WASHINGTON, D.C.—New and potentially vital insights into the factors that lead to bone erosion and formation could point the way to new treatments for the terrible effects that arthritic conditions can have on bone, an expert on the subject said during the Rheumatology Research Foundation’s Oscar S. Gluck, MD, Memorial Lectureship, “Bone Wasn’t Built in a Day,” at the 2012 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held November 9–14.

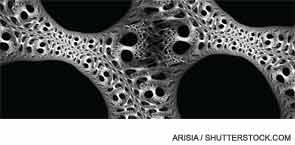

With forces vying for bone destruction and for bone creation, the healthy outcome is a draw between the two—but that often doesn’t happen in those with arthritic conditions, said Ellen Gravallese, MD, professor of medicine and cell biology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Boston.

The result is bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and debilitating bone formation in conditions like ankylosing spondylitis. “Ultimately, there’s a balance between osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and osteoblast mediated bone formation,” Dr. Gravallese said. “And the question is, How is this balance maintained?”

Figuring out this process—and how it’s undermined in those with arthritic diseases—is a problem being tackled in laboratories throughout the world.

Reviewing Some Findings

Studies have found that bone edema is a sign of future bone erosion—one study of 55 patients found that synovitis and bone edema are independent predictors of erosion. “Areas of bone edema will likely result in an erosion if the patient is not treated,” Dr. Gravallese said. “However, early therapy can prevent progression to erosion.”1

In a finding now well known, the inhibition of RANK ligand has been identified as a way of keeping osteoclast precursor cells from differentiating into the cells that destroy bone.2

“This is one mechanism by which osteoclasts could be inhibited—that is, by inhibiting their differentiation,” Dr. Gravallese said. “And it’s been shown that the RANKL antibody has a profound effect on bone turnover.”

One area that has been a puzzle, she said, is why lupus patients seem to be more protected from erosion than RA patients, but there have been inroads into understanding this as well. A study out of the University of Rochester examined the role of interferon-alpha in a lupus mouse model as this process unfolds, yielding results that could have a bearing on clinical practice.

“Over time, as the mouse developed the lupus phenoytpe, interferon-alpha was increasingly produced—and during the phases of interferon-alpha production, erosion was not seen, even with arthritis, due to interferon-alpha expression,” Dr. Gravallese said. “This research showed that what interferon-alpha does in this model is to divert the precursor cells to a myeloid dendritic cell at the expense of osteoclast precursors. This might be one important mechanism by which lupus patients are protected from erosion.”