New Anticoagulants: Pros and Cons

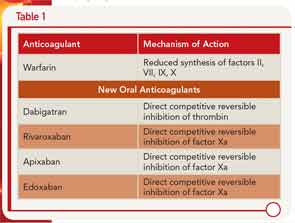

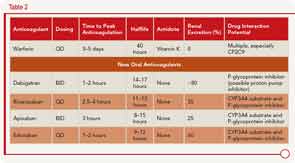

Dr. Kessler described the pharmacology of the new oral anticoagulants along with warfarin, including the different mechanisms of action (see Table 1) and clinical application (see Table 2).

A number of advantages and disadvantages should be weighed when considering use of one of these new anticoagulants over warfarin, he said. The advantages include lower rates of stroke and mortality, along with lower rates of intracerebral hemorrhage (although the rates of gastrointestingal bleeding are higher) compared to warfarin. One of the main advantages, he said, is that these anticoagulants are more convenient to use because they don’t require the type of regular monitoring that warfarin requires.

However, the lack of monitoring could also affect adherence adversely, he said. Other disadvantages of the new anticoagulants include the short half-life, which may not benefit patients with limited adherence, as well as the inability to titrate doses and the high cost of these drugs. One main disadvantage, he said, is that these new anticoagulants have no antidote. To address this, he cited a study by Kaatz et al. that provides some information and suggestions on reversal of three of the new anticoagulants, apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban.1 For example, oral activated charcoal can be used to reverse all three of these anticoagulants, whereas fresh frozen plasma will not be effective for any of these.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in St. Paul, Minn.

Coagulation Case Study

Patient description: A 35-year-old Caucasian female with a known longstanding history of systemic lupus erythematosis responsive to corticosteroids and without evidence of end organ failure presents with left lower extremity (LLE) asymmetric swelling and pain. Duplex Doppler ultrasounds confirm the presence of LLE proximal deep venous thrombosis (DVT) extending from the mid-calf to the mid–proximal thigh. Her SaO2 was 88% on room air; the CT pulmonary angiogram revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary emboli with low clot burden.

Laboratory data: Complete blood count: platelets=140,000/µL; 5,000 white blood count/absolute neutrophil count=12,000; hemoglobin/hematocrit=10.8/32; D-dimer=900 mcg (0-200); prothrombin time=12.5 seconds; activated partial thromboplastin time=32.5 seconds; fibrinogen=250 mg/dL. Complete metabolic profile revealed normal liver function tests and renal function.

Initial Management: The patient was treated with low–molecular weight heparin (LMWH), and her LLE swelling and pain resolved. She was discharged on Day 3 with overlapping LMWH and warfarin. On Day 9 postvenous thrombosis, she noted easy bruisability, persistent epistaxis, and now right lower extremity swelling and pain, associated with new onset of pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea. She returned to the ER and was diagnosed with a new pulmonary embolism and proximal DVT. Her blood pressure was 85/45, and pulmonary artery pressure on echo was 45 mm. Laboratory data: international normalized ratio was 1.3 on LMWH and warfarin bridging; platelets=10,000; hemoglobin/hematocrit=8.5/23.3; white blood count=12,000.