Health Dangers, War Aftereffects

Darius Maggi, MD, a retired obstetrician/gynecologist from Texas, began traveling to Sierra Leone seven years ago to provide medical care to repair obstetric fistulas. He shortly thereafter set up an organization called the West Africa Fistula Foundation that works to improve the lives of women with obstetric fistulas. According to the foundation, in Sierra Leone, one in eight women die during childbirth and, throughout Africa, two to three million women suffer from obstetric fistulas as a result of labor complications. There are very few, if any, Caesarian sections, and many women labor in their villages for days. This situation is improving in most of West Africa, but not in Sierra Leone. Dr. Maggi invited us to travel to Sierra Leone during one of his trips to the region so we could obtain serum and screen for lupus in the Sierra Leonian women seen at the Bo Government Hospital.

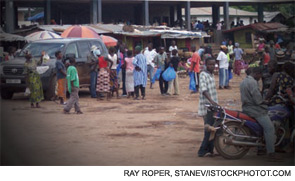

Sierra Leone is a country in West Africa similar in size and population to the state of South Carolina. The two largest ethnic groups are the Mende and Temne tribes. English is the official language, and Krio is a language derived from English and several African languages and native to the Sierra Leone people. Krio is widely spoken in all parts of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone is most widely known in this country for the brutal civil war that began in 1991 and officially ended in 2002, as is depicted in the movie “Blood Diamond,” which took place in Bo. The people of Sierra Leone suffered greatly during this war, which enlisted boy soldiers as combatants and resulted in thousands of deaths and limb mutilations. Each Sierra Leonian has a unique and frightening war story. The war was devastating, especially in Bo.